Emotional Intelligence 2.0 (19 page)

Read Emotional Intelligence 2.0 Online

Authors: Travis Bradberry,Jean Greaves,Patrick Lencioni

Federal economists pinpointed December 2007 as the start of the United States’ worst economy in 70 years, which means that 2008 did not see a single day

without

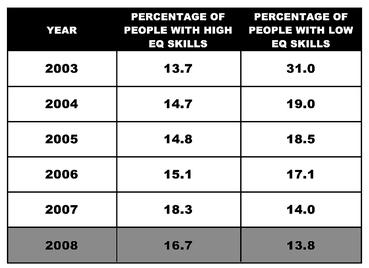

recession. The relapse in emotional intelligence skills between 2007 and 2008 is the product of economic woes. Hard times of any kind—financial, familial, or job-related—create more intense and often prolonged negative emotions that ultimately result in stress. In addition to the physical costs of stress, such as weight gain and heart disease, stress also taxes our mental resources. Under stress-free conditions, we can consciously devote extra effort to staying calm and collected during the trials and tribulations of everyday life. We are more confident in our abilities to handle unexpected events, and we allow our minds to overcome troublesome matters. Unmanaged stress, however, consumes much of those mental resources. It reduces our minds to something like a state of martial law in which emotions single-handedly dictate behavior, while our rational capacities are busy trying to turn lemons into lemonade. Suddenly, a little setback in your project at work that would have been no big deal in relatively prosperous times feels more like a catastrophe than a minor nuisance. For many people, their EQ skills desert them at precisely the time when they need these skills the most—under stress. Only those with well-trained and almost second-nature EQ skills can effectively weather the storm.

without

recession. The relapse in emotional intelligence skills between 2007 and 2008 is the product of economic woes. Hard times of any kind—financial, familial, or job-related—create more intense and often prolonged negative emotions that ultimately result in stress. In addition to the physical costs of stress, such as weight gain and heart disease, stress also taxes our mental resources. Under stress-free conditions, we can consciously devote extra effort to staying calm and collected during the trials and tribulations of everyday life. We are more confident in our abilities to handle unexpected events, and we allow our minds to overcome troublesome matters. Unmanaged stress, however, consumes much of those mental resources. It reduces our minds to something like a state of martial law in which emotions single-handedly dictate behavior, while our rational capacities are busy trying to turn lemons into lemonade. Suddenly, a little setback in your project at work that would have been no big deal in relatively prosperous times feels more like a catastrophe than a minor nuisance. For many people, their EQ skills desert them at precisely the time when they need these skills the most—under stress. Only those with well-trained and almost second-nature EQ skills can effectively weather the storm.

In other words, we lost 2.8 million highly skilled soldiers in the battle for a more emotionally intelligent society.

This stress seems to be having a significant impact on our collective emotional intelligence. We went from 18.3% of people being highly skilled in emotional intelligence in 2007 to only 16.7% in 2008. In other words, we lost 2.8 million highly skilled soldiers in the battle for a more emotionally intelligent society. That is 2.8 million people who could have been guideposts showing others the way to more emotionally intelligent behaviors, but are instead struggling to keep their own skills sharp.

Sheila began her career as a financial consultant specializing in healthcare at a multinational consulting firm. It only took a few years of dazzling clients and garnering rave reviews from upper management before she was eventually snatched up by her current employer—a large regional healthcare system in the Midwest. Still in her early 30s, Sheila is already an assistant vice president on the fast track to a C-level appointment. Her past and current superiors unanimously agree that Sheila is “smart,” yet there is something else—something they can’t quite put a finger on. Early in Sheila’s consulting career, after watching her defuse tense situations with clients time and again, her former manager summed up the secret to Sheila’s success: She just “

gets

people.”

gets

people.”

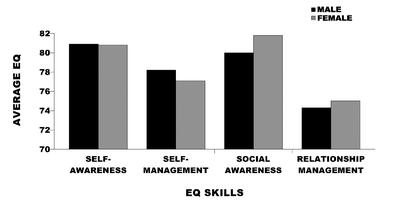

In 2003, we found some stark contrasts between the EQ skills expressed by men and those found in women like Sheila. Women outperformed men in self-management, social awareness, and relationship management. In fact, self-awareness was the only EQ skill in which men were able to keep pace with women.

But times have changed, and so have men.

As the graph shows, men and women are still neck and neck in their ability to recognize their own emotions—just as in 2003. But men have caught up in their ability to manage their own emotions. Chalk this change up to nothing more than shifting social norms.

This evolution of cultural mores benefits men. Men are now encouraged to pay their emotions some extra thought, which goes a long way toward clearer thinking. Not surprisingly, we found that a full 70% of male leaders who rank in the top 15% in decision-making skills also score the highest in emotional intelligence skills. In contrast, not one single male leader with low EQ was among the most skilled decision makers. Although this seems counterintuitive, it turns out that paying attention to your emotions is the most

logical

way to make good decisions. So instead of feeling like time spent addressing angst or frustration is somehow a sign of weakness, men are now free to get a stronger handle on their emotions in the name of sound judgment.

logical

way to make good decisions. So instead of feeling like time spent addressing angst or frustration is somehow a sign of weakness, men are now free to get a stronger handle on their emotions in the name of sound judgment.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN EQ

Considering the mountains of literature about EQ, you’d think corporate executives would be pretty smart about it. As we revealed in our

Harvard Business Review

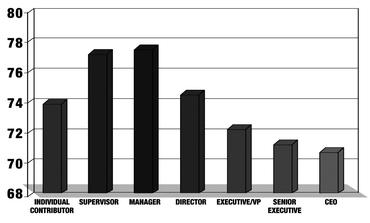

article, “Heartless Bosses,” our research shows that the message still is n’t getting through. We have measured EQ in half a million senior executives (including 1,000 CEOs), managers, and line employees across industries on six continents. Scores climb with titles, from the bottom of the corporate ladder upward toward middle management. Middle managers stand out, with the highest EQ scores in the workforce. But up beyond middle management, there is a steep downward trend in EQ scores. For the titles of director and above, scores descend faster than a snowboarder on a black diamond. CEOs, on average, have the lowest EQ scores in the workplace.

Harvard Business Review

article, “Heartless Bosses,” our research shows that the message still is n’t getting through. We have measured EQ in half a million senior executives (including 1,000 CEOs), managers, and line employees across industries on six continents. Scores climb with titles, from the bottom of the corporate ladder upward toward middle management. Middle managers stand out, with the highest EQ scores in the workforce. But up beyond middle management, there is a steep downward trend in EQ scores. For the titles of director and above, scores descend faster than a snowboarder on a black diamond. CEOs, on average, have the lowest EQ scores in the workplace.

CEOs, on average, have the lowest EQ scores in the workplace.

A leader’s primary function is to get work done through people. You might think, then, that the higher the position, the better the people skills. It appears the opposite is true. Too many leaders are promoted because of what they know or how long they have worked, rather than for their skill in managing others. Once they reach the top, they actually spend

less

time interacting with staff. Yet among executives, those with the highest EQ scores are the best performers. We’ve found that EQ skills are more important to job performance than any other leadership skill. The same holds true for every job title: those with the highest EQ scores within any position outperform their peers.

less

time interacting with staff. Yet among executives, those with the highest EQ scores are the best performers. We’ve found that EQ skills are more important to job performance than any other leadership skill. The same holds true for every job title: those with the highest EQ scores within any position outperform their peers.

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AND JOB TITLE

The mass exodus of Baby Boomers from the workplace has already begun. According to the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, between 2006 and 2010, Boomer retirement will have robbed American companies of nearly 290,000 f ull-time experienced employees.

Silver hair, pension funds, and personal memories of the Kennedy assassinations are not the only things our struggling economic engine will lose when Boomers settle into the quiet life. Boomers hold the majority of top leadership roles in the workplace, and their retirement creates a leadership gap that must be filled by the next generations. The question is whether or not the Boomers’ successors are up to the challenge.

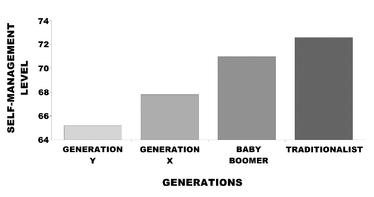

We wanted to find out. We broke EQ scores down into the four generations in today’s workplace—Generation Y (18-30 years old), Generation X (31-43 years old), Baby Boomers (43-61 years old), and Traditionalists (62-80 years old). When we looked at each of the four core EQ skills separately, a huge gap emerged between Boomers and Gen Y in self-management. In a nutshell, Baby Boomers are much less prone to fly off the handle when things don’t go their way than the younger generations.

It may not appear that this should create any real cause for concern. After all, retirement has been a fact of life ever since FDR signed the Social Security Act. The generation that designated Dennis Hopper as its unofficial spokesman proved capable of filling the superhuman-sized work boots of the Greatest Generation. So how hard can it be for the l eaders-in-waiting to replace the

Easy Rider

Generation?

Easy Rider

Generation?

Without well-honed self-management skills, it might be a lot harder than we think. Of course, while Gen Y’s approach may be

different

from the Boomers’ approach, many would argue that it isn’t any

worse

. Actually, when you consider how knowledgeable and technically proficient Gen Yers are, they might even have a leg up on their predecessors in the Information Age. However, it should be clear by now that there is a lot more to leadership than being a walking Wikipedia. So, if Gen Yers can’t manage themselves, how can we expect them to manage, much less lead, others?

different

from the Boomers’ approach, many would argue that it isn’t any

worse

. Actually, when you consider how knowledgeable and technically proficient Gen Yers are, they might even have a leg up on their predecessors in the Information Age. However, it should be clear by now that there is a lot more to leadership than being a walking Wikipedia. So, if Gen Yers can’t manage themselves, how can we expect them to manage, much less lead, others?

At TalentSmart

®

, we went round and round debating the possible explanations for this chasm in self-management skill between the experienced and youthful. One possibility seemed that coming of age with too many video games, instantaneous Internet gratification, and doting parents has created a generation of self-indulgent young workers who can’t help but wear their emotions on their sleeve in tense situations. However, we weren’t convinced.

®

, we went round and round debating the possible explanations for this chasm in self-management skill between the experienced and youthful. One possibility seemed that coming of age with too many video games, instantaneous Internet gratification, and doting parents has created a generation of self-indulgent young workers who can’t help but wear their emotions on their sleeve in tense situations. However, we weren’t convinced.

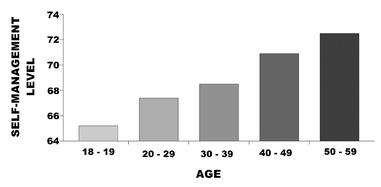

When we looked at the data from another angle, the picture became clearer. Self-management skills appear to increase steadily with age—60 year olds scored higher than 50 year olds, who scored higher than 40 year olds, and so on. That means the younger generation’s deficient self-management skills have little to do with things we can’t change like the effects of growing up in the age of iPods and MySpace. Instead, Gen Xers and Gen Yers just haven’t had as much life in which to practice managing their emotions. That’s good news, because practice is something Gen Yers can get. Reversing the hands of time to go back and change their upbringing might be tricky.

. . . the younger generation’s deficient self-management skills have little to do with

things we can’t change like the effects of growing up in the age of iPods and MySpace.

Other books

Indian Curry Recipes by Catherine Atkinson

La formación de América del Norte by Isaac Asimov

Liars All by Jo Bannister

Dream Magic: Awakenings by Harshaw, Dawn

The Chosen Dead (Jenny Cooper 5) by Hall, M. R.

Lord of Chaos by Robert Jordan

Out of My League by Michele Zurlo

The Honorable Heir by Laurie Alice Eakes

The Aurora (Aurora Saga, Book 1) by Adrian Fulcher

The Invention of Nature by Andrea Wulf