Chatham Dockyard (31 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

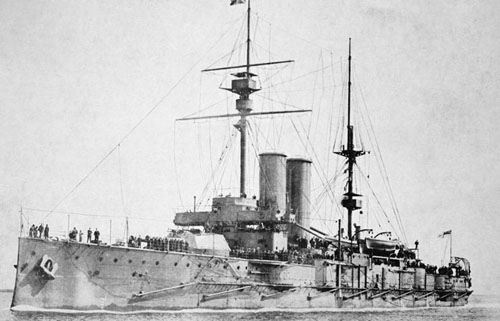

When this photograph first appeared in the

Navy and Army Illustrated

in August 1899 it was entitled ‘a busy scene at Chatham’. What it shows is the return of naval ships to the dockyard following an exercise, with various stores having to be offloaded while seamen are readying themselves for a spot of shore leave.

Africa

, the last battleship built at Chatham and launched from the No.8 Slip on 20 May 1905. While the dockyard had once specialised in the construction of battleships, the arrival of the ‘dreadnoughts’ and ‘super-dreadnoughts’ resulted in Chatham transferring the major part of its skills to the construction of submarines.

A new specialism soon followed – that of submarine construction. In all, a total of fifty-seven were to be built, with the last, an ‘Oberon’ class patrol submarine for the Royal Canadian Navy, launched in September 1966. First to be built at Chatham were four ‘C’ class vessels,

C17, C18, C19

and

C20

. Of a somewhat crude design when compared with submarines launched later in the century, they were of a mere 290 tons and carried a crew of only sixteen in number. Much more significant, and in keeping with the pioneering work usually associated with Chatham, they were the first submarines to be built in any royal dockyard, with the first of these,

C17

, launched from the No.7

Slip on 13 August 1908. From the Admiralty’s point of view it was important that some of these craft should be built in their own naval yards, this to ensure that a check could be kept on the charges made when they were built in the private yards.

While submarines, especially those built prior to the First World War, may not have had the glamour of the large battleships and cruisers, the planned entry of

C17

into the Medway was still enthusiastically covered by both local and national newspapers, excitement fostered in the latter by a supposition that the launch was being conducted in a shroud of secrecy. The

Chatham News

, with its greater experience of reporting ship launchings at Chatham, attempted to put the matter into a broader context:

The so-called moonlight launch of a submarine from the slipway at Chatham yard caused quite a commotion in the London Press, which appeared to have overlooked the fact that submarines were built at this port. As for the secrecy, this has been strictly observed at all the launches of submarines from the slips of private firms, whereas, at Chatham, the workmen employed in building them are bound to secrecy.

1

After the launch,

C17

was taken to the No.2 Dock where she was fitted with engines and other machinery, all of which was constructed at Chatham. In September the

Chatham News

was reporting:

A turn of the century view of the colour loft and where a number of the ‘ladies of the colour loft’ are to be seen engaged in making flags for naval warships. Employing roughly twenty women, they typically produced in any one month some 1,200 flags of different size and purpose. This and the ropery were the only two areas within the dockyard, prior to the outbreak of the First World War, where women were employed.

The first two of the four submarines being built at Chatham, will be ready for trials in a few weeks, probably, and there will then be an opportunity of comparing the Dockyard work on this kind of vessel to that done by private firms. Chatham Dockyard was entrusted with the first pair of this type of craft to be built in the Royal Dockyards and apparently the Admiralty are quite satisfied with the progress that has so far been made, as a second pair of similar craft have been put in hand, and will no doubt be pushed forward as fast as possible.

2

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 not unnaturally had a considerable impact on the yard at Chatham. Most obviously was the massive amount of new work directed to the dockyard, this resulting in the need to rapidly expand the existing workforce, with the number employed reaching 11,000 by November 1918. One way this was achieved was through the employment of women on tasks for which they had previously been thought incapable. On entering the yard, the newly recruited female workers were trained to undertake very specific tasks rather than the broad range normally acquired by an apprentice.

In contrast to those newly entering the yard to undertake the essential tasks associated with warship construction and repair were some of those already employed in the yard and who wished to enlist. If they were part of the established workforce they simply were not allowed to do this, the Admiralty wishing to retain their skills for the duration of hostilities. Some did so, but in so doing, they immediately lost their entitlement to a future pension and readmission to the yard at a later stage. Given this situation, it is not surprising that many of those employed in the yard were embittered by criticisms laid against them for not taking up arms. The

Daily Sketch

for instance, in December 1914, openly suggested

that such workers, in failing to enlist, lacked patriotism. A remark clearly resented by those employed at Chatham, it naturally elicited an angry response from the central committee of the General Labourers Union. An apology was demanded from the

Daily Sketch

, it being pointed out that many of those employed in the dockyard had actually been refused the right to enlist. It was further pointed out that some had still left to join the Army, but in doing so forewent both a relatively secure job and a future pension.

3

Following the ending of the First World War there was considerable jubilation, with the Anchor Wharf Storehouse suitably bedecked with flags to celebrate the Armistice on 11 November 1918.

Certainly there was no shortage of work for the dockyard during those wartime years, with the yard responsible for the launch of twelve submarines and two light cruisers. Looked upon with special pride was the forming of

Zubian

, a tribal class destroyer that had begun life as two separate destroyers;

Zulu

and

Nubian

. In late October 1916

Nubian

had seen most of her bow section destroyed when she had been torpedoed off the Belgian coast while

Zulu

had lost most of her stern when mined in the Dover Straits in November of that same year. Both ships being of the same class, it was decided to join the two between the third and fourth funnels, a task completed at Chatham by June 1917. Another major task undertaken was that of preparing a number of ships for the Zeebrugge raid of April 1918. Designed to strangle both Ostend Harbour and the Bruge canal at Zeebrugge through the sinking of several block ships, Chatham undertook work on six of the ships. On the cruiser

Vindictive

, to be used to land marines, additional armament was put in place, including howitzers, mortars and flamethrowers. More significant was work carried out on five block ships,

Thetis, Iphigenia, Intrepid, Sirius

and

Brilliant

, with each first gutted and filled with 1,500 tons of concrete. Lesser alterations were carried out on other ships, including the placing of explosives into submarines

C1

and

C3

.

A flavour of the intensity and urgency of work being undertaken in the yard during these wartime years was provided by R.C. Lockyer, in a subsequently published essay. First joining the yard in 1916 as a sixteen-year-old rivet boy, he began his working life in the No.8 Slip where

Hawkins

, name ship of a light class of cruisers, was under construction and not to be launched until the following October. The job of a rivet boy was to heat the rivets in a portable furnace before it was placed in a hole already drilled into the armour plate and then hammered by a riveter using a pneumatic riveter. As Lockyer explained, ‘thousands of rivets were used’ with ‘many teams of workers employed’. It is his observations of the yard at this time that gives his essay a particular value, recording the everyday detail that is often lost over time. Of the yard in general at this time, he refers to being ‘amazed’ by the many sights he witnessed:

Many of our ships were either sunk or damaged and lots of the latter were brought to Chatham for repairs. They were terrible sights when they either crawled into the basins or, more often, had to be towed in. The more badly damaged vessels were got into dry dock as soon as possible, some in fact nearly sinking.

Of one cruiser, which he fails to name, and returned to sea following repair to extensive torpedo damage, he recalls that within 24 hours she was back in dockyard hands, ‘having been blown practically in two by enemy mines’.

4

A danger that did present itself during the First World War was that of aerial bombardment. While Zeppelins and Gothas did pass close by, none actually deposited their deadly cargo of explosives directly on to the yard. In contrast, the nearby naval barracks did suffer horrifically from one bomb, this jettisoned by a Gotha bomber, with the raid occurring on 3 September 1917. Dropping a 110-pound bomb, the enemy aeroplane scored a direct hit on the naval barracks, this resulting in the death of 136 naval ratings. That the bomber, in company with three other aircraft, had located Chatham so easily was a result of the town lights not having been switched off. Helping ensure such a considerable loss of life was that of the bomb having hit the drill hall, this used to provide additional sleeping quarters. Having, as it did, a glass roof, the thousands of flying shards merely added to the number of victims. On another occasion, and as recorded by R.C. Lockyer, German aircraft were seen over Gillingham, with a number of anti-aircraft guns opening fire on them. In the dockyard, where Lockyer was then working on board

Erebus

, a large flat-bottomed monitor undergoing modification, he received a sudden fright when the guns of this vessel, despite her being in dry dock, were fired in the direction of the raiders. In his own words, Lockyer described what happened next:

At its very first shell my forge fell over and hot coals scattered over the deck. A Master-at-Arms bawled out, ‘Put that light out’ and a frantic scramble then took place for buckets of water to douse it.

5

While it was accepted that the bomber, through its growing speed and efficiency, was a threat in any future war, little thought during the inter-war period was given to ensuring the safety of the dockyard at Chatham. It was certainly accepted, and this beyond a shadow of doubt, that the yard would be a target, with its possible destruction a likely outcome. But instead of looking at the dispersal of its machinery and skilled workforce to potentially less vulnerable parts of the country, the entire facility was left ‘in situ’. Nor was the opportunity taken to camouflage or conceal some of its more prominent structures. Only from 1938 onwards, with war absolutely inevitable, was a decision taken to cover some of the older and highly inflammable wooden buildings with an external layer of asbestos boarding, this to minimise the effect of incendiary bombs.