Chatham Dockyard (6 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

… there was in one place a sort of arches like a bridge of brick-work, they told me the use of it was to let in the water there and so they put the masts into season.

14

Ollivier himself says nothing of the use of the mast pond but does refer to the mast houses, of which there were twelve at this time, explaining that this was where the mast makers ‘work their masts’.

15

During his spying mission on the yard, Ollivier observed the

making of the main mast for

Royal Sovereign

, a 100-gun first rate that was undergoing repairs in one of the larger dry docks. This was a major undertaking as the mast, comprising lower, top and topgallant sections, had a total height of 114ft (34.7m). In all, twenty fir sticks would be required, with the lower mast section being ‘made up of two trees joined by a scarph [join] 32ft [9.75m] long’ and joined with ‘plain coaks’ or tenon joints. On the outside, the two mast sticks upon being joined together were shaped into the form of an octagon and to ‘each of these eight faces a side tree [was] fayed’ and fastened with ‘nail and iron bolts, which pass right through the mast, and which are clenched over roves’.

16

Immediately to the east of the docks and slips, and occupying much of the central part of the yard, was a vast area set aside for the storage of timber. According to Ollivier, most of this was ‘East country plank, or from New England’. He also noted that timbers were often marked, this demonstrating their country of origin. Whilst Ollivier may have been correct with regard to his observation as to the origin of the timbers he was looking at, he made nothing of the importance of oak grown in the two counties of Kent and Sussex. Generally, this was considered by the Navy Board to be without rival and was specifically reserved for the frames that formed the hull of any large and important warship. The reference to the timber being marked is worth exploring a little further as this was a device to more effectively manage and account for all timbers in the yard. It is unlikely, despite Ollivier’s claim, that the markings indicated a country of origin. A series of old ship timbers that were used in the construction of the wheelwright’s shop, a structure added to the dockyard in 1790, had markings that seem to indicate only the dockyard that first received the timber together with the year and a reference number. In later years, these markings were to carry even more information but never, so it would seem, its originating country.

In giving his attention to this area of timber storage, Ollivier must have been surprised by the methods used to store this huge shipbuilding resource: it simply being ‘piled one timber on another’. Quite simply, with the cut marks difficult to see amidst those disorganised piles, there was no way of easily extracting a particular timber, identifying its age or determining whether it had been adequately seasoned. Furthermore, through lack of adequate ventilation, timbers would often begin to rot while in storage and then be introduced into ships under construction or repair. Possibly this helps explain why ships constructed during the eighteenth century had such a short service life, with Clive Wilkinson, in a recent study, indicating that ships of the line would only see twelve to sixteen years of service. Furthermore, Wilkinson suggests that the problem peaked during the 1730s, coinciding with Ollivier’s spying mission, and was due to an added environmental factor, with strong westerly airflows creating a long series of mild winters. Consequently, timber cut during these years contained greater levels of sap and required even longer periods of seasoning. Given, as demonstrated, that no extended and effective period of seasoning was allowed, Wilkinson notes that ships-of-the-line built during this period had an even shorter period of longevity, estimated as less than nine years on average.

17

One experiment undertaken at Chatham was that of immersing in salt water certain of the shipbuilding timbers. Ollivier indicates that this was being undertaken in a large pond 320ft (97.5m) square. Only one feature of the yard fits this description, that of a

second mast pond that had been added to the yard in 1702 and which stood at the far north of the yard.

18

Into this, Ollivier adds, various timbers, mostly those destined to form the frames of a vessel under construction, were totally submerged for about six months. The effect was to help wash out some of the remaining sap, so making the wood harder and more durable. In turn, timber treated in this fashion also had a tendency to attract moisture and would, therefore be more prone to wet rot. At Chatham, it was not an experiment deemed to have been successful, with Ollivier noting that from the original six months, the length of time for immersion had eventually been reduced to three months and, at the time of his visit to Chatham, it was no more than ‘one or two weeks’ with many frame timbers no longer immersed in this way. However, the scheme was not totally abandoned. While the timber pond was converted back to use as a mast pond shortly after Ollivier’s visit to Chatham, a further and much smaller pond, known as the pickling pond, was created for the immersion of oak timbers. Situated at the centre of the yard, amidst the area set aside for the storage of timber, it measured 210ft (64m) by 90ft (27.4m) and was fitted with a ramp that enabled these heavy timbers to be more easily hauled out when their period in soak had been completed.

19

A common feature of many of the earlier buildings in the dockyard at Chatham is the introduction of reused ships’ timber, such as seen here in the mast house at Chatham that dates to the mid-eighteenth century.

While in the timber storage area, Ollivier’s attention was drawn to a steam kiln that was used for the curving of planks that were to be fitted to both the bow of a ship and the rounded areas toward the stern. In these areas, straight timbers would be inappropriate. As far as the French yards were concerned, timbers were cut to shape using templates. However, this was both time-consuming and costly in the amount of timber used, making Ollivier determined to encourage the introduction of kilns into the French yards. As used at Chatham, seasoned planks were first soaked in fresh water and then placed inside a box that was heated from a coal-fired boiler. Each plank remained in the kiln ‘for about an hour and a quarter for every inch of thickness’. Once removed, the plank was

easily curved to the correct shape and then held in position by a series of stakes. Once cooled, the planks were then taken to the ship under construction for fitting. At that time Chatham had but one steam kiln, this sited just to the north of the two new docks.

A sail loft, a brick building constructed in 1723 which had replaced an earlier building on the same site, stood adjacent to the east wall of the yard, about 370ft (112.8m) forward of the gate. As with a number of buildings and structures that Ollivier would have seen, the sail loft still exists. The sewing and cutting of new sails would have been undertaken on the upper floor, an area completely unencumbered by structural supports. On the lower floor, sails were stored:

… in such a manner that they leave a space [of just over] three feet wide all round the walls of the loft’ while ‘between the walls and sails [was] a curtain, to which [were] made fast a series of brails which [allowed] it to be raised when they wish to air the loft’.

20

Something that Ollivier does not mention, but is an interesting feature of the sail loft, is that some of the ground-floor pillars had been formed out of the ribs of old warships. This was a common practice in the dockyards, with every effort made to reuse timbers from ships that were no longer sea-going and had been brought into dry dock for dismantling. Any reusable timbers might either be used on another ship under construction or, if not up to this standard, used elsewhere in the dockyard. The name and date of the ship from which the timbers were taken is unknown, but would certainly have been one that had originally been built during the previous century. Immediately between the sail loft and the east wall was the sail field used to dry sails taken off vessels when they were brought into dry dock for repair. Of this area, Ollivier noted:

Next to the sail loft is a very great courtyard in which several sheers are set into the earth, 52ft to 62ft [16–19m] high, each braced by four shores, and at the head of these sheers are set up tackles with which the sails can be hoisted up when it is desired to dry them.

21

A further building involved in manufacturing important items of shipboard equipment was the smith’s shop, eventually to be known in the royal dockyards as a smithery. Sited close to the First New Dock it was a substantial, well-ventilated brick building of 130ft (39.6m) in length and 60ft (18.3m) wide. Immediately adjoining was a coal yard and an iron house, the latter being where the uncorked wrought iron was stored. Within the smithery were approximately twenty fires that were most commonly used in the manufacture of anchors, although other items were also produced in the smithery. Ollivier, for instance, when he entered the Chatham smiths’ shop, noted that among work being undertaken was the ‘forging of the mooring chains’ that he indicated were used ‘for securing the cables of ships’ moored in the Medway. Providing further information, he went on to say:

The links of these chains are twice as long as those that we [in France] employ, and are made of iron bar, which is about 0.2in [4.5mm] thicker. I was told they used to make them taller and less fat, and they showed me some that were proportioned like the links of our chains, but they have changed this usage, since the links being fatter are also stronger and are slower to be consumed by rust.

22

Dominating the north end of the yard and adjacent to the Anchor Wharf was the ropery. It was very different to the present-day ropery as overseen by the Chatham Dockyard Historic Trust, as the one seen by Ollivier consisted of timber buildings mostly constructed during the previous century. While the French spy says little about the design of these buildings, he does make the point that ‘there were two roperies’. What he means by this is that there were two adjacent buildings engaged in the process of rope manufacture, one more correctly referred to as the spinning house and the other the ropewalk. In addition, and unmentioned by Ollivier, were the hemp and tarring houses together with several specialised storehouses. Clearly, this was not an area in which Ollivier had a great deal of knowledge, as otherwise he would have dwelt considerably upon the mode of production and how it differed from the manufacture of rope for French warships. As for the use of these various buildings, bales of raw hemp, the basic material required for the manufacture of rope, was stored in the hemp house and removed when required. Initially, the hemp had to be combed, or unknotted, with this undertaken in the hatchelling house, the tangled hemp pulled across a board that was set with sharp pointed iron nails and known as a hatchel. The next stage was to transfer the combed hemp to the spinning house where spinners would twist portions of the hemp fibre over a hook on a manually turned spinning

frame. As the frame turned, the spinner would slowly walk backwards, allowing yarn to be formed under the guidance of his left hand. At the same time, from a bundle of hemp thrown over his shoulder, and using his right hand, further hemp would be added to allow the yarn to lengthen out. The next stage was that of tarring the yarn, carried out in the tarring house, with the yarn pulled through a large kettle containing heated tar.

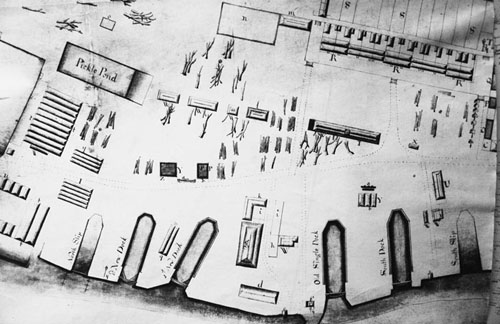

Ollivier was particularly interested in the mid-section of the dockyard where the various docks and slips were located. In this plan of 1746, drawn just nine years after his visit to Chatham, a clear impression emerges of the yard at that time, with measurements taken from this plan agreeing with those recorded by Ollivier at the time of his visit.