Chatham Dockyard (3 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

The Navy Royal, which before the Queen’s time [Elizabeth I] consisted of only small ships, could not in former time come up above Gillingham, three pulls below Chatham. But being in her reign doubled in number and greater ships they ride now between Upnor and Rochester Bridge.

20

As to why this should be, the reasons, so it was suggested, were twofold:

1. The inning of the Marshes above the Bridge has strengthened the Channel and so forced the tide to go quicker [and] ground the River deeper … and this appears in trial betwixt Chatham and the opposite north shore [where] none might in memory have gone a foot over at a low water tide, whereas now [it is] twelve foot at the north shore.

2. By continual riding of the [naval war] ships the cables do continually move up and down and by so beating the ground loosen the silt and wear the Channel deeper.

21

However, the two factors that won the argument and ultimately brought the new facility to Chatham were those of economy and the ease with which ships could be brought to Chatham when compared with Deptford. On the latter point, it was estimated that in the additional time it took for a ship to be transported to Deptford and back ‘a ship with small defects may be repaired’ and to be returned to sea, if sent to Chatham.

22

As for the financial savings, it was considered these could be brought about in two ways. First, it was estimated by making greater use of Chatham, a large number of artisans could be permanently housed there, rather than being sent on a temporary basis and having to be given the inducement of a lodging allowance on top of the normal wage. Inevitably, this made Chatham a popular place to work, since those employed here were considerably more affluent than those employed at Deptford where no such allowances were paid. In 1611, for instance, the Christmas quarter witnessed a total of 259 shipwrights, caulkers and other artisans employed at Chatham and receiving lodging allowance.

23

The second financial economy was that Chatham, due to the availability of nearby land, was unrestricted in the extent to which it could be enlarged, and might completely replace the yard at Deptford. This was certainly a possibility that was seriously canvassed, it being suggested that the facilities at Deptford might, at an estimated sum of £5,000, be sold ‘to Merchants for a Dock Site’.

24

Ultimately, however, Deptford was retained, but it is clear that Chatham was seen as a potential replacement yard, the facilities it eventually gained being considerably beyond those of the initial plan that had not gone much beyond the building of a single dry dock, unloading wharf with additional storehouses and workshops.

With the decision taken to build the new facility at Chatham, careful thought had to be given as to where exactly it should be located. As it stood, the existing yard was too constrained, having insufficient space for the new dry dock and wharf. To overcome this problem, it was decided that considerable additional land would need to be taken in, with 71 acres acquired from three separate landowners: Robert Jackson, the Dean and Chapter of Rochester and the Manor of West Court. Conveniently situated immediately to the north of the original Tudor yard, it forms the bulk of the land that is held by the present-day Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust, while the original area of the yard was to be eventually transferred to the Ordnance Board and converted into a gun wharf.

On the newly acquired site, construction work appears to have begun sometime around 1616, with initial building efforts directed to the new dry dock, wharf and the planned storehouses, together with a brick wall to secure the site. All were to be completed in 1619,

the original combined estimate for construction standing at £4,000. However, the project was to see at least a doubling in cost, it having been decided that if Deptford dockyard was to be replaced, the yard at Chatham should be given an even greater range of facilities. Ultimately, these were to include a new mast pond, sail loft, ropery, residences for officers and a double dock, all of which was completed by 1624. Each of these, in its own right, was a massive undertaking; the ropery, for example, was eventually responsible for the manufacture of most of the rope and cable required by the ships of the Royal Navy. However, the decision to close Deptford was at that time deferred, it being felt that the facilities there were still of value. Perhaps, indeed, this explains the sudden curtailment placed upon the expansion of Chatham, with the decision to build an expensive wet dock or basin (to replace the already existing one at Deptford) being cancelled. As a result, Deptford was to remain, for a great many years, the only royal dockyard with such a facility.

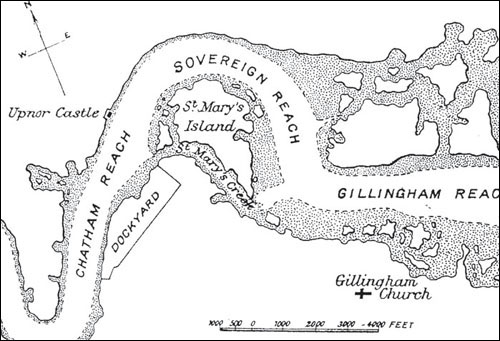

During the early seventeenth century, a completely new yard was established at Chatham, this located to the north of the original yard and closer to Upnor Castle. As this map shows, it lay alongside Chatham Reach and well inside the parish of Chatham.

The expansion of Chatham necessitated a considerable increase in the numbers employed at the yard, with the combined force of artisans and labourers reaching some 800 by about 1660. Within the nearby village of Chatham, which by now should more correctly be referred to as a town, considerable pressure was placed on existing accommodation and bringing about a considerable demand for new housing. From having once been a typical farming village, Chatham was rapidly becoming a crowded, unhealthy metropolis that had little in the way of carefully planned or delicately beautiful buildings. Instead, it was the recipient of hastily built and densely packed houses for the working classes, with the more affluent choosing to live beyond the perimeters of this newly developing township.

Among those who aided the construction of housing suitable for the artisans of the yard was Phineas Pett, a senior officer of the yard, and one of the leading shipbuilders of the day. He was also someone who never missed a trick when it came to the accumulation of money. Within the dockyard itself, and while serving as Master Shipwright, he found himself charged, on two occasions, with major scams that involved the misuse and sale of considerable amounts of government property.

25

As for his involvement in the housing scheme, Pett, in a classic case of insider dealing, made his first land purchase in 1616, aware that the government was about to push forward on its scheme to expand the dockyard and so increase the numbers employed there. In his autobiography he noted, ‘The 8th day of April [1616] I bought a piece of ground of Christopher Collier, lying in a placed called the Brook in Chatham, for which I paid him £35 ready moneys’.

26

Just four weeks later he made a further acquisition, ‘The 13th day of May, I bought the rest of the land at the Brook, of John Griffin and Robert Griffin, brothers, and a lease of their sister, belonging to the College of Rochester’.

27

Before many months had passed, and like a highly skilled player of the board game Monopoly, he soon ensured that these once-vacant sites were now packed with tiny houses that were designed to inflate his own personal income.

Phineas Pett, a slippery character with a super-charged ability to avoid recrimination and punishment, was appointed to the post of resident Commissioner at Chatham in 1630. Indeed, he was the very first to hold such office, it being a newly created post that had not yet been adopted in any other yard. This now made Pett entirely responsible for coordinating the general workings of the yard as well as providing him with a position on the Navy Board, the body in London that was charged with administering all matters connected with the civilian side of the Navy. Given his propensity for lining his own pocket, Pett was now in a unique position. In striding around the yard, he would identify various items of naval property and condemn portions of it as ‘decayed property’. In the resulting sale, for the dockyard regularly disposed of such materials in this way, Pett appears to have retained some of the sale money for himself. Eventually this did come to the attention of other officers on the Navy Board, resulting in his temporary removal from office in February 1634. But Pett had influential friends, not least of which was the reigning monarch, Charles I (on the throne 1625–49). Only a week later, having been informed of the situation, he had Pett quickly reinstated with a full pardon. Pett, unharmed by such charges, remained resident Commissioner until 1647 when he happily handed the office, together with his position on the Navy Board, over to his son Peter, an equally skilled shipbuilder and embezzler of government money.

Another name to conjure with is that of Samuel Pepys who, during the mid-seventeenth century, became a frequent visitor to Chatham dockyard. Although most famed for his diary writings that spanned the period 1660–69 he was, like the two Petts, a member of the Navy Board, with Pepys holding the post of Clerk of the Acts. In modern-day speak, this can most closely be translated as secretary, although it should be added that he also had full voting rights on the Board. As such, he did not just handle the paperwork relating to matters connected with the civilian administration of the Navy but could both regulate and advise on a wide range of associated matters. Furthermore, when visiting the dockyard at Chatham, his status automatically meant

that he was accommodated in Hill House, a building that Pepys, in a diary entry for 8 April 1661, describes as ‘a pretty pleasant house’. In coming to Chatham, Pepys was charged with inspecting the efficiency of the yard and to head off any emerging problems. On a number of occasions, and through his diary, Pepys expressed concern at the way Peter Pett was carrying out his duties as Commissioner. In July 1663 he confided:

… being myself much dissatisfied, and more than I thought I would have been, with Commissioner Pett, being by what I saw since I came hither, convinced that he is not able to exercise that command in the yard over the officers that he ought to do.

And, again, in August 1663:

Troubled to see how backward Commissioner Pett is to tell any faults of the officers and to see nothing in better condition here for his being here than they are in any other yards where there is [no Commissioner appointed].

Pepys’ first significant visit to the dockyard was made in April 1661, when he was required to supervise the auctioning of a number of items of ageing dockyard property. Was it a visit designed specifically to keep an eye on how Pett was handling matters, given the various accusations that had been made against his father? Certainly Pepys made a point of viewing ‘all the storehouses and old goods that are this day to be sold’.

Pepys was also present at Sheerness in August 1665 for the planning of a second dockyard to be sited on the Medway:

… and thence to Sheerness, where we walked up and down, laying out the ground to be taken in for a yard to lay provisions for cleaning and repairing ships; and a most proper place it was for that purpose.

28

In time, the dockyard at Sheerness was to take on a subsidiary role to that of Chatham, concentrating on the refitting of smaller vessels, especially frigates. For much of its existence, the yard at Sheerness was also under the authority of the Commissioner at Chatham, rather than the yard having its own Commissioner.

These, as it happens, were serious times, the country going through a succession of trials and tribulations. In the Civil War that had resulted in the beheading of Charles I, the dockyard at Chatham had been relatively little affected, having quickly fallen into the hands of parliament. However, following the Restoration of 1660, the country had entered into a string of wars with the Dutch, these primarily fought at sea. The position of Chatham, located close to the east coast, was of paramount significance, so the dockyard was called upon to undertake the bulk of repair and maintenance work on an increasing number of ships on active service in the North Sea and Channel. However, the Treasury was hard put to support the war, choosing to make economies that were, given the importance of the work being carried out at Chatham, quite suicidal. It was simply decided to delay paying

the workforce their regular wages, with not a penny made available for months on end. In November 1665, Pett was reporting that the men were on the verge of mutiny and there was absolutely no way of disciplining them. Most of the men at Chatham were under-employed, for the lack of money also meant a lack of stores. In November all the workmen in the yard laid down their tools and attended a mass meeting in which they demanded their wages. Further trouble was only averted when a number of the leaders were put into the dockyard stocks before being transferred to prison. With something like £18,000 owing in wages to the men at Chatham, this was hardly a suitable long-term solution and there were a number of incidents in which the men stopped working completely.