Chatham Dockyard (29 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

As noted by the

Chatham News

, work had begun on the two other basins as well as the second pair of dry docks. It was in November 1872 that the No.8 Dock was finally

completed, with the No.9 Dock completed in 1873. Next was the No.2 Basin and finally, in 1883, the No.3 Basin. It was this latter basin that also provided a primary entry into the Medway, this through the caisson gates of the Bull’s Nose – so named because of its shape. Although in this later construction work continued use was made of convict labour, the savings were not as great as had originally been expected. For this reason, much more of the work on both the Nos 2 and 3 Basins involved a large proportion of contract labour, with the employment of convicts subsequently reduced.

One particular attempted financial saving that did pay off, was the reuse of several buildings from the dockyard at Woolwich. Indeed, the fact of this dockyard, together with that of Deptford, having been closed in 1869 was a direct result of the expansion of facilities at Chatham, it no longer considered necessary to retain these two yards on the Thames given that they would also have needed a considerable updating of their facilities. In the case of Woolwich, two slip covers were identified as of future value to Chatham, these being iron-framed structures that could be taken apart and reassembled. In their subsequent life at Chatham, they were to serve as Boiler Shop No.1 and Machine Shop No.8, both reassembled alongside the No.1 Basin. While the cost of constructing such buildings can only be guessed at (it was probably in the region of £20,000–30,000), the amount needed for their removal and re-erection was a mere £6,000.

13

Once completed, the extension works totally revitalised the dockyard, allowing the refitting of a greatly increased number of ships while encouraging the Admiralty to use Chatham for the building of numerous additional battleships. This, of course, led to a considerable increase in the dockyard workforce. Whereas in 1860 the number employed had stood at 1,735 it had, by 1885, and completion of the extension works, reached over 4,000. Of the ships built at Chatham, each class of battleship was larger than its predecessor. In

1875 Chatham launched

Alexandria

, the largest ship by that date to have been built in the yard. Displacing just over 9,000 tons, it exceeded by nearly twice the tonnage any vessel previously built at Chatham. Yet, not ten years later,

Rodney

, displacing over 10,000 tons, was launched. Others followed in quick succession. Fourteen thousand tons had been reached by 1891 with the launching of

Hood

, followed by the 15,000-ton

Venerable

in 1899.

The construction of one vessel,

Magnificent

, is associated with an experiment that had less to do with ship design and more to do with the ever more important panacea of financial savings through increased speed and efficiency. As a result of a report issued in 1888 by a committee established by parliament to look into the management of the home yards, it was revealed that idleness within sections of the workforce was ‘practically unchecked’. In particular, reference was made to the practice of ‘keeping crow’, whereby a look-out was kept for supervisors while the rest of the gang idled. As for the inferior officers, the ones directly appointed to supervise the gangs, they were considered to be ‘either apathetic or too much in the hands of the men’ while the superior officers were found ‘to be powerless’. The Admiralty reacted by introducing a few poorly thought out ideas, which included the removal of a number of less competent and ageing inferior officers together with the introduction of chargemen, promoted workers who were to ensure that those they worked with were fully employed. In addition, a newly devised method of payment by results, this time known as ‘tonnage payments’ was also temporarily adopted, with each man paid according to the weight of the material built ‘into the whole of a section of a ship’. However, as the majority of those employed in the yards worked in gangs, it was

impossible to reward individual output. As a result, tonnage payment, which had not noticeably increased work output, was rapidly abandoned.

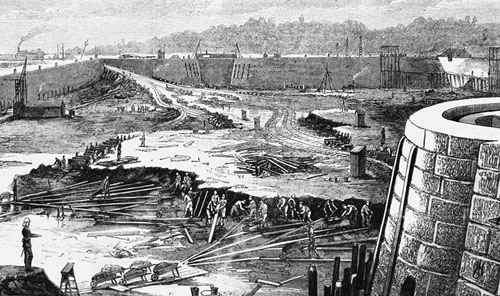

An engraving from

The Graphic

, dating to December 1871, showing excavation work being undertaken on the No.2 Basin. Viewed from the south-east, work is very much in a forward stage, with much of the depth of this 20-acre site having already been reached. The similarity between the engraving and the dockyard model are remarkable and suggest that either the model was based on this engraving or that both the model and the engraving were executed at a more or less identical point in time.

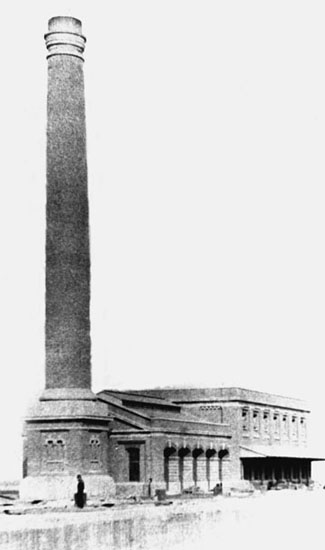

One of the last of the buildings belonging to the extension to be completed was that of the lock pumping station that stood between the North and South Lock on the Bull Nose. The distinctive chimney immediately adjoins the Boiler House with the Engine House distinguishable as the raised part of the building furthest from the camera. Following the closure of the Upnor Gate, that gave access into the No.1 Basin, the two locks were the only means of bringing warships into the three basins and were regularly pumped to ensure a safe and easy entry and exit.

Undoubtedly the Admiralty was hamstrung by its own parsimony. If the workforce was to be motivated into increasing its output then the rewards, however allocated, would need to be of a sufficient level. Indeed, there was much evidence to suggest that those employed in the naval dockyards failed to work harder because they believed their pay to be inadequate. Should the Admiralty choose to correct this, so that wages reflected the private yards where the average wage was sometimes 30 per cent greater, then levels of efficiency might improve.

Given that the Admiralty was ill-prepared to increase wage levels to those found in the private yards, the Board decided upon a more imaginative approach. It would institute a race in which two identical ships, one at Chatham and one at Portsmouth, would be laid down together. Using the age-old rivalries that existed between these two yards, those building the ships would be encouraged into a maximum effort. To ensure fairness, those managing the two yards were given a completely free hand in deploying the workforce. Indeed, the only stipulated condition was that the two ships should be completed in as short a time as possible.

For Chatham, the race officially began on 18 December 1893 when the keel of

Magnificent

was laid down. She was a ‘Majestic’ class battleship that would eventually displace 14,900 tons. Meanwhile at Portsmouth, just twenty-eight days later, the name ship of this class was also laid down, with the intervening period having been used to prepare some of the plates and frames that were needed for her construction. In itself, this had marked an interesting departure from normal shipbuilding practice, it having previously been reckoned more efficient to carry out all construction work wherever the keel was

to be laid. In the light of this venture, which made considerably better use of facilities at the dockyard, other ships were also to have preliminary work performed upon them prior to the official keel laying. At Chatham, meanwhile, everything was moving forward with great rapidity. In the same week that

Majestic

’s keel was laid, it was confidently reported:

The construction of the

Magnificent

is being pushed, and already the frames amidship have been put in place to the height of the armour deck.

14

However, it was not long before similar reports were made on the progress of

Majestic

, with this vessel having possibly overhauled

Magnificent

in early May. At least this was the optimistic assumption made by the Portsmouth correspondent of

The Naval and Military Record

:

The

Majestic

at Portsmouth is now 400 tons ahead of the

Magnificent

at Chatham, and instead of floating her out next February, the officials hope now to celebrate that event this side of Christmas.

15

It appears that the two ships continued neck and neck for much of the rest of the year, with both superintendents allowing a huge proportion of yard workers to attend to their respective charges. At Chatham, in September, it was reported that 1,200 were employed upon

Magnificent

and that the vessel was ‘completely plated from stem to stern’. Furthermore it was indicated that the engine contractors, Messrs Penn, would soon commence work on the fixing of her engines. At Portsmouth meanwhile, the first indication of a serious problem was just emerging:

A modern-day view of the No.1 Basin, which officially opened in June 1871. To facilitate its use for the repairing of ships, it had a total of five dry docks leading away from the basin. Of these, the No.5 Dock, originally known as the Invincible Dock, can be seen immediately to the right. It was so named because the first vessel to enter this dock was the ironclad battleship

Invincible

. With such a grand name for this historic feature, it seems unfortunate that this is not recognised within the Chatham Maritime development.

An unexpected delay has occurred in the delivery of the armour plates for the

Majestic

, and this may prevent the floating of the ship out of the dock early in December.

16

This was only seen as a temporary setback, with twenty-one gangs, besides other trades, working on

Majestic

by the end of November. By then, so it was estimated,

Majestic

had 5,335 tons built into her while

Magnificent

could only boast 5,140 tons.

However, the delays in the delivery of armour plating were proving problematic. At Portsmouth there was increasing concern that Chatham would eventually win the race, not through greater effort, but as a result of contractual delays. It appears to have been a subject of much comment for, while there was only one contract for

Magnificent

’s armour plates, the

Majestic

at Portsmouth had two suppliers. This, so it was felt, gave Chatham an advantage, orders for this yard being fulfilled with greater promptness. In fact, it even appears that Chatham was managing to acquire armour plating that was destined for Portsmouth. Of this episode, Lord Charles Beresford, then Captain of the Steam Reserve at Chatham, later wrote:

During 1893–4 the

Magnificent

was being built by Chatham in rivalry of Portsmouth, which was building the

Majestic

. It was becoming a close thing, when the

Magnificent

received from the manufacturers a lot of armour plates which might have gone to the

Majestic

, and which enabled us to gain a lead.

17