Chatham Dockyard (28 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

By a judicious method of employing the convicts, and one, which I believe may without difficulty be introduced; the whole scheme, large as it may appear, may be carried out to completion within a moderate time, and at a small cost.

6

And to this he further added:

What appears to be wanting are a general system of mechanical management and a method of qualifying men and applying their labour to duties for which they are practically qualified.

The general management as regards the discipline of convicts will necessarily require being under the control of the convict department but the direction of the men in the execution of their duties may, I imagine, be under the control of this department [Engineering and Architectural Works].

This being established, a method should be adopted for raising the men from a state of worthlessness to useful labourers, from labourers to artificers, and from artificers to leading men. I most successfully adopted a similar method for qualifying men for executing difficult engineering and other works of great magnitude at a foreign station; and some years ago prepared a form for the guidance of officers in accomplishing the same object with convicts at Gibraltar and Bermuda, and which is still successful in use.

7

Scamp, over a long period of time, gave attention to how the facilities at Chatham might be adapted, giving particular attention to layout and efficiency. In 1849 he put forward a fairly revolutionary concept that would not only have considerably reduced the time taken in preparing a ship for the Ordinary but also completely reduced the reliance of the dockyard upon the river as a working area. In essence, it involved the construction of a camber, where masts and other furnishings would have been removed, with the vessel then raised and moved to a dry berth and secured for the length of time it was to remain in the Ordinary. It was not an idea pursued by the Admiralty, it being feared that in lifting and transporting the vessel, damage would be inflicted on the structural integrity of the vessel.

8

As for the extension that was to be built at Chatham, it was initially intended that it would simply provide the dockyard with a few additional docks and slips, these to be built upon the land that had been acquired on St Mary’s Marshes where it immediately adjoined the existing yard. By the mid-1850s, these initial thoughts were accompanied by the possibility of constructing an enclosed basin in which warships built at the yard could be more efficiently fitted out and completed, rather than this being undertaken in a mid-river position. Scamp, who in association with Col G.T. Greene, his immediate superior, carried out much of the original design work, in producing an important discussion document in January 1857, was concerned that in setting out to provide Chatham with such an enlarged new facility, ‘ample basin space’ should be provided, this being ‘useful at all times but essentially necessary to meet the demands of a great war’. Scamp noted:

At Deptford some basin space is being added while at Woolwich the basin space was twice increased. After the works were commenced at Sheerness, much more basin space [was and still] is required. At Portsmouth though, 100 feet was added to the breadth of the basin during the time the works were in progress, yet this establishment is still deficient in basin space. At Devonport the basin will chiefly be used as a boat basin and at Keyham a suggestion that I made some years ago for increasing the north basin from 700 to 1000 feet, was approved from a conviction that more basin space would be required. Having all these examples, it would be a great misfortune should another mistake be made at Chatham.

9

Indeed, it was eventually settled upon Chatham having 67 acres of water enclosed by these basins, this considerably in excess of that existing in all of the other yards combined. In design, they were to follow the length of the creek that had once separated St Mary’s Island from the mainland, with a total of three being built and interconnected. The influence of Scamp is clearly discernible. In all of his major design undertakings, Scamp had looked at efficiency savings through the creation of properly integrated work spaces. In laying out these basins, each was to have a specialised role that hinted at a production line process. Once launched, or floated out of dry dock following underwater repairs to the hull, a vessel would be released into the No.1 (or repairing) basin for the completion of work upon her upper deck before being taken to the No.2 (factory) basin for the installation or repair of machinery and boilers. Finally, the vessel would be moved to the No.3 (fitting

out) basin for rigging, coaling and the mounting of her guns. Surrounding each of these basins were the various factory buildings, storehouses and workshops that were necessary to support the dedicated tasks undertaken upon ships brought into each of these basins. As for the repairing basin, on its south side there were four graving docks, each 420ft in length, with 28ft 6in over the sill at high water neaps, and 31ft 6in at high water springs.

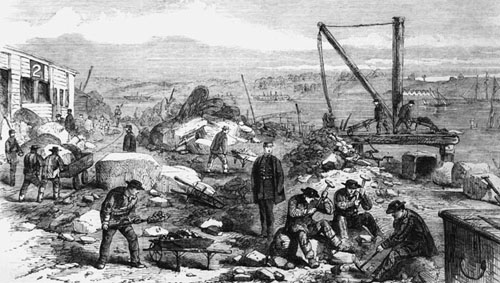

Before work could begin on the extension, convicts were first employed on construction of both the prison that would house them and construction of a masonry wall that would surround St Mary’s Island. Here, in this engraving from the

Illustrated London News

of March 1861, convicts are employed on the carriage and breaking of stone for the sea wall.

Before any of these works could begin, not only had much of the land on St Mary’s Island to be purchased but a further Act of Parliament had to be passed to allow the Admiralty the right to both acquire and block from public use the creek that separated St Mary’s Island from the area currently occupied by the dockyard. This was duly brought before parliament during the summer of 1861 and, in particular, dealt with the need to compensate the Mayor and Aldermen and Company of Free Dredgers of the City of Rochester for the destruction of the fishery in the creeks. While the area of the planned extension had first been marked out in December 1860, construction work could only begin during the following year when the new Act had come into force. To begin with, and not unnaturally, this was construction of a river wall and embankment, this having an estimated cost at that time of £85,000. Whether that particular cost was adhered to is uncertain. But more definite was the fate of the overall estimate for the entire project, this standing at £943,876 at this particular point in time. By 1865, the overall cost had risen quite steeply and was then being estimated at a final figure of £1.25 million. Even this figure was to prove hopelessly inaccurate, with the final cost of the project reaching in excess of £2 million.

Not surprisingly, given that it ensured the future of Chatham dockyard, and would bring a great deal of work and prosperity to the area, the

Chatham News

was in a celebratory mood when plans for the extension were publicly announced in November 1860:

This is an important fact for our Towns. An augmentation of our Dockyard must, in the first place, cause a great increase in the amount of employment, and sensibly swell the amount of expenditure of various kinds in the Towns. With an enlarged Dockyard must come increased employment for officers, clerks, artificers, labourers; a larger demand for residencies, increased trade, augmented prosperity for the locality. It is believed that these Towns are making an advance in almost every direction; and this scheme, if carried into effect, will give a great impetus to that progress.

To this was further added the comment:

Though, unfortunately, of late the Towns, in common with most places, have suffered from the generally depressed state of trade, and the failure of a Kentish staple – hops, and though they will, like other towns, feel the effects of the short harvest, we may reasonably expect that, from the greatly increased Government expenditure – a kind of expenditure on which the locality must greatly depend at all times – which we may look for in the future we may safely prophesy a large increase in the prosperity of our Towns.

10

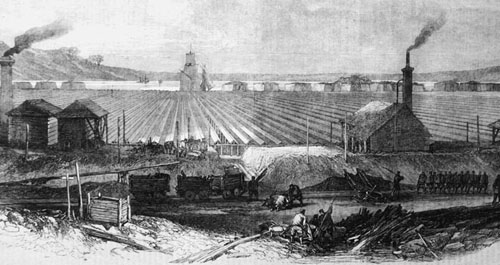

During the 1860s, the island site was completely drained and then built up an additional 8ft, with sure foundations being dug for the numerous projected buildings. This was all carried out by convict labour, with over 1,000 employed on the site. Another task given to the

convicts was that of preparing and then operating a 21-acre brick field built at the north end of St Mary’s Island. This produced most of the bricks used in the extension and is said to have been responsible for the manufacture of 110 million bricks by March 1875.

Not surprisingly, in constructing the mid-Victorian dockyard extension that was built at Chatham, a massive amount of material was required. Not least was the need for bricks, with more than 110 million having gone into its construction within the first ten years of the project. For the most part, these bricks were manufactured on site, a further task being undertaken by convicts. This

Illustrated London News

engraving from April 1867 shows the brick field on St Mary’s Island and which had, during that year, produced 10 million bricks for the works that were then underway. The first brick had actually been produced in March 1866, the convicts having first drained and levelled a 21-acre site of marshland before installing six brick-making machines that had been supplied by the Atlas Works in London.

The first phase of the extension was completed in 1871. At that time two of the dry docks were complete, while in June of that year the No.1 Basin was officially opened. This was the basin immediately opposite Upnor, designated as the repairing basin, and built with an entrance into the river Medway. The entrance, sealed by caisson, separated the two bodies of water. As part of the opening ceremony, the ironclad

Invincible

, built at the Napier yard a few years earlier, was brought to Chatham to demonstrate the advantage of the new basin, with the

Chatham News

duly reporting the event:

As she passed through none who saw her grand and graceful proportions – her deck alive with officers and men – but must have admired the spectacle. The great ship had her course turned when she had entered the basin, and she proceeded towards the No.1 Dock [sequentially the No.5 Dock]. In short time with hauling and very slow steaming, she was got safely into the No.1 Dock where she will undergo repair. The dock will henceforth be ‘the Invincible Dock’. The fine ship having been placed in dock, the caisson to close its mouth was placed in position, and preparations made for emptying the water in the dock – a process which at present takes a considerable time, as there are only temporary engines for the dock; hereafter all the docks can be emptied in four hours by the powerful machinery to be provided.

11

In its comment column, the

Chatham News

carried a further item, this continuing to extol the virtues of the extension scheme:

Those who do not love Chatham, or who have a jealousy of her have been ever ready to prophesy that the new dockyard must be a failure – that the works created must tumble in – that if the basins and docks were made ships could not get up the river to enter them, and so on. Well – a grand basin, 21 acres in area, with a depth of 33 feet of water, has been successfully constructed; ships have steamed through it; a fine ironclad vessel with her guns etc., on board, has safely come up the Medway, has passed through the wide and deep entrance of the uppermost basin, has traversed the basin, and is now in one of the enormous graving docks which abut on the basin, another dock is ready to receive the largest ship in the Navy; many ships of the first class could lie in the far stretching basin. This much HAS BEEN accomplished. There have been difficulties but they have been overcome. At no distant period a second basin of nearly the same size will be completed. The two great docks in hand will be finished rather later – a glance at these in their present state impresses one with the magnitude of the work, and proves how much time must necessarily be occupied in carrying it out.

12