Closing the Ring (81 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

3. Accordingly, I should be very grateful if you could let me know whether there is any specific American operation in the Pacific, (

a

) before the end of 1944 or (

b

) before the summer of 1945, which would be hindered or prevented by the absence of a British Fleet detachment.

4. On the other hand, the movement of the Japanese Fleet to Singapore, which coincided

inter alia

with their knowledge of the movement of our battleship squadron into the Indian Ocean, seems to show their sensitiveness about the Andamans, Nicobars, and Sumatra. It would surely be an advantage to you if, by keeping up the threat in the Bay of Bengal, we could detain the Japanese Fleet or a large portion of it at Singapore, and thus secure you a clear field in the Pacific to enable your by-passing process and advance to develop at full speed.

5. General Wedemeyer is able to unfold all Mountbatten’s plans

in the Indian theatre and the Bay of Bengal. They certainly seem to fit in with the kind of requests which Chiang Kai-shek was making, which you favoured but which we were unable to make good before the monsoon on account of the Mediterranean and “Overlord” operations. I am personally still of opinion that amphibious action across the Bay of Bengal will enable all our forces and establishments in India to play their highest part in the next eighteen months in the war against Japan. We are examining now the logistics in detail and,

prima facie

, it seems that we could attack with two or three times the strength the islands across the Bay of Bengal and thereafter the Malay peninsula than we could by prolonging our communications about nine thousand miles round the south of Australia and operating from the Pacific side and on your southern flank. There is also the objection of dividing our Fleet and our effort between the Pacific and Indian Oceans and throwing out of gear so many of our existing establishments from Calcutta to Ceylon and way back in the Suez Canal zone.

6. Before however reaching any final conclusions in my mind about this matter, I should like to know what answer you would give to the question I posed in paragraph 3, namely, would your Pacific operations be hindered if, for the present at any rate and while the Japanese Fleet is at Singapore, we kept our centre of gravity in the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal and planned amphibious operations there as resources come to hand.

The President’s reply to my direct question was conclusive.

President Roosevelt to Prime Minister

13 Mar. 44

(

a

) There will be no specific operation in the Pacific during 1944 that would be adversely affected by the absence of a British Fleet detachment. (

b

) It is not at the present time possible to anticipate with sufficient accuracy future developments in the Pacific to be certain that a British Fleet detachment will not be needed there during the year of 1945, but it does not now appear that such a reinforcement will be needed before the summer of 1945.

In consideration of recent enemy dispositions, it is my personal opinion that unless we have unexpected bad luck in the Pacific your naval force will be of more value to our common effort by remaining in the Indian Ocean.

All of the above estimates are of course based on current conditions and are therefore subject to change if the circumstances change.

* * * * *

Thus fortified upon the distressing controversy in which I and my Cabinet colleagues were engaged with the Chiefs of Staff, I felt it my duty to give a ruling. In this case I addressed myself to each of the Chiefs of Staff personally and not collectively to them as a Committee.

Prime Minister to First Sea Lord, C.I.G.S. and C.A.S.

20 Mar. 44

I have addressed the attached minute to each of the Chiefs of Staff personally.

My question and the President’s reply are directed … solely to the point as to whether there is any obligation to the American authorities that we send a detachment of the British Fleet to the Pacific before the summer of 1945, and whether their operations would be hampered if we stood out. We now know that there is no obligation and that their operations will not be hampered, also that they will not in any case require our assistance (barring some catastrophe) before the summer of 1945. We are therefore free to consider the matter among ourselves and from the point of view of British interests only.

. …. …. …

3. The serious nature of the present position has been brought home to me by the reluctance of the Chiefs of Staff to meet with their American counterparts for fear of revealing to the United States their differences from me and my Cabinet colleagues. The Ministers on the Defence Committee are convinced, and I am sure that the War Cabinet would agree if the matter were brought before them, that it is in the interest of Britain to pursue what may be termed the “Bay of Bengal Strategy,” at any rate for the next twelve months. I therefore feel it my duty, as Prime Minister and Minister of Defence, to give the following rulings:

(

a

) Unless unforeseen events occur, the Indian theatre and the Bay of Bengal will remain, until the summer of 1945, the centre of gravity for the British and Imperial war effort against Japan.

(

b

) All preparations will be made for amphibious action across the Bay of Bengal against the Malay peninsula and the various island outposts by which it is defended, the ultimate objective being the reconquest of Singapore.

(

c

) A powerful British Fleet will be built up based on Ceylon, Adu Atoll, and East Indian ports, under the shield of our strong shore-based aircraft. The fleet train for this Eastern Fleet must be developed as fast as possible, subject to the priority needs of “Overlord” and the Mediterranean, and the necessary feeding of this country on its present rations.

(

d

) The plans of Southeast Asia Command for amphibious action across the Bay of Bengal should be examined, corrected, and improved with the desire of engaging the enemy as closely and as soon as possible.

(

e

) The Reconnaissance Mission to Australia should be sent as soon as I have approved the personnel. They should report promptly upon the existing facilities in Australia and on the recaptured islands to the north of it, and propose measures for carrying the Eastern Fleet and its fleet train, with any additions that may be required, into the Southwest Pacific and basing it on Australian ports should we at any time wish to adopt that policy.

4. I should be very ready to discuss the above rulings with the Chiefs of Staff in order that we may be clear in our minds as to the line we are going to take in discussions with our American friends. Meanwhile, with this difference on long-term plans settled, we may bend ourselves to the tremendous and urgent tasks which are now so near and in which we shall have need of all our comradeship and mutual confidence.

These rulings were accepted. Nevertheless, in a scene melting and reshaping so rapidly, I preferred to keep the options open. If the Bay of Bengal were excluded by the pressure of the main Japanese Fleet, means might be found to support General MacArthur’s advance by operations on his flank. This plan became known in our circle as the “middle strategy.” It aimed at forming a British and Australian task force of all arms under the over-all control of General MacArthur, to assist in the liberation of the East Indies, and at the same time to outflank Singapore from the south. This did not mature. Happily, the course of events soon changed fundamentally the conditions which prevailed or could be foreshadowed at the Cairo Conference or in the months which followed, and anyhow the war with Japan ended in a manner and at a date which no one dreamed of at the time of the discussions I have described.

16

Preparations for “Overlord”

Hard Memories___The Cross-Channel Plan___The Commanders___The Increased Weight of the Assault___The Mulberry Harbours___Plan for Airborne Attack___Waterproofing of Vehicles___Fire Plans of the Naval Bombardment___My Telegram to General Marshall, March

11___

Training the Troops in Amphibious Operations___D-Day and H-Hour___Final Dispositions and First Objectives___The Navy’s Task___The Air Offensive___Deception Devices___The Germans Misled___All Southern England One Vast Camp.

T

HOUGHT

ARISING

FROM

FACTUAL

EXPERIENCE

may be a bridle or a spur. The reader of these volumes will be aware that, while I was always willing to join with the United States in a direct assault across the Channel on the German sea-front in France, I was not convinced that this was the only way of winning the war, and I knew that it would be a very heavy and hazardous adventure. The fearful price we had had to pay in human life and blood for the great offensives of the First World War was graven in my mind. Memories of the Somme and Passchendaele and many lesser frontal attacks upon the Germans were not to be blotted out by time or reflection. It still seemed to me, after a quarter of a century, that fortifications of concrete and steel armed with modern fire-power, and fully manned by trained, resolute men, could only be overcome by surprise in time or place by turning their flanks, or by some new and mechanical device like the tank. Superiority of bombardment, terrific as it may be, was no final answer. The defenders could easily have ready other lines behind their first,

and the intervening ground which the artillery could conquer would become impassable crater-fields. These were the fruits of knowledge which the French and British had bought so dearly from 1915 to 1917.

Since then new factors had appeared, but they did not all tell the same way. The fire-power of the defence had vastly increased. The development of minefields both on land and in the sea was enormous. On the other hand, we, the attackers, held air supremacy, and could land large numbers of paratroops behind the enemy’s front, and above all block and paralyse the communications by which he could bring reinforcements for a counter-attack.

Throughout the summer months of 1943, General Morgan and his Allied inter-Service Staff had laboured at the plan. In a

previous chapter

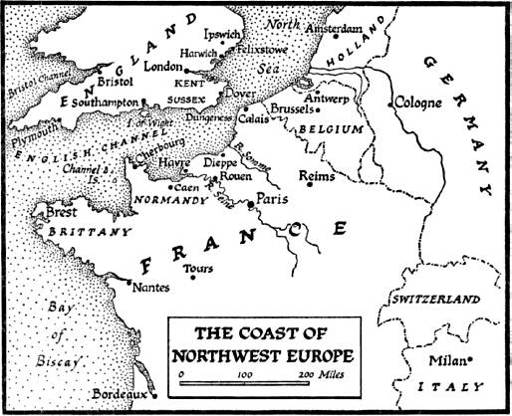

I have described how it was presented to me during my voyage to Quebec for the “Quadrant” Conference. There the scheme was generally approved, but there was one feature of it which requires comment. The size and scope of the first assault on the Normandy beaches was necessarily limited by the numbers of landing-craft available. General Morgan’s instructions were to plan an assault by three divisions, with two divisions as an immediate follow-up. He accordingly proposed to land the three divisions on the coast between Caen and Carentan. He would have liked to land part of the force north of Carentan, nearer to Cherbourg, but he thought it unwise to divide so small a force. The estuary of the river Vire at Carentan was marshy and it would have been difficult for the two wings of the attack to keep in touch. No doubt he was right. I would certainly have preferred a stronger attack on a broader front, but at that time, ten months before the event, we could not be sure of having enough landing-craft.

It was the absence of important harbours in all this stretch of coast which had impelled Mountbatten’s Staff to propose the synthetic harbours. The decisions at Quebec confirmed the need and clarified the issues. I kept in touch with the development of this project, which was pressed forward by a committee of experts and Service representatives, summoned

by Brigadier Bruce White of the War Office, himself an eminent civil engineer. It was a tremendous undertaking, and high credit is due to many, not least to Major-General Sir Harold Wernher, whose task it was to co-ordinate the many interests concerned.

Here too should be mentioned “Pluto,” the submarine pipelines which carried petrol from the Isle of Wight to Normandy and later from Dungeness to Calais. This idea and many others owed much to Mountbatten’s Staff. Space forbids description of the many contrivances devised to overcome the formidable obstacles and minefields guarding the beaches. Some were fitted to our tanks to protect their crews; others served the landing-craft. All these matters aroused my personal interest, and, when it seemed necessary, my intervention.

* * * * *

General Morgan and his Staff were well content with the approval given at Quebec to their proposals. The troops could now begin their training and their special equipment could be made. For this Morgan had been given powers greater than a Staff officer usually wields.

The discussions which led to the appointment of General Eisenhower to the Supreme Command and of General Montgomery to command the expeditionary army have already been related. Eisenhower’s Deputy was Air Chief Marshal Tedder. Air-Marshal Leigh-Mallory was appointed to the Air and Admiral Ramsay to the Naval Command. General Eisenhower brought with him General Bedell Smith as his Chief of Staff, to whom General Morgan was appointed Deputy.