Emotional Intelligence 2.0 (18 page)

Read Emotional Intelligence 2.0 Online

Authors: Travis Bradberry,Jean Greaves,Patrick Lencioni

To do this, you need to let go of blame and focus on the repair. Do you want to be right, or do you want a resolution? Use your self-awareness skills to see what you are contributing to the situation; self-manage to put your tendencies aside and choose the high road. Your social awareness skills can help you identify what the other person brought to the table or feels. Looking at both sides will help you figure out where the interaction broke down, and which “fix-it” statement is needed to begin the repairs. Fix-it statements feel like a breath of fresh air, are neutral in tone, and find common ground. A “fix-it” statement can be as simple as saying, “This is hard,” or asking how the person is feeling. Most conversations can benefit from a fix-it, and it won’t do any harm if you feel the conversation breaking down.

Fix-it statements feel like a breath of fresh air, are neutral in tone, and find common ground.

This strategy will help you maintain open lines of communication when you’re upset, and with conscious effort and practice, you will be able to fix your broken conversations before they become damaged beyond repair.

“Why did I get passed over for the promotion?” your staff member Judith asks with a slightly defensive tone, a wounded posture, and a quivering voice. This is going to be a tough one. The news leaked out early about Roger’s promotion before you could speak with Judith. You value Judith and her work, but you’ll need to explain that she’s not ready for the next level yet. That’s not the hardest part of this conversation—damage control is another story.

From the boardroom to the break room, tough conversations will surface, and it is possible to calmly and effectively handle them. Tough conversations are inevitable; forget running from them because they’re sure to catch up to you. Though EQ skills can’t make these conversations disappear, acquiring some new skills can make these conversations a lot easier to navigate without ruining the relationship.

1.

Start with agreement.

If you know you are likely to end up in a disagreement, start your discussion with the common ground you share. Whether it’s simply agreeing that the discussion will be hard but important or agreeing on a shared goal, create a feeling of agreement. For example: “Judith, I first want you to know that I value you, and I’m sorry that you learned the news from someone other than me. I’d like to use this time to explain the situation, and anything else you’d like to hear from me. I’d also like to hear from you.”

2.

Ask the person to help you understand his or her side.

People want to be heard—if they don’t feel heard, frustration rises. Before frustration enters the picture, beat it to the punch and ask the person to share his or her point of view. Manage your own feelings as needed, but focus on understanding the other person’s view. In Judith’s case, this would sound like, “Judith, along the way I want to make sure you feel comfortable sharing what’s on your mind with me. I’d like to make sure I understand your perspective.” By asking for Judith’s input, you are showing that you care and have an interest in learning more about her. This is an opportunity to deepen and manage your relationship with Judith.

3.

Resist the urge to plan a “comeback” or a rebuttal.Your brain cannot listen well and prepare to speak at the same time. Use your self-management skills to silence your inner voice and direct your attention to the person in front of you. In this case, Judith has been passed up for a promotion that she was really interested in, and found out about it through the grapevine. Let’s face it—if you’d like to maintain the relationship, you need to be quiet, listen to her shock and disappointment, and resist the urge to defend yourself.

4.

Help the other person understand your side, too.Now it is your turn to help the other person understand your perspective. Describe your discomfort, your thoughts, your ideas, and the reasons behind your thought process. Communicate clearly and simply; don’t speak in circles or in code. In Judith’s case, what you say can ultimately be great feedback for her, which she deserves. To explain that Roger had more experience and was more suited for the job at this time is an appropriate message. Since his promotion was leaked to her in an unsavory way, this is something that requires an apology. This ability to explain your thoughts and directly address others in a compassionate way during a difficult situation is a key aspect of relationship management.

5.

Move the conversation forward.

Once you understand each other’s perspective, even if there’s disagreement, someone has to move things along. In the case of Judith, it’s you. Try to find some common ground again. When you’re talking to Judith, say something like, “Well, I’m so glad you came to me directly and that we had the opportunity to talk about it. I understand your position, and it sounds like you understand mine. I’m still invested in your development and would like to work with you on getting the experience you need. What are your thoughts?”

6.

Keep in touch.

The resolution to a tough conversation needs more attention even

after

you leave it, so check progress frequently, ask the other person if he or she is satisfied, and keep in touch as you move forward. You are half of what it takes to keep a relationship oiled and running smoothly. In regard to Judith, meeting with her regularly to talk about her career advancement and promotion potential would continue to show her that you care about her progress.

In the end, when you enter a tough conversation, prepare yourself to take the high road, not be defensive, and remain open by practicing the strategies above. Instead of losing ground with someone in a conversation like this, it can actually become a moment that solidifies your relationship going forward.

EPILOGUE

JUST THE FACTS: A LOOK AT THE LATEST DISCOVERIES IN EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE

W

hen TalentSmart

®

released the

Emotional Intelligence Appraisal

®

, EQ was still taking root in the minds of business leaders, other professionals, and anyone who simply wanted to lead a happier and healthier life. By measuring their EQ and showing them how to improve in one swoop, the

Emotional Intelligence Appraisal

®

quickly became the vehicle that enabled people to turn their newfound emotional mastery into strengthened relationships, better decisions, stronger leadership, and ultimately, more successful organizations. At TalentSmart

®

, we’ve watched hundreds of thousands of people from the top to the bottom of organizations take the journey to higher EQ.

hen TalentSmart

®

released the

Emotional Intelligence Appraisal

®

, EQ was still taking root in the minds of business leaders, other professionals, and anyone who simply wanted to lead a happier and healthier life. By measuring their EQ and showing them how to improve in one swoop, the

Emotional Intelligence Appraisal

®

quickly became the vehicle that enabled people to turn their newfound emotional mastery into strengthened relationships, better decisions, stronger leadership, and ultimately, more successful organizations. At TalentSmart

®

, we’ve watched hundreds of thousands of people from the top to the bottom of organizations take the journey to higher EQ.

The field of EQ skill development has truly blossomed since then, and we’ve taken special interest in tracking the changing landscape all along the way. What we’ve found in our studies has sometimes startled and often encouraged us. What remains constant throughout our discoveries is the vitally important role EQ skills play in the quest to lead a happy, healthy, and productive personal and professional life. More specifically, our research sheds new light on the battle of the sexes, the generational divide, the quest for career advancement and higher-paying jobs, as well as clueing us in on which countries are primed for future success in an increasingly global economy. All offer hope for those looking to increase their EQ skills.

Here’s what we found . . .

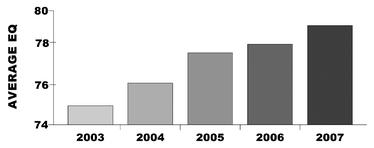

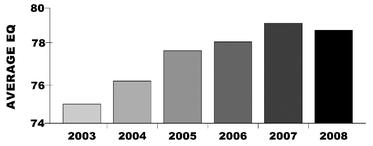

The Poles Are Melting: EQ Then and NowAt the end of 2008, we took a good look at how the collective EQ of the U.S. population had changed since 2003. While we weren’t surprised to see those we tested and taught improve their EQ, we were intrigued to watch the EQ scores of newbies increase with each passing year. And the increase continued, year after year after year—the EQ scores of those we’d never tested or taught made a slow and steady climb. We discovered a substantial increase in the emotional intelligence of the U.S. workforce between 2003 and 2007.

Skeptics might be tempted to look at the graph and think,

What’s the big deal? That’s just a four-point increase in

five years!

But think of the impact a seemingly small temperature increase—say one or two degrees—has upon our ecosystem. The same is true with human behavior in the workplace, where the frozen poles of low emotional intelligence are starting to melt.

What’s the big deal? That’s just a four-point increase in

five years!

But think of the impact a seemingly small temperature increase—say one or two degrees—has upon our ecosystem. The same is true with human behavior in the workplace, where the frozen poles of low emotional intelligence are starting to melt.

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE

Once we take a closer look at the specific changes the broad gains in EQ have created, the real power of the transformation comes to light. In the last five years, we’ve seen the percentage of people who are highly attuned to their own emotions and to the emotions of other people rise from 13.7% to 18.3%. During that same period, the percentage of people with a poor understanding of how anxiety, frustration, and anger influence their behavior has dropped from 31.0% to 14.0%. When you apply these proportions to the 180 million people in America’s workforce, it means that 9 million more people today than in 2003 almost always keep their cool during heated conflicts; 9 million more people actually show that they care about their co-workers and customers when they suffer hard times; and 25 million fewer people are painfully oblivious to the impact their behavior has on others.

What makes this discovery so special is that prior to taking the test, very few, if any, of the people in our sample had ever received formal emotional intelligence training. Yet their average EQ scores steadily increased from year to year. It’s as if the people who intentionally practice emotionally intelligent behaviors are infecting others who may have never even heard of the concept. Emotional intelligence skills—much like emotions themselves—are contagious. That means that our EQ skills are highly dependent on the surrounding people and circumstances. The more we interact with empathetic people, the more empathetic we become. The more time we spend with other people who openly discuss emotions, the more skilled we become at identifying and understanding emotions. That is precisely what makes emotional intelligence a learned skill, rather than some unalterable trait bestowed only upon a lucky few at birth.

But that’s where the good times end. In 2008—for the first time since we began tracking it—collective emotional intelligence dropped, underscoring just how susceptible to change these skills truly are.

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE

Other books

Just One Night, Part 1: The Stranger by Davis, Kyra

Highfall by Alexander, Ani

Rio's Fire by Lynn Hagen

Knock on Wood by Linda O. Johnston

Gay Phoenix by Michael Innes

The Gay Icon Classics of the World by Robert Joseph Greene

Patrimony by Alan Dean Foster

Venice Nights by Ava Claire

John Wayne: The Life and Legend by Scott Eyman

Seducing Sophie by Juliette Jaye