Closing the Ring (83 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

Only on three days in each lunar month were all the desired conditions fulfilled. The first three-day period after May 31, General Eisenhower’s target date, was June 5, 6, and 7. Thus was June 5 chosen. If the weather were not propitious on any of those three days, the whole operation would have to be postponed at least a fortnight—indeed, a whole month if we waited for the moon.

* * * * *

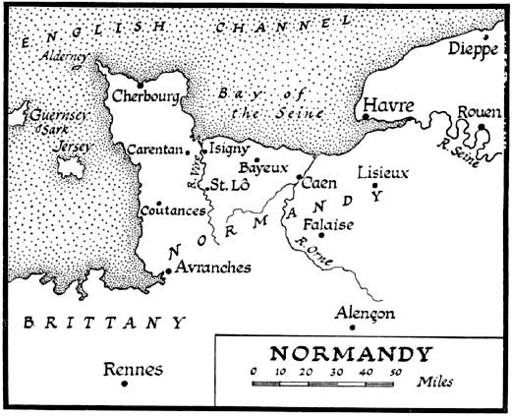

By April our plans were taking final shape. The Second British Army, under General Dempsey, was to land three divisions on beaches north and northwest of Caen. One airborne division was to be dropped, a few hours before, northeast of Caen to capture the bridges over the lower Orne and protect the eastern flank. On the British right, the First United States Army, under General Omar Bradley, was to land one division on the coast east of the Vire estuary and one division north of it. The latter would be aided by a previous drop of two airborne divisions a few miles inland. Each army had one division in ships for immediate reinforcement.

The first objectives of the attack included Caen, Bayeux, Isigny, and Carentan. When these were gained, the Americans

would advance across the Cotentin peninsula, and also drive northward to capture Cherbourg. The British would protect the American flank from counter-attack from the east, gaining ground south and southeast of Caen where we could create airfields and use our armour. It was hoped to reach the line Falaise-Avranches three weeks after the landing, and, with the strong reinforcements by that time ashore, to break out eastward towards Paris, northeastward towards the Seine, and westward to capture the Brittany ports.

These plans depended on our ability to maintain a rapid build-up over the beaches. To co-ordinate all the intricate shipping movements a special organisation was established at the Supreme Commander’s Headquarters at Portsmouth, with subordinate inter-Service bodies at the embarkation ports. This enabled the commanders on the far shore to control the flow of supplies to their beaches. A similar organisation controlled supplies from the air. The nourishing and expanding of the

numerous organisations on the beaches of France was a prime feature. They would soon be as busy as a major port.

The Navy’s task would be to carry the Army safely across the Channel and support the landing with all available means; thereafter to ensure the timely arrival of reinforcements and supplies, despite all the hazards of the sea and the enemy. Admiral Ramsay commanded two Task Forces, one British and the other American. The Eastern Task Force, under Admiral Vian, would control all naval operations in the British sector. Admiral Kirk, U.S.N., operated similarly for the American First Army. These two commands contained five assault forces, each carrying the fighting elements of a division and each having its own specialised craft to give close support to the troops in the landings. Here was the hard core of the attack. Surrounding and protecting the assault forces would be the powerful Allied Navies and Air Forces.

From the embarkation ports, stretching from Felixstowe on the east to the Bristol Channel on the west, shipping would be brought coastwise in convoy to a rendezvous near the Isle of Wight. From here the vast armada would sail to Normandy. Because of the great congestion in our southern ports and to help our deception plans, the heavy naval bombarding forces would assemble in the Clyde and at Belfast.

Mines were the chief danger during the approach, although U-boats and light surface craft would also present a threat, and minesweeping was of vital concern. A mine barrier extended across our line of approach, and we could not tell what more the enemy might do at the last moment in the assault area itself. Ten separate channels through the barrier must be swept for the assault convoys, and thereafter the whole area must be searched. Twenty-nine flotillas of minesweepers were assembled, amounting to about three hundred and fifty craft.

The mighty offensive, assigned to Bomber Command and described in an earlier chapter, had already been in progress for many weeks. The Allied Tactical Air Forces, under Air Chief-Marshal Leigh-Mallory, not only helped the heavy bombers to destroy enemy communications and isolate the battle area, but also had to defeat the enemy’s air force before the battle began on land. German airfields and installations were attacked for three weeks before D-Day in growing weight of bombardment, while fighter sweeps tempted the reluctant enemy to battle. For the assault itself the initial task was to protect our naval forces and convoys from attack by sea or air; then to neutralise the enemy’s radar installations, and, while joining in the joint bombardment plan, additionally to provide fighter cover over the anchorages and beaches. Three airborne divisions were to be delivered safely and in darkness onto their objectives, together with a number of special parties to stir and encourage the seething Resistance Movement.

* * * * *

The bombardment to cover the first landing was a prime factor. Before D-Day preliminary air attacks had been delivered on many coastal batteries, not merely those covering the invasion beaches, but, for the sake of deception, all along the French shore. On the night before D-Day, a great force of British heavy bombers would attack the ten most important batteries that might oppose the landings. At dawn their place was to be taken by medium bombers and ships’ gunfire, directed by spotting aircraft. About half an hour after first light, the full weight of the United States heavy and medium bombers would fall upon the enemy defences. A great variety of guns and rockets mounted in naval assault craft would join in a crescendo of fire.

* * * * *

Of course, we had not only to plan for what we were really going to do. The enemy was bound to know that a great invasion was being prepared; we had to conceal the place and time of attack and make him think we were landing somewhere else and at a different moment. This alone involved an immense amount of thought and action. Coastal areas were banned to visitors; censorship was tightened, letters after a certain date were held back from delivery; foreign embassies were

forbidden to send cipher telegrams and even their diplomatic bags were delayed.

Our major deception was to pretend that we were coming across the Straits of Dover. It would not be proper even now to describe all the methods employed to mislead the enemy, but the obvious ones of simulated concentrations of troops in Kent and Sussex, of fleets of dummy ships collected in the Cinque Ports, of landing exercises on the near-by beaches, of increased wireless activity, were all used. More reconnaissances were made at or over the places we were

not

going to than at the places we were. The final result was admirable. The German High Command firmly believed the evidence we obligingly put at their disposal. Rundstedt, the Commander-in-Chief on the Western Front, was convinced that the Pas de Calais was our objective.

* * * * *

The concentration of the assaulting forces—176,000 men, 20,000 vehicles, and many thousand tons of stores, all to be shipped in the first two days—was in itself an enormous task. It was handled principally by the War Office and the railway authorities, and with great success. From their normal stations all over Britain the troops were brought to the southern counties, into areas stretching from Ipswich round to Cornwall and the Bristol Channel. The three airborne divisions, which were to drop on Normandy before the sea assault, were assembled close to the airfields whence they would set out. From their concentration areas in rear troops were brought forward for embarkation in assigned priority to camps in marshalling areas near the coast. At the marshalling camps they were divided up into detachments corresponding to the ship- or boat-loads in which they would be embarked. Here every man received his orders. Once briefed, none were permitted to leave camp. The camps themselves were situated near to the embarkation points. These were ports or “hards”—i.e., stretches of beach concreted to allow of easy embarkation on smaller craft. Here they were to be met by the naval ships.

It seemed most improbable that all this movement by sea and land would escape the attention of the enemy. There were many tempting targets for their Air, and full precautions were taken. Nearly seven thousand guns and rockets and over a thousand balloons protected the great masses of men and vehicles. But there was no sign of the Luftwaffe. How different things were four years before! The Home Guard, who had so patiently waited for a worth-while job all those years, now found it. Not only were they manning sections of antiaircraft and coast defences, but they also took over many routine and security duties, thus releasing other soldiers for battle.

All Southern England thus became a vast military camp, filled with men trained, instructed, and eager to come to grips with the Germans across the water.

1

Author’s italics.

17

Rome

May 11—June 9

The Regrouping of the Allied Armies___Alexander’s Great Offensive Begins, May

11___

General Juin Takes Ausonia___The Poles Capture the Cassino Monastery___General Advance of the Allies___My Telegram to Alexander of May

17

and His Reply___The Climax Approaches___The Canadian Corps in the Liri Valley___The Anzio Army under General Truscott Advances to the Alban Hills and Valmontone___Stubborn German Resistance___Alexander’s Telegram of May

30

and My Reply___Valmontone Captured by the Americans, June

2___

The War Cabinet Send Congratulations to All___The Allied Entry into Rome, June

5___

My Telegram to Stalin of June

5___

Magnificent Achievements of the Russian Armies___German Retreat Along the Whole Eastern Front___Hitler Faces Impending Doom on Three Fronts.

T

HE REGROUPING OF OUR FORCES

in Italy was undertaken in great secrecy. Everything possible was done to conceal the movements from the enemy and to mislead him. By the time they were completed, General Clark, of the Fifth Army, had over seven divisions, four of them French, on the front from the sea to the river Liri; thence the Eighth Army, now under General Leese, continued the line through Cassino into the mountains with the equivalent of nearly twelve. Six divisions had been packed into the Anzio beachhead ready to sally forth at the best moment; the equivalent of only three remained in the Adriatic sector. In all the Allies mustered over twenty-eight divisions.

Opposed to them were twenty-three German divisions, but

our deception arrangements, which included the threat of a landing at Civitavecchia, the seaport of Rome, had puzzled Kesselring so well that they were widely spread. Between Cassino and the sea, where our main blows were to fall, there were only four divisions, and reserves were scattered and at a distance. Our attack came unexpectedly. The Germans were carrying out reliefs opposite the British front, and one of their Army Commanders had planned to go on leave.

In the morning of May 11, Alexander and I exchanged telegrams.

Prime Minister to General Alexander

11 May 44

All our thoughts and hopes are with you in what I trust and believe will be a decisive battle, fought to a finish, and having for its object the destruction and ruin of the armed force of the enemy south of Rome.

General Alexander to Prime Minister

11 May 44

All our plans and preparations are now complete and everything is ready. We have every hope and every intention of achieving our object, namely, the destruction of the enemy south of Rome. We expect extremely heavy and bitter fighting, and we are ready for it. I shall signal you our private code-word when the attack starts.

The great offensive began at eleven that night, when the artillery of both our armies, two thousand guns, opened a violent fire, reinforced at dawn by the full weight of the Tactical Air Force. North of Cassino, the Polish Corps tried to surround the monastery on the ridges that had been the scene of our previous failures, but they were held and thrown back. The British XIIIth Corps, with the 4th British and 8th Indian Divisions leading, succeeded in forming small bridgeheads over the Rapido River, but had to fight hard to hold them. On the Fifth Army front the French soon advanced to Monte Faito, but on the seaward flank the IId United States Corps ran into stiff opposition and struggled for every yard of ground. After thirty-six hours of heavy fighting, the enemy began to weaken. The French Corps took Monte Majo, and General

Juin pushed his motorised division swiftly up the river Garigliano to capture San Ambrogio and San Apollinare, thus clearing all the west bank of the river. The XIIIth Corps bit more deeply into the strong enemy defences across the Rapido, and on May 14, with the 78th Division coming up to reinforce, began to make good progress. The French thrust forward again up the Ausente Valley and took Ausonia, and General Juin launched his Goums

1

across the trackless mountains westward from Ausonia. The American Corps succeeded in capturing Santa Maria Infante, for which they had been fighting for so long. The two German divisions, which on this flank had had to support the attack of six divisions of the Fifth Army, had suffered crippling losses, and all the German right flank south of the Liri was breaking.