Chatham Dockyard (7 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

The tarred yarn, having been allowed to dry and wound on to bobbins, was transferred to the ropewalk. This was a massively long building, 1,155ft (352m) in length.

23

Here was undertaken the final two stages of the rope manufacturing process, that of combining the individual yarns into strands and then the strands into rope. The first process was achieved through the mounting of the bobbins at one end of the floor and attaching the yarn ends to a rotating hook mounted on a wheel frame. The wheel frame, manually powered and mounted on wheels, travelled the length of the laying floor, drawing out yarn from the bobbins and twisting the strands together. Each strand, to prevent theft, had the government mark inserted in coloured worsted through the whole length of the strand, the mark at Chatham being yellow. The final stage, that of ‘laying’ or closing the great ropes, necessitated the strands being laid out along the length of the ropewalk floor, one end of the strands connected to hooks that could be rotated on a fixed point, while the remaining ends were attached to a wheel frame, in the case of small rope, or a larger jack wheel. To both separate the strands, and keep them at a constant height, trestles were placed at intervals between the jack wheel and back frame, removed in turn as the jack wheel moved forward. The hooks, both at the fixed point and on the jack wheel were then turned by manual labour, this twisting the frames to form rope with the jack wheel drawn along the laying floor.

Four basic types of rope were produced on the laying house floor and these were known as cable, hawser, towline and warp. Each was of a different dimension with each performing a specific task on board a man-of-war. Cable, the heaviest, was composed of nine strands laid first into three ropes and then into one large rope. Used to secure the anchors, its circumference varied from a maximum of 20in down to 9in. A 20in cable weighed 7,772lbs and contained 1,943 threads of rope yarn. A 9in cable, on the other hand, was of 1,572lbs and contained 393 threads of rope. According to William Falconer, who wrote his maritime dictionary while employed in the Ordinary at Chatham:

All cables ought to be one hundred and twenty fathoms in length; for which purpose the thread or yarn must be one hundred and eighty fathoms; in as much as they are diminished one third in length by twisting.

24

The method of manufacture for the other three basic types of rope was different, as they were all hawser laid rather than cable laid. This meant that instead of each being of nine strands, as with cable, they were of three strands, with the number of yarns in each strand differing according to the size of rope required. Warp was the smallest, being used to remove a ship from one place to another while in port, road or river; towline was the next smallest and was generally used to remove a ship from one part

of a harbour to another by means of anchors or capstans; hawser was smaller than a cable but larger than a towline, and most frequently used for swaying up topmasts.

A particularly impressive feature of the dockyard was the numerous storehouses, with the largest, 340ft in length, situated on the Anchor Wharf and within the area of the ropery. In addition, and immediately north of the Old Single Dock was a further storehouse of substance, this erected between 1723–24. Three storeys in height and of brick construction, its primary use was that of housing materials that were immediately required in the shipbuilding and repair process. In addition, the ground floor of this building sheltered several sawpits, while in the roofing was a loft used for the laying down of the full-scale plans of ships under construction and known as a mould loft. A centrally positioned clock tower, a useful addition in an age where pocket watches were rare and wristwatches unknown, was centrally positioned on the roof of this building, allowing it to become known in later years as ‘the Clock Tower Building’.

One who was clearly impressed with the various storehouses that were to be found in the dockyard and, as it happens, in the adjoining gun wharf was Daniel Defoe. He paid a visit to Chatham sometime around 1720 and gave particular attention to these buildings, referring to them as like ‘the ships themselves’ being ‘surprisingly large, and in their several kinds, beautiful’. As for what kinds of stores they had been built to accommodate, Defoe goes on to explain that they contained:

… the sails, the rigging, the ammunition, guns, great and small shot, small arms, swords, cutlasses, half pikes, with all the other furniture belonging to ships that ride at their moorings in the river Medway. These take up one part of the place, where the furniture of every ship lies in particular warehouses by themselves and may be taken out on the most hasty occasion without confusion, fire excepted. The powder is generally carried away to particular magazines to avoid disaster. Besides these, there are storehouses for laying up the furniture and stores for ships; but which are not appropriated, or do not belong (as is expressed by the officers) to any particular ship; but lie ready to be delivered out for the furnishing of other ships to be built, or for repairing and supplying the ships already there, as occasion may require.

25

Ollivier, himself, although impressed, did not feel the storehouses at Chatham compared favourably with those in the dockyards of France, considering them to be less commodious. Perhaps he was disappointed by their overall height, with each floor being only about 10ft above the other. Ollivier enquired as to the reason for their lack of height and was informed that ‘there was no reason for any great height in the storeys of a storehouse, it is but wasted space unless it be filled up completely’. He was further told that ‘if it is desired to fill it up then much time is required to stow and remove the stores which can be placed there’.

26

Ollivier also drew attention to differences in practice in the system of storage used at Chatham compared with that in the French dockyards. Whereas in France a ship coming into the dockyard would have all its stores taken off and stored in one place, this was not so at Chatham. Instead, all of the stores of one type were kept together and taken to

individual storage areas ‘with labels on which they write the name of the ship to which they belong’. Ollivier considered this to be wasteful of time, but was informed that if the French method was adopted ‘it would require a greater number of Storekeepers to watch over the stores, since it is their practice here to look after them continuously, to inspect them, to replace those that are spoiled, and to maintain them all in good state as long as possible.’

27

Specifically, he was asked to consider the advantage of keeping ships’ blocks all under the same roof, irrespective of the vessel they came from:

A block maker, for example, is in charge of the block store; he has under his eye all of the blocks of all of the ships, and thus he is able to look after them better and with less expense than if they were dispersed among different storehouses; and likewise for all other stores.

28

Unfortunately Ollivier only gives limited attention to the Ordinary, which was geographically centred on the river. Here were the moorings that were set aside for ships laid up when out of commission. Placed under the authority of the Master Attendant, the principal officer of the Ordinary, were the various ship keepers who had been placed on board each of the vessels held in the Ordinary, together with the sail makers and riggers, those whose work brought them in closest contact with the moored vessels. As each vessel entered the Ordinary, a process most commonly witnessed at the end of a period of hostility, it would have its masts, sails, rigging and guns removed. The ship keepers, who would normally already have been part of the ship’s crew, being attached to a vessel for the life of that vessel, were the gunner, boatswain, carpenter, purser and cook. Each had a specific duty and was supposed to ensure that the vessel remained in a watertight condition and ready for a return to service in the event of mobilisation.

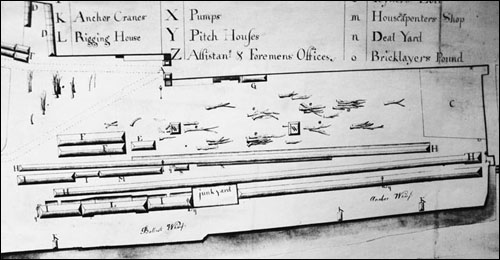

Detail of a plan of the yard that dates to the time of Blaise Ollivier’s visit. The buildings to be seen are mainly those of the ropery that had been built in the previous century. Of particular note is that of a separate spinning and laying floor, these later to be combined into one building. Note the rather haphazard storage of timbers, a point noted by Ollivier in the account that he later wrote.

At this time, the Ordinary at Chatham had somewhere in the region of fifty moorings, each vessel positioned according to her draft and depth of water available.

29

Referring to the cables used in the mooring of these vessels, Ollivier indicates that each vessel was:

… moored with but a single cable [and] made fast to an iron mooring chain lying on the bottom; they also have a stream anchor at the ship’s side or hanging from the cathead ready to let go should the mooring cable fail.

30

A mooring, at this time, to expand on Ollivier’s remarks, consisted of two anchors, fixed on opposite sides of the river, with a chain extending between them. In the middle of the chain was a long square link, its lower end terminating in a swivel attached to a bridle. From this bridle stretched a rope cable that was drawn into the moored ship by way of its mooring point.

It has already been noted that the Medway was subject to increased shoaling, but it is not a point mentioned by Ollivier. During the sixteenth century, when the Medway was first used for the harbouring of ships, the entire Tudor Navy could be located in this single river. However, as ships increased in size, the Medway proved a less attractive proposition. A map of 1685 shows eight first and second rates moored in the river, together with fifty third rates. Moving forward to 1774, a subsequent map of the river indicated sufficient depth for only three first and second rates and five third rates. Partly, the problem was that of silting, but an additional factor was an increase in the size of warships and the depth of water they required. In the 1680s, most first rates moored in the Medway would not have exceeded 1,600 tons but by the time of Ollivier’s mission, the larger ships usually weighed in at 1,800 tons or more.

An examination of the Ordinary, together with some of the ships held at moorings in the river, marked the completion of Ollivier’s espionage mission to Chatham. Already he had visited the yards at Deptford and Woolwich and while at Chatham, possibly on Thursday 4 May, he also visited the yard at Sheerness. Finally, and before returning to London, he visited the yard at Portsmouth. As for the rapidly expanding yard at Plymouth, this he was unable to fit into his itinerary. His final task before leaving England was that of carefully writing up his notes ready for these to be handed over to Maurepas upon his return to France.

It was not, however, until January 1738 that Ollivier was finally able to return to Brest, where he was returned to his old office of Master Shipwright. As well as spying on the dockyards in England, he had also been given the task of supplying a similar report on the dockyards of the Dutch Navy, requiring him to spend several months in the Netherlands. Doubtless Ollivier would have been destined for great things if it had not been for his contracting tuberculosis, resulting in his premature death on 20 October 1746. However, during those final nine years of his working career, he was responsible for overseeing the design of several significant warships, while also ensuring that the dockyard at Brest was given additional dry docks, this resulting from his observations at Chatham and his view of their usefulness in the graving of ships.

3

T

HE

V

IEW FROM THE

C

OMMISSIONER’S

H

OUSE