Closing the Ring (78 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

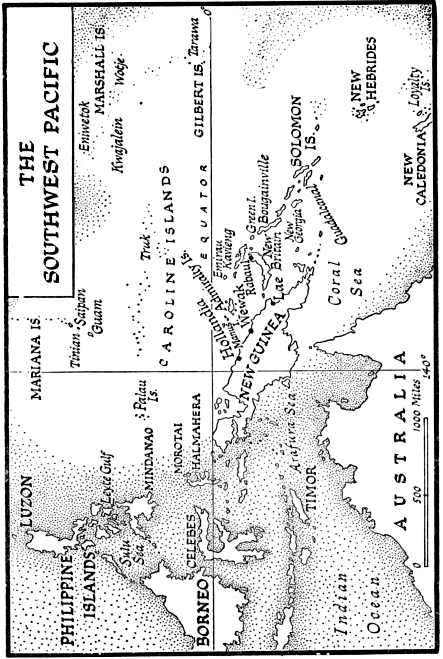

In April, General MacArthur made an amphibious leap of four hundred miles. He by-passed fifty thousand Japanese around Wewak, and landed an American division at Aitape and two more near Hollandia. The Japanese air force had been thoroughly pounded, and three hundred and eighty machines were found destroyed. Allied superiority by sea and air was henceforward so decisive that MacArthur could select whatever objectives suited him best, and leave behind him large pockets of Japanese to be dealt with later. His final bound was to Biak Island, where the 41st United States Division had a fierce struggle against an enemy garrison nearly ten thousand strong. A convoy of a dozen Japanese warships was destroyed or crippled by air attack as they tried to bring reinforcements, and the island was effectively in American possession before the end of June 1944. This marked the end of the two-year struggle in New Guinea, where the stubborn resistance of the enemy, the physical difficulties of the country, the ravages of disease, and the absence of communications made the campaign as arduous as any in history.

* * * * *

Farther east, at the beginning of July 1943, and simultaneously with General MacArthur’s attack on Salamaua, Admiral Halsey had struck in New Georgia. After several weeks of severe fighting both this and the adjacent islands were won. Air fighting again dominated the scene, and the ascendancy of the American airmen soon proved decisive. Japanese losses in the air now exceeded those of the Americans by four or five to one.

In July and August, a series of naval actions gave the Americans command of the sea. By September, the backbone of Japanese resistance had been broken, and although severe fighting continued at Bougainville and other islands, the campaign in the Solomons was ended by December 1943. Such positions as remained in enemy hands had been neutralised and could now be safely by-passed and left to wilt.

Rabaul itself, in New Britain, became the next centre of attack. During November and December, it was heavily and repeatedly struck by Allied air forces, and in the last days of 1943, General MacArthur’s amphibious forces landed on the western extremity of New Britain at Cape Gloucester. It was now decided to by-pass Rabaul. An alternative base was therefore needed to sustain the advance to the Philippines, and this was within MacArthur’s grasp at Manus Island, in the Admiralty Group. In February 1944, the first stage of this envelopment was accomplished by the seizure of Green Island, one hundred and twenty miles east of Rabaul. This was followed by the brilliant capture of the whole Admiralty Group, to the westward. In March, Emirau Island, immediately to the north, was taken by Admiral Halsey, and the isolation of Rabaul was complete. The air and sea surrounding these islands thus passed entirely under American control.

* * * * *

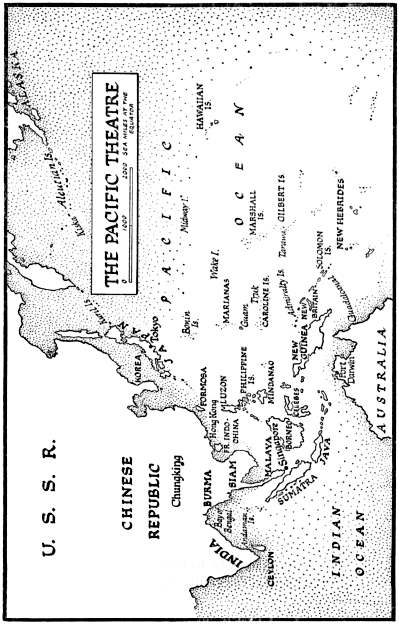

Meanwhile, the main American maritime forces, under Admiral Nimitz, began to concentrate for his drive through the island groups near the equator, which were the outposts defending the Japanese fleet base at Truk, in the Carolines. The most easterly of these groups, the Gilberts, seized from the British in 1941, was chosen for the first attack. In October 1943, Admiral Spruance, who had gained fame at Midway, was appointed to command the Central Pacific force. In November, while Halsey was attacking Bougainville, Spruance struck at Tarawa, in the Gilberts. The island was strongly fortified, and was held by about thirty-five hundred Japanese troops. The

landing by the 2d Marine Division was bitterly contested, in spite of heavy preliminary air attacks. After four fierce days, in which casualties were heavy, the island was captured.

With Tarawa eliminated, the way was clear for attack on the Marshall Group, to the north and west of the Gilberts. In February 1944, they were the object of amphibious operations on the greatest scale yet attempted in the Pacific, and by the end of the month the Americans were victorious. Without pause, Spruance began the next phase of his advance, the softening by air attack of Japanese defences in the Carolines and Marianas. The flexibility of seaborne attack in an ocean area is the most remarkable feature of these operations. While we in Europe were making our final preparations for “Overlord” with immense concentration of force in the narrow waters of the Channel, Spruance’s carriers were ranging over huge areas, striking at islands in the Marianas, Palau, and Carolines, deep within the Japanese defensive perimeter, and at the same time helping MacArthur in his attack on Hollandia. On the eve of “Overlord,” Japan’s strength was everywhere on the wane; her defence system in the Central Pacific had been breached at many points and was ripe for disruption.

Summing up these operations in the Southwest Pacific, General Marshall could report that in a little over twelve months the Allies had “pushed 1300 miles closer to the heart of the Japanese Empire, cutting off more than 135,000 enemy troops beyond hope of rescue.”

* * * * *

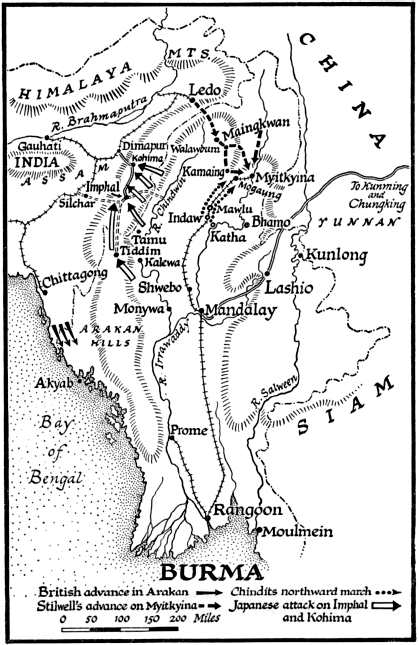

The curtain must now rise on a widely different scene in Southeast Asia. For more than eighteen months the Japanese had been masters of a vast defensive arc covering their early conquests. This stretched from the jungle-covered mountains of Northern and Western Burma, where our British and Indian troops were at close grips with them, across the sea to the Andamans and the great Dutch dependencies of Sumatra and Java, and thence in an easterly bend along the string of lesser islands to New Guinea.

The Americans had established a bomber force in China

which was doing good work against the enemy’s sea communications between the mainland and the Philippines. They wanted to extend this effort by basing long-range aircraft in China to attack Japan itself. The Burma Road was cut, and they were carrying all supplies for them and the Chinese armies by air over the southern spurs of the Himalayas, which they called “the Hump.”

This was a stupendous task. I had always advocated air aid to China and the improvement of the air route and protection of the airfields, but I hoped this might be done by forces essentially airborne and air-sustained on the Wingate model, but on a larger scale. The wish of the Americans to succour China, not only by an ever-increasing air-lift, but also by land, led to heavy demands upon Britain and the Indian Empire. They pressed as a matter of the highest urgency and importance the making of a motor road from their great air starting-point at Ledo through five hundred miles of jungles and mountains into Chinese territory. Only one narrow-gauge, single-line railway ran through Assam to Ledo. It was already in constant use for many other needs, including the supply of the troops who held the frontier positions; but in order to build the road to China, the Americans wanted us to reconquer Northern Burma first and quickly.

* * * * *

Certainly we favoured keeping China in the war and operating air forces from her territory, but a sense of proportion and the study of alternatives were needed. I disliked intensely the prospect of a large-scale campaign in Northern Burma. One could not choose a worse place for fighting the Japanese. Making a road from Ledo to China was also an immense, laborious task, unlikely to be finished until the need for it had passed. Even if it were done in time to replenish the Chinese armies while they were still engaged, it would make little difference to their fighting capacity. The need to strengthen the American air bases in China would also, in our view, diminish as Allied advances in the Pacific and from Australia gained us

airfields closer to Japan. On both counts therefore we argued that the enormous expenditure of man-power and material would not be worth while. But we never succeeded in deflecting the Americans from their purpose. Their national psychology is such that the bigger the Idea, the more wholeheartedly and obstinately do they throw themselves into making it a success. It is an admirable characteristic, provided the Idea is good.

We of course wanted to recapture Burma, but we did not want to have to do it by land advances from slender communications and across the most forbidding fighting country imaginable. The south of Burma, with its port of Rangoon, was far more valuable than the north. But all of it was remote from Japan, and for our forces to become side-tracked and entangled there would deny us our rightful share in a Far Eastern victory. I wished, on the contrary, to contain the Japanese in Burma, and break into or through the great arc of islands forming the outer fringe of the Dutch East Indies. Our whole British-Indian Imperial Front would thus advance across the Bay of Bengal into close contact with the enemy, by using amphibious power at every stage. This divergence of opinions, albeit honestly held and frankly discussed, and with decisions loyally executed, continued. It is against this permanent background of geography, limited resources, and clash of policies that the story of the campaign should be read.

* * * * *

The Washington standpoint was clearly set forth to me by the President.

President Roosevelt to Prime Minister

25 Feb. 44

My Chiefs of Staff are agreed that the primary intermediate objective of our advance across the Pacific lies in the Formosa-China coast-Luzon area. The success of recent operations in the Gilberts and Marshalls indicates that we can accelerate our movements westward. There appears to be a possibility that we can reach the Formosa-China-Luzon area before the summer of 1945. From the time we enter this vital zone until we gain a firm lodgment in this

area, it is essential that our operations be supported by the maximum air power that can be brought to bear. This necessitates the greatest expansion possible of the air strength based on China.

I have always advocated the development of China as a base for the support of our Pacific advances, and now that the war has taken a greater turn in our favour, time is all too short to provide the support we should have from that direction.

It is mandatory therefore that we make every effort to increase the flow of supplies into China. This can only be done by increasing the air tonnage or by opening a road through Burma.

Our occupation of Myitkyina will enable us immediately to increase the air-lift to China by providing an intermediate air-transport base as well as by increasing the protection of the air route.

General Stilwell is confident that his Chinese-American Force can seize Myitkyina by the end of this dry season, and once there, can hold it, provided Mountbatten’s 4th Corps from Imphal secure the Shwebo Monywa area. I realise this imposes a most difficult task, but I feel that with your energetic encouragement Mountbatten’s commanders are capable of overcoming the many difficulties involved.

The continued build-up of Japanese strength in Burma requires us to undertake the most aggressive action within our power to retain the initiative and prevent them from launching an offensive that may carry them over the borders into India. … I most urgently hope therefore that you back to the maximum a vigorous and immediate campaign in Upper Burma.

* * * * *

The campaign had been opened in December, when General Stilwell, with two Chinese divisions, organised and trained by himself in India, crossed the watershed from Ledo into the jungles below the main mountain ranges.

1

He was opposed by the renowned Japanese 18th Division, but forged ahead steadily, and by early January had penetrated forty miles, while the road-makers toiled behind him. In the south, the British XVth Corps, under General Christison, began their advance down the Arakan coast on January 19. At the same time the Allied air forces redoubled their efforts, and, with the aid of

newly arrived Spitfires, gained a degree of air superiority which was shortly to prove invaluable.