Chatham Dockyard (25 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

At this stage, however, the main component of a ship, even if it was given steam machinery, was still timber, with the frame and planking laid along the side of this material. Shipwrights, therefore, still predominated and took charge of all ships while under construction. However, developments in gunnery and the arrival of the explosive shell required that warships should be considerably strengthened against such an onslaught.

13

At first, this need was restricted to ships that would operate in-shore and close to the heavier guns that were usually associated with harbour defences. It was a requirement that was spurred by events in the Crimea with ironclad floating batteries specifically built for the conflict that spanned the period October 1853 to February 1856. One such ship was

Aetna

, constructed at Chatham and launched in April 1856. As such, she was the first armoured vessel built at the dockyard, possessing a timber hull that was clad with 11.4cm iron plating.

The work performed on

Aetna

placed Chatham on course for the next great revolution in warship construction, building ocean-going armoured battleships that would soon entirely replace their unarmoured, wooden-hulled predecessors. First to develop such a vessel were the French, with

La Gloire

launched at Toulon in November 1859. Designed by the French naval architect Dupuy de Lôme, she was a 5,630-ton broadside battleship with a timber hull of 43cm in thickness covered over with the addition of 12cm-thick iron protection plates. To this extent she was similar in some respects to

Aetna

, in that she was clad in iron rather than her hull being constructed entirely of metal and her outer cladding having only a limited backing of timber. Through

La Gloire

, the French gained an initial lead in the construction of such vessels. Britain, having both a greater level of available resources and being more technically proficient, soon overtook the French with the launch of

Warrior

. She was a vessel that was not only twice the size of

La Gloire

but outclassed her in both speed and gunnery while also having a fully armoured hull that supported an 11.4cm armour belt with a 43.2cm teak backing. Built by the Thames Iron Shipbuilding Company, two further ‘Warrior’ class broadside ironclads were also launched that same year and from privately owned shipyards, namely those of Robert Napier in Glasgow and Palmer Bros of Jarrow.

Construction of the hull of a warship either on a slipway or dry dock was only part of the work that was undertaken on new warships by the artisans of the dockyard. Once launched she had to be fitted out, with dockyard workers here seen employed upon the fitting out of

Euryalus

, a steam frigate launched at Chatham in October 1853.

For Chatham and the other royal dockyards, all this was proving something of a threat. If such vessels were only to be built within the private sector, the value of Chatham and the other naval yards would quickly diminish. Indeed, a degree of pressure was beginning to emerge for these yards to be either closed or seriously reduced in scale, it being suggested that the largely privately owned yards would be much more adept at meeting the needs of the Navy. Among those who took this view was Patrick Barry, a London-based naval correspondent, who went so far as to suggest in 1863 ‘that we [Great Britain] cannot ever be possibly strong under the existing system’ and that upon ‘the lifeless dockyards the treasure of this great country is poured out in vain’. His particular solution was a ‘complete overthrow of the whole system’ and its reorganisation on commercial principles.

14

This was something against which the Admiralty fought, aware that the naval dockyards came significantly into their own during times of war. It was at such moments that a naval yard could be quickly mobilised and the necessary ships rapidly put to sea. If reliance, instead, was placed on dockyards organised on a profit motive basis, it seemed unlikely that such facilities would be so readily available, the existing facilities simply unable to meet the new demand. Admittedly, the royal dockyards might be under-utilised during times of peace, but that was because of a proportion of their resources being on standby for a sudden (and sometimes totally unexpected) outbreak of war.

To ensure that the royal dockyards did not continue to be overshadowed by the private yards, an important experiment was put in hand. It was decided that two very different vessels should be built and both fully incorporating the use of iron. Moreover, it was Chatham, due to the skills already developed and a sufficiency of available space,

that was chosen to undertake this work. The first of these was

Royal Oak

, a conventional ninety-gun warship that had been radically redesigned while in frame, to facilitate the addition of iron cladding. The second was

Achilles

, the first true iron-hulled battleship to be launched in a royal dockyard.

Royal Oak

was officially ordered by the Admiralty in April 1859, with her keel laid thirteen months later. For

Achilles

, the lead time was not quite so extensive, for she was ordered in October 1860 and her keel laid six months later. In neither case was it possible to start immediate construction as a considerable amount of preparation had to be undertaken. If nothing else, a considerable amount of new machinery had to be brought to the dockyard, this included specialised bending, cutting and drilling equipment. However, little of this would have been of value for construction of one of these vessels,

Achilles

, if it had not been for an earlier lengthening of the No.2 Dock and completed in October 1858. In itself, this had been necessitated by the increasing size of ships with this dock subsequently selected for the construction of

Achilles

. Despite being the largest dry dock in any of the naval yards, having a length of 395ft, she was still not of quite sufficient length for the new ironclad, with the altars at the head of the dock having to be cut away prior to the keel of the new ship being laid. It was a point picked up by Patrick Barry, who claimed that the dock was still not of an adequate size, with her construction undertaken ‘in a dock barely large enough to hold the ship’. According to Barry, who was writing while construction of

Achilles

was underway, possible defects in the construction of this ship were being concealed by the dock providing a glove-like fit:

Few care to undertake the descent to the bottom of the dock, and of that few, not many are disposed to pursue knowledge under circumstances so embarrassing and filthy. Going down in a diving-bell to the foundations of Blackfriars Bridge is on the whole a more inviting undertaking than going down to the lower part of the

Achilles

among the blocks, props, smiths’ fires, ashes and other things below.

15

In addition to the ordering of machinery, working sheds had to be erected for its accommodation with this including the conversion of the No.1 Dock into a giant covered workshop. Here, metal plates were to be assembled with these transferred to where the two ships were being built by means of a newly installed tramway. As a completely new venture for the dockyard, work upon

Achilles

, not unnaturally, did fall behind. Constantly the delivered iron plates had to be rejected, failing to meet the high standards demanded by the Admiralty. Yet every effort was made to maintain the most rapid building pace possible. All other work in the dockyard was frequently brought to a standstill, absolute priority given to the two ironclads. If shipwrights were unable to be employed upon one ship, they were simply transferred to the other. Such was the situation in February 1862 when the majority of shipwrights were engaged upon the building of

Royal Oak

. According to the

Rochester Gazette

, ‘the officials of the yard being apparently determined to spare no effort in order that she may be as far as possible advanced by September, the time fixed for launching her.’

16

Interest in progress upon these two vessels was by no means restricted to the local press, with both national and specialist newspapers and journals also keen to report progress on their construction. Some two months after the previously quoted

Rochester Gazette

report, the

Illustrated London News

was in a position to inform a much more geographically dispersed readership:

The construction of this gigantic iron frigate [

Achilles

], under the superintendence of Mr O.W. Laing, the Master Shipwright of Chatham Dockyard, is proceeding with the greatest rapidity towards completion: the vessel is nearly in frame, and the progress day by day is something wonderful. The

Royal Oak

wooden frigate of 51 guns is now ready for plating; and the forward state of everything in connection with the new fleet at this establishment reflects the highest credit on all the officials connected with it. The stem of the

Achilles

is a splendid specimen of iron forging; it was furnished by the Thames Iron and Shipbuilding Company, the builders of the Warrior &c., and weighs upwards of twenty tons.

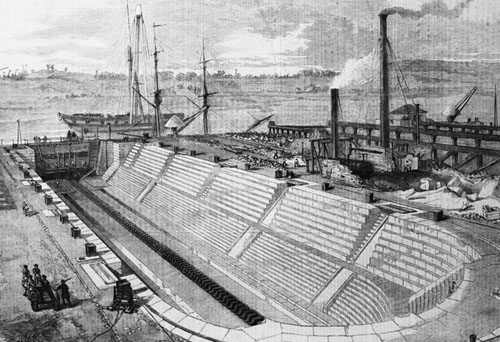

Reopening of the No.2 Dock, as depicted in the

Illustrated London News

of 13 November 1858. Work on lenghening this dock was commenced in October 185 and completed in Ocotber 1858. The work was carried out by Messrs J. and C. Rigby, from the designs of the director of engineering and architectural works of the Admiralty. The dimensions of the dock were:

| Length from the caisson on the coping | 395ft |

| Length on the floor from caisson to head of dock 3 | 60 |

| Depth from coping to floor | 31 |

| Width on the floor | 30 |

| Width between coping | 85 |

The dock was to prove an important addition to the yard at Chatham as, without this extended dock, it would not have been a possible for

Achilles

to be laid down just three years later.

The projected launch date for

Royal Oak

, early September 1862, was indeed met, with this vessel entering the Medway on the tenth of that month. The

Rochester Gazette

duly reported this important event:

As this was the first launch of a vessel of this class from Chatham dockyard – and in fact from any of the royal dockyards – great interest has been excited by the event … An immense staging was erected in the head of the slip; it was tastefully decorated with flags. Admission to this was only to be gained by ticket … At half past one o’clock labour was suspended in the Yard, and already a large crowd was greatly increased by the flocking to the spot by hundreds of workmen.

17

Once launched, and having a length considerably less than

Achilles

, she was transferred to the No.3 Dock where she was comfortably received. Here, she was fitted with an 800hp engine supplied by the Henry Maudslay Company, with

Royal Oak

finally completed in April 1863.

With the launching of

Royal Oak

, a large proportion of the workforce was transferred to

Achilles

, with 1,300 eventually employed on this one ship. As new processes were involved, the Admiralty had been forced to engage an even greater number of ironsmiths together with an increased number of boilermakers. In particular, the ironsmiths were called upon to train some of the existing dockyard shipwrights into the skills needed for the construction of these new-style ships. This was regarded by them as unacceptable with about ninety ironsmiths downing their tools shortly after lunch on 3 July 1863. They also complained they were not getting a promised advance in their pay. A basic account of the event that followed was later given in a pamphlet memorialising the life of John Thompson, a Chatham dockyard shipwright, and reproduced by the

Chatham News

in May 1893: