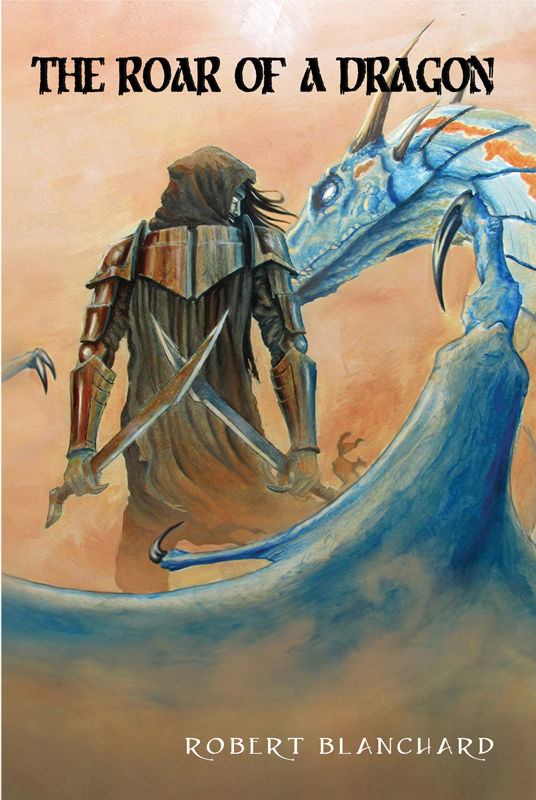

The Roar of a Dragon

Read The Roar of a Dragon Online

Authors: Robert Blanchard

THE ROAR OF A DRAGON

ROBERT BLANCHARD

Text copyright © Robert Blanchard 2016

Artwork copyright © Max Cartwright 2016

Map copyright © Hannah Purkiss 2016

All rights reserved.

Robert Blanchard has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is a work of fiction. Names and characters are the product of the author’s imagination and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by electronic, mechanical or any other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publisher and Author. You must not circulate this book in any format.

This e-book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This e-book may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, or you were not provided with a review copy by the Publisher or Author only, then please return to

rowanvalebooks.com

or our online distributors and purchase your own copy, as well as informing us of a potential breach of copyright. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

First published 2016

by Rowanvale Books Ltd

Imperial House

Trade Street Lane

Cardiff

CF10 5DT

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBNs:

978-1-910607-68-8 (epub)

978-1-910607-69-5 (mobi)

978-1-910607-70-1 (pdf)

There are so many people to whom this project belongs to; I doubt I can fit it all in one page, but I’ll try anyway.

To my two boys, Christian and Aidan. It’s true that without me, you wouldn’t be here, but it’s also true that without you two, I wouldn’t be here either. I most certainly would not be the man I have become. You gave my life a purpose and meaning. I love both of you with all of my heart.

To Devin, Sarah Jean, and all of my other “kids.” It means a great deal when kids who aren’t yours biologically still consider you to be a father figure. It means I must be doing something right. Love you guys!

To Dad. You have helped me out so much over the years that I could never possibly pay you back. Yet you’ve never once complained, or shown one bit of annoyance or petulance. You stood by your word to help me as much as you could when I asked, and I will never forget that.

To Mom. I know that no matter what, you did the best you could.

To Kate and Dawn. Your great advice and blunt honesty is the engine behind this entire project. Thank you for your support and for showing me how important it is to understand constructive criticism.

To Lisa and Teresa. Your love and support have always meant a lot to me.

To Nichele and Jordin. Nichele, you are the best mother I know and I love Jordin like my own. To Jordin, I love you, Peanut Face!

To the CLC. You know who you are.

To Cat Charlton and her staff at Rowanvale Books. Thank you for giving me this amazing opportunity!

The wisest of our world say that our destinies are predetermined.

Fate is very deceptive; more often than not, it is never what anyone envisions it to be. Men will often boast about what their destiny is going to be, as if such a thing could be controlled — like, say, the amount of milk you want with your breakfast. They usually have very clear visions of their fate, and in some very rare cases, they succeed in shaping it exactly as they planned. But more commonly, fate often throws you many strange — and sometimes twisted — obstacles before revealing that your destiny is

not at all

what you thought it was going to be.

I would have preferred if fate had just told me straight out; it would have saved me a lot of trouble.

My name is Aidan, and I was born in the year 185 of the Fifth Age, in the village of Dura, kingdom of Delmar. Though there are several mighty kingdoms in our world, Delmar is the heart of it all, in more ways than one; not only is it considered to be the most prestigious country, it is also literally in the heart of the land, which makes it a center for tourism and trade. Its White Army is the largest, and is generally considered to be the most fearsome.

As I was born, my mother died, leaving my father to raise me alone on the family farm. In my later years, I would see many children who were resented — even blamed — for the death of their mothers as a result of their birth. I can happily say, however, that my father was not such a person — he saw me as the last piece of my mother that still survived. Because of that, I can say without hesitation that my childhood was blessed.

To this day, I have no idea how my father took care of me and his work on the farm at the same time. Sometimes I laughingly think to myself that perhaps he just plopped me in a little wagon and brought me out onto the field, where he tended to the animals, the crops, and me, as needed.

Come to think of it, that may be

exactly

how he did it.

See, my father could be pretty stern, but he also had a goofy sense of humor at times, and that made my childhood pretty interesting. That was a good thing, too, because we usually kept to ourselves on the farm — the only time we saw people is when we traveled into town to trade or sell our goods, which occurred about once a month, starting in the fall until the end of the year. As a result, meeting new people was somewhat difficult for me at first; I was definitely on the shy side.

Another thing I struggled with was sleeping. Dreams about the mother I’d never met plagued me constantly. When I was younger, the dreams would hurt me very deeply. Later, I would be upset for a while and then read a book until I could fall back asleep.

You might be asking yourself how a farmer with very little gold could afford to purchase books. We couldn’t — but my father had an older brother in a nearby town who owned a bookstore. My uncle was a very nice man: rotund, cheerful, and very much had the same sense of humor as my father — only he showed it a lot more. We visited him every once in a while, and my uncle was more than happy to allow us to read any books in his store for as long as we wanted. My father loved to read, and it wasn’t long before I shared that same passion. While my father read tantalizing fiction stories, I read children’s books.

At about four years of age, I tried to help my father out on the farm (emphasis on

tried)

. I remember once that when we were out in the field picking carrots, I started to pull some with him — until he stopped me and pointed out that the ones I had yanked out of the ground were not ripe yet. He smiled and tousled my hair, then began to show me which ones were good to pull. I always enjoyed those early times on the farm, just me and my father as he showed me the way of farm life. Naturally, I struggled at first, as I soon figured out that farm life is much more difficult than it seems. But my father was patient, and he really seemed to enjoy the fact that his son was trying to help him — even if I did cost him a few crops.

But even at that young age, something inside me told me that the farm wasn’t where I belonged…

BOOK 1

‘Destiny has two ways of crushing us…by refusing our wishes…and by fulfilling them.’

Henri Frederic Amiel

‘Oh, come on, you stupid cow!’

She’d knocked over the bucket. Again.

Sighing in exasperation, I stood up from the stool I had placed next to the cow so that I could milk her. She had a tendency to do this every once in a while — get irritated that I was pulling on her udders (now that I say it like that, I would be irritated too) and knock over the bucket with her rear legs, sending its contents spilling all over the hay-covered ground. It was beyond frustrating — I balled my hands into fists and leaned against one of the nearby wooden poles that supported the barn.

Still, it wasn’t in me to be mean for no real reason, especially to an animal. Especially these animals, since they were the only company I had.

‘I’m sorry, girl,’ I said, walking up to her and rubbing the side of her head. ‘I’m just not having a good day, I guess.’

The cow continued to chomp on some hay, giving no indication that she had understood or cared.

I didn’t have any real understanding of what a ‘good’ day was. I mean, life wasn’t so bad, but it was very hard work, especially for someone like me — a sixteen-year-old running the family farm by himself. Saying that, I was pretty used to it by now; I’d been doing it for the last two years, after all.

Before then, it had been just me and my father, Uaine. I loved my dad. He took care of me, taught me the ways of life, and at least

tried

to make sure I stayed on the right path. I say ‘tried’ because I certainly didn’t make it easy for him. My thoughts drifted to simpler times, both happy and difficult, settling on a specific memory from when I was seven…

I was transported back to the living room, staring wistfully at a particular statuette that sat on an end table, molded into the shape of a cat.

‘You okay, Aidan?’ Father asked, snapping me out of my daydreaming. He usually called me ‘boy’ or ‘son’, and he only called me by my name when he was serious.

‘Yes, Father,’ I said quietly as I turned my head to look at him.

My father was unconvinced, but it was too early in the morning to reassure him. ‘Have you had any dreams lately?’ he asked gently.

I lowered my eyes for a moment, then returned my gaze to him. ‘Not in a couple of days.’

Father’s eyes narrowed a little. ‘You never said anything.’

I shrugged my small shoulders. When I first started having the dreams, I would wake up in tears, screaming for my mother. Now, a couple of years later, I would just get a little upset, and sleep or not sleep as my mind allowed. However, this was the first time that I hadn’t told Father about a dream that I’d had about her.

‘They don’t bother me anymore,’ I said, trying to sound convincing.

Father’s eyes narrowed further. ‘Do not lie to me, Aidan.’

I sighed. I’d known that he wouldn’t believe me when I’d said that, but I’d tried anyway. ‘I’m sorry, Father. I just… I know how much it hurts you too.’

I could almost see my father’s heart dropping to his stomach. He tried to find something to say in response, then gave it up for the moment and went to get my breakfast.

My stomach rumbled, bringing me back to reality.

‘Oh, hush,’ I growled back. ‘You should be used to this by now.’ After all, I’d barely been eating for the past year, due to my lack of ability to grow food as well as lack of coin to buy any.

I was still standing next to the cow. ‘I don’t suppose you’d want to cooperate this time, huh? Please?’

Still, the cow gave no evidence that she even knew I was there.

I set the bucket back up underneath the cow and sat back down on the stool. I tried to grab hold of one of the teats, but as soon as I did, the cow moved away from me. She was tied to a nearby pole, but had just enough rope to make things difficult.

‘Fine,’ I muttered, now utterly (no pun intended) discouraged. ‘Have it your way.’

I stood up (knocking over the stool as I did so) and stormed out the large double doors of the barn.

Just as I reached for the doors to push them open, my gaze fell to the far corner of the barn. Everything was back there, beckoning me.

No, no, no… you have work to do

.

Too true. I willed myself out of the barn and crossed in front of my small cottage home, which my father had built for my mother, and headed out to the fields to the right. I was almost at the well next to the house when I realised I had left the cow tied to the post.

‘Oh, well… serves her right.’ She could live without hay and water for a couple hours… stupid cow.

I drank some water from the well, then headed out to the fields to continue harrowing them. The weather had been perfect for the season — a few rain showers here and there, but no downpours that flooded the fields. A stark contrast to the previous year; the harvest hadn’t gone very well, and I had to struggle to get through the winter. It had taken all the food that I had in the stores, the nuts I had collected and animals I had slaughtered to survive. I always hated slaughtering animals that I’d raised from calf and chick, but in the farming world, it was a necessary evil.

I could only hope for some luck from the harvest this year; being hungry had become an ever-constant annoyance.

Two donkeys waited patiently in the field, strapped to what appeared to be a giant garden rake used to harrow the fields. I made sure the wooden spikes were firmly entrenched in the soil, then grabbed the soft leather straps so that I could urge the donkeys forward.

‘Ya!’ I called, snapping the leather straps against their backs. ‘Go!’

Two donkeys strapped to the harrow… and neither one of them even

twitched

.

I heaved a sigh. ‘Really, guys? C’mon… it’s a beautiful day, you’ve been well fed. What else do you really need?’ I accompanied this pep talk with a light stroking to the ears of each animal, which both responded to favorably.

‘Alright,’ I said, grabbing the strap again and feeling more confident. ‘Let’s go!’ I yelled, cracking the strap once again.

Nothing.

Now I was really frustrated. ‘Ah, what the heck, guys? Eating’s not very important, is it?’

Finally, one of the donkeys responded. He tossed his head back happily and sighed contentedly.

I’d had enough. That dark corner of the barn was now beckoning with even more persistence. Apparently, the gods had different plans for me that didn’t involve farming… or eating.

Before I knew it, I was back in the barn. The cow was less than thrilled at being left tied to the post, so I untied her and led her back out to the fields behind the barn. Once I was back inside, however, it was time for me to indulge those feelings that were insistently dragging me toward what I truly loved.

Father said I was crazy. Perhaps he was right. When I was younger, I believed that my destiny did not lay on a farm — it lay on a battlefield. It happened innocently enough; my uncle, Hagan, owned a bookstore in the nearby city of Kiver, which lay in the north. It was there that my father and I traded our goods. Just like my father, I loved to read, and one day while we were visiting, Father asked me to grab a book and go upstairs. The book I grabbed off-handedly was titled

Hero Knights of the Second Age

.

My life would never be the same.

From that point on, I was forever drawn to the military lifestyle and to the glory of being a knight. Father lectured me sternly, especially as I started to stray from my duties on the farm. He told me that farmers didn’t become knights, and that I should accept what fate had dealt me. He wasn’t trying to put me down or hurt me, simply trying to be realistic. Over time, I slowly came to realize that he was right, especially as I entered my adolescent years.

After my father and uncle died (within a month of each other), I was suddenly alone in the world at the age of fourteen. My entire focus fell to my work on the farm. This was partly due to the need to survive, but more importantly it was a way to deal with my losses and the cold, harsh feeling of loneliness. And after two years, my work ethic, instilled by my father, was now firmly ingrained.

But my fascination with knighthood still lingered.

Although I loved my father and missed him dearly, I took advantage of his absence to build a couple of dummies out of wood and straw — something he would never have allowed me to do. The dummies were quite crude, and probably a little dangerous, to be honest. I followed that horrible and laughable attempt at carpentry with another one, creating a rudimentary wooden sword that gave me splinters in my hands every time I used it. But every morning and every night (or during times like this, when I was extremely irritated), I would venture to my practice area, and I would continue my exhibition in ‘swordplay.’

I wasn’t taking my dreams of knighthood very seriously anymore, but sometimes fate has a way of changing your future in one moment…