Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (33 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

P

RINTING

L

UTHER IN

A

UGSBURG

Although this claims to be a Wittenberg publication, this work was in fact printed in Augsburg using a copy of Cranach’s woodcut. Shameless, but a tribute to the potency of “Brand Luther.”

These vernacular works played a crucial role in building support for the Reformation. They might serve as a surrogate preacher when an evangelical minister had been dismissed. They helped maintain the solidarity of the movement’s supporters in difficult times and won new

adherents to the cause. But the pamphlets were important in more ways than just for their content. Merely the fact that they could still be published and circulated when evangelical preaching was banned was a tangible symbol of defiance. As we have seen, Reformation

Flugschriften

were often instantly recognizable, with their strong visual appeal. The reluctance or inability of the city authorities to inhibit their sale was in itself an important victory for the evangelical cause. The city of Nuremberg, for instance, cautioned its printers against publishing Luther, but took no action against booksellers who continued to stock Reformation pamphlets. Here, and elsewhere, the sheer abundance of these pamphlets gave an irresistible impression of strength.

In the years between 1521 and 1525, when the pamphlet war was at its height, Luther and his supporters outpublished their opponents by a margin of nine to one. The impact of this was not lost on those in the city council chambers who had until this point held the line against the Reformation, if necessary expelling evangelical preachers from their cities. In this age, communities functioned largely by consensus. The city might be ruled by a relatively narrow oligarchy, but these councillors walked the same streets as their fellow citizens, they heard the catcalls and muttering in the market square, the tavern gossip. Townspeople might not have the vote, but they had many ways of making their views known. The overwhelming plurality of published literature on the evangelical side provided a sort of surrogate for a popular vote. It gave the clear impression of an emerging consensus, a new public mood for reform, particularly when it was backed, as it often was, by noisy demonstrations of disapprobation at attempts to preach conservative doctrine or circulate anti-Lutheran tracts. With the passage of time the city oligarchs found this increasingly hard to resist.

Much of this had been clear to the papal legate Aleander when he arrived in Worms to prepare for the Imperial Diet. He immediately sensed that these were unusual times. His arrival had been greeted by a flurry of hostile and scabrous pamphlets; the fact that this went unpunished emboldened the citizens to new indignities. Aleander was denied

access to his lodgings; men touched their swords significantly as he passed on the streets. Pictures of Luther were treated like holy relics. Men gathered in the square to debate Luther’s teaching, and nobles carried his books into meetings of the Diet. Here was the Reformation in a single, well-observed vignette.

24

Worst of all:

A shower of Lutheran writings in German and Latin comes out daily. There is even a press maintained here, where hitherto this art has been unknown. Nothing else is bought here except Luther’s books even in the imperial court, for the people stick together remarkably and have lots of money.

25

With respect to the press, this was only half right. There was a press newly established in Worms, largely because the emperor required one to print the official proceedings of the Diet, but it played little role in the publication of evangelical works.

26

These were all brought to Worms from elsewhere. This, of course, made retribution against the publishers well-nigh impossible, and the city authorities clearly did not feel secure enough to go after the local booksellers.

This was a trial of strength, as everyone knew, and pamphlets were major weapons of this struggle to determine the future direction of Germany’s religion. Often this was quite literally the case, as books, and their public circulation, became flashpoints in the battle for local supremacy. In Magdeburg an early polemical writing of Jerome Emser was pinned up in what Luther described decorously as “a shameful place,” probably the town’s privy or place of public execution. A rod was also attached to hint at the chastisement that would befall the author if he ever showed his face.

27

Official writings condemning Luther were torn down and evangelical writings pinned up in their place. In Erfurt in 1520 an anonymous pamphlet was affixed to the doors of the university’s Great College defending Luther and attacking Eck. The pamphlet sought to rally the university community in defense of Luther, but the language was far from academic.

We exhort in the Lord Jesus Christ, rise up and act courageously in the word of Christ. Resist by warding off the brutes; protest even with hands and feet against the most rabid detractors of that aforesaid Martin. Lest the ideas manifestly raised up by him from the dust into the light be somehow suppressed, fight back!

28

This was not exactly the spirit of Erasmus, and the fact that official academic space had been appropriated in this way was a serious offense. An official investigation was set in train but no culprits could be identified. Even the printer could not be brought to book, since the work had been commissioned from a printer outside the city, and bore no identifying marks (it was, in fact, the work of Melchior Ramminger of Augsburg).

29

This demonstration was clearly carefully planned, and represented a deliberate escalation of the confrontation with authority. Even in these academic circles there was a clear sense that the old ways of doing business, the language and formal procedures of disputation, no longer met the needs of the present situation. This sentiment had been building since the Leipzig Disputation of 1519. Johann Lang was responsible for publishing the proceedings of the disputation in Erfurt, but realized that the academic to and fro was not really comprehensible to anyone but a clerical insider. The printer, Matthes Maler, warned the unwary reader that he might find it a “chaotic sea of words.”

30

Many thought the Leipzig Disputation did not live up to the importance of the issues at stake, but it may have been simply that the medieval type of oral disputation, formal and extraordinarily long, did not lend itself to the medium of the printed pamphlet.

31

By 1521 the dam had burst; Germany’s cities had to choose between enforcing the Worms Edict or proceeding down the path of reform. The deluge of printed works, addressing the reform agenda in all its aspects, showed how the habit of obedience had now been overtaken by a clear desire to continue along the road indicated by Luther’s defiance. Surveying this great mass of literature, several things become clear. We can see the overwhelming, commanding presence of Luther as spiritual leader

of the movement. Luther’s works outstrip those of any other author by a factor of ten; he outpublished the most successful of his Catholic opponents by a factor of thirty. Even this bald statistic understates the dominant role of Wittenberg in the printed works of the Reformation. After Luther, three of the next four most published authors were Melanchthon, Bugenhagen, and Justus Jonas; the only author to break into this Wittenberg cartel was Urbanus Rhegius of Augsburg.

32

Melanchthon played a particularly important role as a Latin author. Even if we cast our eye over the less celebrated authors of the Reformation, the continuing role of Wittenberg as a guiding force is clear. The debate that followed the publication in 1523 of Luther’s

Judgment on Monastic Vows

drew forth supportive contributions from a number of authors on the evangelical side: Johann Schwan, Francis Lambert, Johann Briesmann, and Johann Eberlin von Günzburg. In 1523 all four were resident in Wittenberg.

33

The clear sense of direction provided by Wittenberg to the printing campaign of the early evangelical movement helps explain the relative doctrinal coherence of the Reformation in these early years.

34

There was one very important exception to this Wittenberg domination, for these years also witnessed the first significant interventions in the debate by local leaders. In addition to numerous reprints of the works of Luther and his Wittenberg colleagues, the Strasbourg presses published works by Zell, Bucer, and Capito; Augsburg had a prominent spokesman in Urbanus Rhegius; and Ulrich Zwingli emerged as a dominant force in Zurich. These men could speak with authority to their own congregations; as Zell put it in his

Christian Apology

of 1523, he was now putting into writing what he had already taught orally to over three thousand people. The preachers would bear witness, as they had in their sermons, that Luther’s teachings were not just the doctrine of denunciation, but the template for a new Christian art of living in their own communities. They insisted that Luther was pious and right, that his writings were “just and Christian,” that he was an “innocent revealer of truth.”

35

This sort of character reference was every bit as important as the trenchant controversy in which the Wittenbergers perforce engaged.

The local pastors also echoed Luther’s denunciations of the papacy and his criticism of the venality of the clergy. This to some extent vitiated the charge of rebellion and disobedience, one of the most telling weapons in the armory of Luther’s opponents. Such issues also spoke more directly to the concerns of their congregations than the more abstruse theological propositions developed by Luther in response to his Catholic critics. This was important, because it was precisely in these years that members of the lay community were themselves taking to print to express their own support for Luther’s teachings.

36

Here, too, the concentration was rather more on attesting to Luther’s credentials as a teacher and pastor than in articulating a particularly sophisticated view of his main theological precepts. They all recognized that Luther was a learned doctor whose dedication to the Christian faith had put him at odds with the institutional church. They accepted Luther’s precept that this truth could be established only on the basis of Scripture. Beyond this they were prepared to put a great deal of faith in Luther’s credentials as a man of God and truthful interpreter. As Lazarus Spengler, secretary of the Nuremberg City Council, put it in an influential tract, “No teaching or preaching has seemed more straightforwardly reasonable, and I also cannot conceive of anything that would more closely match my understanding of Christian order as Luther’s and his followers’ teaching and instruction.” Spengler then went on to make a highly significant remark. “Up to this point I have also often heard from many excellent highly learned people of the spiritual and worldly estates that they were thankful to God that they lived to see the day when they could hear Doctor Luther and his teaching.”

37

This was the wisdom of crowds: a growing consensus that in the battle with his shrill, intemperate opponents, Luther was the better man.

OPPOSING LUTHER

If Luther and his allies enjoyed an overwhelming supremacy in the field of print, this was not for any lack of effort on the part of defenders

of the traditional order. They recognized the danger, and the need that the Lutheran threat should be combatted. Luther had many and capable foes, and we have met several of them in preceding chapters: Tetzel, Eck, Cochlaeus, Emser. All these men showed courage, resolution, and persistence. But there is no doubt that, in publishing terms at least, they were swimming against the tide.

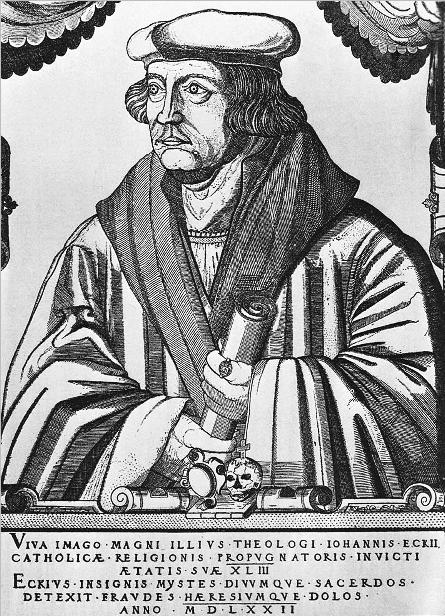

J

OHANN

E

CK

One of the small group of Catholic theologians who pursued Luther doggedly in print, despite the decided lack of enthusiasm for their works in the printing fraternity.

Why was the Catholic counterattack ultimately so ineffective? Several reasons have been advanced for the failure to dent Luther’s overwhelming supremacy in the battle of the books. It has, for instance,

often been suggested that in engaging Luther the Catholic theologians fought with one hand tied behind their back, inhibited by their reluctance to engage in controversy in the vernacular.

38

Part of the scandal of Luther was that he had appealed over the heads of his clerical brethren to a wider popular audience. Many of his opponents deplored that a theological quarrel should, in this way, be brought into the glare of public controversy; such a discussion should be conducted in Latin, the language of academic debate.