Closing the Ring (86 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

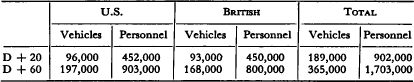

He was followed by several Naval, Army, and Air Commanders, and also by the Principal Administrative Officer, who dwelt upon the elaborate preparations that had been made for the administration of the force when it got ashore. The amount of paraphernalia sounded staggering, and reminded me of Admiral Andrew Cunningham’s story of the dental chairs being landed at Algiers in the first flight of Operation “Torch.” I was told, for example, that two thousand officers and clerks were being taken across the sea to keep records, and I was given the following statement, which showed that twenty days after the landing—D+20—there would be one vehicle ashore for every 4.77 men. Each vehicle required a driver and its share of maintenance staff.

Plus replacement of casualties.

Although these figures included fighting vehicles, such as guns, armoured cars, and tanks, I remembered too well the swarm in the Anzio beachhead, and after reflection I asked Ismay to write to Montgomery and express my concern about

what seemed to me an excess of motor-cars and non-fighting vehicles of all kinds. This he did, and we arranged to discuss it when I visited the General’s Headquarters on Friday, May 19. This interview has been misrepresented. Montgomery is said to have led me into his study and advised me not to speak to his Staff, and to have threatened to resign if I insisted on altering the loading plans at the eleventh hour, and I am alleged to have given way, and, after telling his officers that I was not allowed to talk to them, to have walked out. It may be well therefore to state what actually happened.

When I arrived for dinner, Montgomery asked to speak to me alone, and I went into his room. I do not remember the actual course of the conversation, but no doubt he explained the difficulties of altering the loading scale at this stage, seventeen days before D-Day. I am sure however that at no time, either in this conversation or in any other of the many I had with him during the war, did he threaten to resign, and that nothing in the nature of a confrontation with his Staff took place. I should not have accepted such behaviour. After our talk we went to dinner, at which only eight or nine persons, mostly the General’s personal staff, were present. All our proceedings were of a most friendly character, and when that night the General asked me to put something for him in his private book, as I had done before other great battles, I wrote the following, which has already been published elsewhere: “On the verge of the greatest adventure with which these pages have dealt, I record my confidence that all will be well, and that the organisation and equipment of the Army will be worthy of the valour of the soldiers and the genius of their chief.”

I may add however that I still consider that the proportion of transport vehicles to fighting men in the early phase of the cross-Channel invasion was too high and that the operation suffered both in risk and execution from this fact.

* * * * *

Another project was close to my heart. Our aim was to liberate France, and it seemed both desirable and fitting that a

French division should be landed early in the operation and the French people told that their troops were fighting once more on the soil of France. The 2d French Armoured Division, commanded by General Leclerc, had had a long and distinguished career in North Africa, and as early as March 10, I had told de Gaulle that I hoped they would be with us in the main battle. Since then the matter had been much probed by the Chiefs of Staff. Eisenhower was glad to have the division, and General Wilson did not plan to use it in the attack on the Riviera. The problem was how to get it home and properly mounted in time. The troops could be shifted easily enough, but there was little room in home-coming ships for their equipment and their vehicles. After correspondence between the British and United States Chiefs of Staff and Allied Headquarters in Algiers, much had been transported in the landing-ships which were sailing back from the Mediterranean. But on April 4, the Chiefs of Staff reported that they would still be short of about two thousand vehicles. To give them British ones would seriously complicate Eisenhower’s problems of maintenance, and a few days later his Headquarters declared that no American ones could be provided either from the United Kingdom or the United States. This meant that the division would not be able to fight until long after the landing, all for the lack of comparatively few vehicles out of the immense numbers to be employed. Mr. Eden shared my disappointment, and on May 2, I made a personal appeal by letter to General Eisenhower.

Prime Minister to General Eisenhower

2 May 44

Please provide from your vast masses of transport the few vehicles required for the Leclerc division, which may give real significance to French re-entry into France. Let me remind you of the figures of Anzio—viz., 125,000 men with 23,000 vehicles, all so painfully landed to carry them, and they only got twelve miles.

Forgive me for making this appeal, which I know you will weigh carefully and probe deeply before rejecting.

His answer was reassuring.

General Eisenhower to Prime Minister

10 May 44

I have gone very carefully into the transportation status of the Leclerc division, and members of my Staff have conferred with General Leclerc on the same subject.

I find that about eighteen hundred vehicles of the division, including nearly all the track and armoured vehicles, have already arrived here, or will arrive by May 15. Approximately twenty-four hundred vehicles remain to be shipped, and on the present schedule all but four hundred of these vehicles should be in England by June 12, the remainder reaching here by June 22. General Leclerc says that he now has adequate material for training, and he is being assisted by the American Third Army, to which he is attached. His general supply situation is good, and the minor deficiencies which remain after his vehicles arrive, including provision for maintenance, will be met from American sources. I believe that the shipping and equipment schedule of the division will ensure their being properly provided prior to their entry into combat.

Thus all was arranged, and the march which had begun at Lake Chad ended through Paris at Berchtesgaden.

* * * * *

As D-Day approached, the tension grew. There was still no sign that the enemy had penetrated our secrets. He had scored a minor success at the end of April by sinking two American L.S.T.s which had been taking part in an exercise, but apparently he did not connect this with our invasion plans. We observed some reinforcement of light naval forces at Cherbourg and Havre during May, and there was more mine-laying activity in the Channel, but in general he remained quiescent, awaiting a definite lead regarding our intentions.

Events now began to move swiftly and smoothly to the climax. After the conference on May 15, His Majesty had visited each of the assault forces at their ports of assembly. On May 28, subordinate commanders were informed that D-Day would be June 5. From this moment all personnel committed to the assault were “sealed” in their ships or at their

camps and assembly points ashore. All mail was impounded and private messages of all kinds forbidden except in case of personal emergency. On June 1, Admiral Ramsay assumed control of operations in the Channel, the functions of the naval Commanders-in-Chief in the home ports being subordinated to his requirements.

I thought it would not be wrong for me to watch the preliminary bombardment in this historic battle from one of our cruiser squadrons, and I asked Admiral Ramsay to make a plan. He arranged for me to embark in H.M.S.

Belfast

, in the late afternoon of the day before D-Day. She would call in at Weymouth Bay on her passage from the Clyde, and would then rejoin her squadron at full speed. She was one of the bombarding ships attached to the centre British force, and I would spend the night in her and watch the dawn attack. I was then to make a short tour of the beaches, with due regard to the unswept mine areas, and come back in a destroyer which would have completed her bombardment and was to return to England for more ammunition.

Admiral Ramsay felt it his duty however to tell the Supreme Commander of what was in the air. Eisenhower protested against my running such risks. As Supreme Commander he could not bear the responsibility. I sent him word, as he has described, that while we accepted him as Supreme Commander of the British forces involved, which in the case of the Navy were four to one compared with those of the United States, we did not in any way admit his right to regulate the complements of the British ships in the Royal Navy. He accepted this undoubted fact, but dwelt on the addition this would impose upon his anxieties. This appeared to be both out of proportion to the scale of events and to our relations. I too had responsibilities, and felt I must be my own judge of my movements. The matter was settled accordingly.

However, a complication occurred which I have His Majesty’s permission to recount. When I attended my weekly luncheon with the King on the Tuesday before D-Day (May 30), His

Majesty asked me where I intended to be on D-Day. I replied that I proposed to witness the bombardment from one of the cruiser squadrons. His Majesty immediately said he would like to come too. He had not been under fire except in air raids since the Battle of Jutland, and eagerly welcomed the prospect of renewing the experiences of his youth. I thought about this carefully, and was not unwilling to submit the matter to the Cabinet. It was agreed to discuss the matter with Admiral Ramsay first.

Meanwhile, the King came to the conclusion that neither he nor I ought to go. He was greatly disappointed, and wrote me the following letter:

B

UCKINGHAM

P

ALACE

May

31, 1944

My dear Winston,

I have been thinking a great deal of our conversation yesterday, and I have come to the conclusion that it would not be right for either you or I to be where we planned to be on D-Day. I don’t think I need emphasise what it would mean to me personally, and to the whole Allied cause, if at this juncture a chance bomb, torpedo, or even a mine, should remove you from the scene; equally a change of Sovereign at this moment would be a serious matter for the country and Empire. We should both, I know, love to be there, but in all seriousness I would ask you to reconsider your plan. Our presence, I feel, would be an embarrassment to those responsible for fighting the ship or ships in which we were, despite anything we might say to them.

So, as I said, I have very reluctantly come to the conclusion that the right thing to do is what normally falls to those at the top on such occasions, namely, to remain at home and wait. I hope very much that you will see it in this light too. The anxiety of these coming days would be very greatly increased for me if I thought that, in addition to everything else, there was a risk, however remote, of my losing your help and guidance.

Believe me,

Yours very sincerely.

G

EORGE

R.I.

And later:

B

UCKINGHAM

P

ALACE

May

31, 1944

My dear Winston,

I hope you will not send me a reply to my letter, as I shall be seeing you tomorrow afternoon, when you can then give me your reactions to it before we see Ramsay.

I am,

Yours very sincerely,

G

EORGE

R.I

* * * * *

At 3.15

P.M

. on June 1, the King, with Sir Alan Lascelles in attendance, came to the Map Room at the Annexe, where I with Admiral Ramsay awaited him. The Admiral, who did not then know that there was any idea of the King coming, explained what the

Belfast

would do on the morning of D-Day. It was clear from what he said that those on board the ship would run considerable risks, and also would see very little of the battle. The Admiral was then asked to withdraw for a few minutes, during which it was decided to ask his opinion on the advisability of His Majesty also going to sea in the

Belfast.

The Admiral immediately made it clear that he was not in favour of this. I then said that I should feel obliged to ask the Cabinet and to disclose the Admiral’s opinion about the risk, and I said I was sure they would not recommend His Majesty to go. Ramsay then departed. The King said that if it was not right for him to go, neither was it right for me. I replied I was going as Minister of Defence in the exercise of my duty. Sir Alan Lascelles, who the King remarked was “wearing a very long face,” said that “His Majesty’s anxieties would be increased if he heard his Prime Minister was at the bottom of the English Channel.” I replied that that was all arranged for, and that moreover I considered the risk negligible. Sir Alan said that he had always understood that no Minister of the Crown could leave the country without the

Sovereign’s permission. I answered that this did not apply, as I should be in one of His Majesty’s ships. Lascelles said the ship would be well outside territorial waters. The King then returned to Buckingham Palace.

* * * * *