CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition (59 page)

Read CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition Online

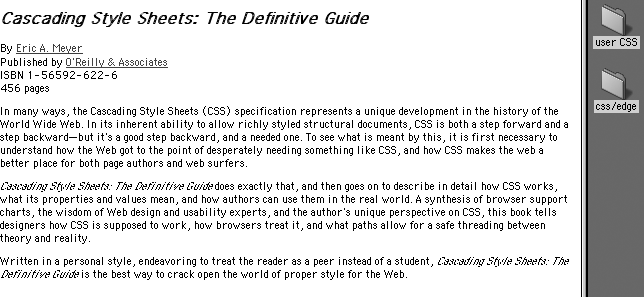

Authors: Eric A. Meyer

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Web / Page Design

Even though list styling isn't as sophisticated as we might like, and browser support

for generated content is somewhat spotty (as of this writing, anyway), the ability to

style lists is still highly useful. One relatively common use is to take a list of

links, remove the markers and indentation, and thus create a navigation sidebar. The

combination of simple markup and flexible layout is difficult to resist. With the

anticipated enhancements to list styling in CSS3, I expect that lists will become more

and more useful.

For now, in situations where a markup language doesn't have intrinsic list elements,

generated content can be an enormous help—say, for inserting content such as icons to

point to certain types of links (PDF files, Word documents, or even just links to

another web site). Generated content also makes it easy to print out link URLs, and its

ability to insert and format quotation marks leads to true typographic joy. It's safe to

say that the usefulness of generated content is limited only by your imagination. Even

better, thanks to counters, you can now associate ordering information to elements that

are not typically lists, such as headings or code blocks. Now, if you want to support

such features with design that mimics the appearance of the user's operating system,

read on. The next chapter will discuss ways to use system colors and fonts in CSS

design.

The vast majority of CSS is concerned with styling documents, but it offers a passel of

useful interface-styling tools for more than just documents. For example, Mozilla's

developers created its browser's interface (and that of many Mozilla clones) using a

language called XUL. XUL employs CSS and CSS-like declarations to present the navigation

buttons, sidebar tabs, dialog boxes, status boxes, and other pieces of the chrome itself.

Similarly, you can reuse aspects of the user's default environment to style a document's

fonts and colors; it's even possible to exert influence over focus highlighting and the

mouse cursor. CSS2's interface capabilities can make the user's experience more

enjoyable—or more confusing, if you aren't careful.

There may be times when you want your document to mimic

the user's computing environment as closely as possible. An obvious example is if you're

creating web-based applications, where the goal is to make the web component seem like a

part of the user's operating system. While CSS2 doesn't make it possible to reuse every

last aspect of the operating system's appearance in your documents, you can choose from

a wide variety of colors and a short list of fonts.

Let's say you've created an element that functions as a

button (via JavaScript, for example). By making the control look just like a button

in the user's computing environment, you meet the user's expectations of how a

control should look and thus make it more usable.

To accomplish the given example, simply write a rule like this:

a.widget {font: caption;}

This will set the font of anyaelement with aclassofwidgetto use the same font family, size, weight, style, and variant as

the text found in captioned controls, such as a button.

CSS2 defines six system font keywords. These are described in the following list:

captionThe font styles used for captioned controls, such as buttons and

drop-downsiconThe font styles used to label operating system icons, such as hard

drives, folders, and filesmenuThe font styles used for text in drop-down menus and menu lists

message-boxThe font styles used to present text in dialog boxes

small-captionThe font styles used for labeling small captioned controls

status-barThe font styles used for text in window status bars

It's important to realize that these values can be used only with thefontproperty and are their own form of shorthand. For

example, let's assume that a user's operating system shows icon labels as 10-pixel

Geneva with no boldfacing, italicizing, or small-caps effects. This means that the

following three rules are all equivalent, and have the result shown in

Figure 13-1

:

body {font: icon;}

body {font: 10px Geneva;}

body {

font-weight: normal;

font-style: normal;

font-variant: normal;

font-size: 10px;

font-family: Geneva;

}

Figure 13-1. Making text look like an icon label

So a simple value likeiconactually embodies a

whole lot of other values. This is fairly unique in CSS, and it makes working with

these values just a little more complex than usual.

As an example, suppose you want to use the same font styling as icon labels, but

you want the font to be boldfaced even if icon labels are not boldfaced on a user's

system. You'd need a rule with the declarations in the order shown:

body {font: icon; font-weight: bold;}

By writing the declarations in this order, you cause the user agent to set thebodyelement's font to match icon labels with

the first declaration, and then modify the weight of that font with the second. If

the order were reversed, then thefontdeclaration's value would override thefont-weightvalue from the second declaration, and the boldfacing would be lost. This is similar

to the way shorthand properties (likefontitself)

must be handled.

You may be wondering about the lack of a generic font family, since it's usually

recommended that the author write something likeGeneva,sans-serif;(in case a user's

browser doesn't support the specified font). CSS won't let you "tack on" a generic

font family, but in this case, it isn't needed. If the user agent manages to extract

the font family used to display something in the computing environment, then it's a

pretty safe bet the same font is available for the browser to use.

If the requested system font style is not available or can't be determined, the

user agent is allowed to guess at an appropriate set of font styles. For example,small-captionmight be approximated by taking

the styles forcaptionand reducing the font's

size. If no such guess can be made, the user agent should use a "user agent default

font" instead.

As of this writing, the working draft of the CSS3 Color module deprecates the

system color keywords in favor of the new propertyappearance. Similarly, CSS2.1 deprecates these keywords in

anticipation of changes in CSS3. Authors are strongly encouraged not to use the

system colors, as they are not likely to appear in future versions of CSS. This

information is included because some currently available browsers do support

system colors.

If you want to reuse the colors specified in the user's operating system, CSS2

defines a series of system color keywords. These are values that can be used in any

circumstance where a

allowed. For example, you could match the background of an element with the user's

desktop color by declaring:

div#test {background-color: Background;}

Thus, for example, you could give a document the system's default text and

background color like this:

body {color: WindowText; background: Window;}

Such customization increases the odds that the user will be able to read the

document, since he has presumably configured his operating system to be usable. (If

not, he deserves whatever he gets!)

There are 28 system color keywords in total, although CSS does not explicitly

define them. Instead, there are some generic (and very short) descriptions of each

keyword's meaning. The following list describes all 28 keywords. In cases where there

is a direct analog with the options in the "Appearance" tab of the Display control

panel in Windows 2000, it is noted parenthetically after the description.

ActiveBorderThe color applied to the outside border of an active window (the first

color in "Active Windows Border").ActiveCaptionThe background color of the caption of the currently active window (the

first color in "Active Title Bar").AppWorkspaceThe background color used in an application that allows multiple

documents— e.g., the background color "behind" the open documents in

Microsoft Word (the first color in "Application Background").BackgroundThe background color for the desktop (the first color in

"Desktop").ButtonFaceThe color used on the "face" of a three-dimensional button.

ButtonHighlightThe highlight color found on the edges of three-dimensional display

elements that face away from the virtual light source. Thus, if the virtual

light source is located in the upper left, this would be the highlight color

used on the right and bottom edges of the display element.ButtonShadowThe shadow color for three-dimensional display elements.

ButtonTextThe color of text found on push buttons (the font color in "3D

Objects").CaptionTextThe color of text found in captions, the size box, and the symbol in a

scrollbar arrow box (the font color in "Active Title Bar").GrayTextThe grayed (disabled) text. This keyword is interpreted as

#000if the current display driver does not

support a solid gray color.HighlightThe color of item(s) selected in a control (the first color in "Selected

Items").HighlightTextThe text color of item(s) selected in a control (the font color in

"Selected Items").InactiveBorderThe color applied to the outside border of an inactive window (the first

color in "Inactive Window Border").InactiveCaptionThe background color of the caption of an inactive window (the first

color in "Inactive Title Bar").InactiveCaptionTextThe color of text in an inactive caption (the font color in "Inactive

Title Bar").InfoBackgroundThe background color in tool tips (the first color in "ToolTip").

InfoTextThe text color in tool tips (the font color in "ToolTip").

MenuThe color of a menu's background (the first color in "Menu").

MenuTextThe color of text found in menus (the font color in "Menu").

ScrollbarThe "gray area" of a scrollbar.

ThreeDDarkShadowThe same color as a dark shadow found on three-dimensional display

elements.ThreeDFaceThe same color as the face of three-dimensional display elements.

ThreeDHighlightThe color of highlights found on three-dimensional display

elements.ThreeDLightShadowThe light color found on three-dimensional display elements (for edges

facing the light source).ThreeDShadowThe dark shadow found on three-dimensional display elements.

WindowThe color in the background of a window (the first color in

"Window").WindowFrameThe color applied to the frame of a window.

WindowTextThe color of text in windows (the font color in "Window").

CSS2 defines the system color keywords to be case-insensitive but recommends using

the mixed capitalization shown in the previous list, which makes the color names more

readable. As you can see,ThreeDLightShadowis

easier to understand at a glance thanthreedlightshadow.

An obvious drawback of the vague nature of the system color keywords is that

different user agents may interpret the keywords in different ways, even if the user

agents are running in the same operating system. Therefore, don't rely absolutely on

consistent results when using these keywords. For example, avoid text that reads,

"Look for the text whose color matches your desktop", since the user may have placed

a desktop graphic (or "wallpaper") over the default desktop color.