Blood Brotherhoods (18 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Clearly the policy of co-managing crime with the mafia was still fully operative. One of the most egregious cases of this policy concerned Sangiorgi’s immediate predecessor in charge of the Castel Molo police station, Inspector Matteo Ferro. Ferro had a close friendship with the

mafioso

who was to occupy a central role in Sangiorgi’s story: Giovanni Cusimano, known as

il nero

(‘Darky’) because of his complexion.

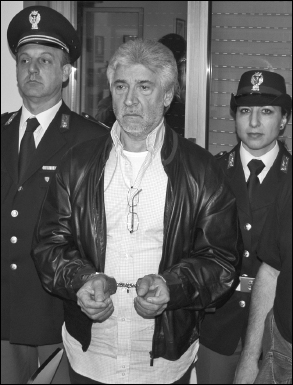

Salvatore Lo Piccolo, arrested in November 2007, in possession of a mafia rulebook (see p. 80). Lo Piccolo’s territory included the Piana dei Colli, where many of the earliest dramas of the Sicilian mafia’s history took place.

Inspector Ferro had already done a great deal to obstruct investigations into the Uditore mafia before Sangiorgi arrived; he had also gone on record to defend Darky, denying that he was a

capomafia

, calling him instead ‘an upright man, an individual who is completely devoted to law and order’. This despite the fact that Darky, among his many other crimes, had recently terrorised one landowner into granting him a lease on a villa worth 200,000 lire for the derisory annual fee of one hundred litres of olive oil. (A rent which, needless to say, Darky did not even deign to pay.) Once installed in the villa, Darky regularly received visits not only from the friendly local police inspector, Matteo Ferro, but also from a sergeant in the

Carabinieri

, and the editor of the local newspaper,

L’Amico del Popolo

(

The People’s Friend

). Everyone with any influence in the Piana dei Colli was a friend of Darky’s.

Soon after establishing himself in Castel Molo police station, Sangiorgi acted.

I quickly grasped that I needed to adopt a method diametrically opposed to the one that the police had used thus far. So at once I started openly fighting the mafia.

An open fight against the mafia. The simplicity of these words should not mislead as to just how difficult the task really was. When Sangiorgi revoked

the mafia bosses’ gun licences and handed out police cautions to them all, he had to overcome opposition on a scale that the police fighting the camorra in Naples had never encountered: Sangiorgi referred to ‘the intervention of Senators, MPs, senior magistrates and other notables’ in defence of the crime bosses. In other words, the mafia was already part of a network that reached up towards the higher echelons of Italy’s governing institutions. Sangiorgi’s story is a parable of just how difficult an open fight against that network can be.

At first, Sangiorgi achieved excellent results. ‘The mafia went into its shell’, he later recalled, ‘there was a positive reawakening of public morale, and a marked reduction in the number of crimes.’

Then in November 1875, eight months after Sangiorgi arrived in Palermo, a crippled old man, leaning heavily on a lawyer’s arm, was shown into his office. His name was Calogero Gambino, and he was the owner of a lemon grove in the Piana dei Colli, near the

borgata

of San Lorenzo. He began by saying that he had heard of Sangiorgi’s reputation as an honest and energetic cop, and so was now turning to him to obtain justice against the mafia.

Gambino had two sons, Antonino and Salvatore. Some eighteen months earlier, on 18 June 1874, Antonino had been ambushed and killed—shot in the back from behind the wall of a lemon grove as he was on his way to spray the family’s vines with sulphur. Gambino’s other son Salvatore was about to stand trial for his brother’s murder. But this ‘fratricide’ was nothing of the sort, old man Gambino explained. The mafia, in the shape of Darky Cusimano, had killed one son and framed the other: this was its last, cunning act of vengeance against his family.

Without needing to be told, Sangiorgi understood why Gambino had come to see him now: Giovanni ‘Darky’ Cusimano was dead, a recent victim of the semi-permanent mafia war to control the lemon groves. The bloody end to Cusimano’s reign in the Piana dei Colli left Calogero Gambino free to tell his extraordinary story.

A story that was a stick of political dynamite with a fizzing fuse. For old man Gambino also claimed that the police had helped the mafia arrange the fake fratricide. The national scandal surrounding former Chief of Police Albanese had reached its peak only a few months earlier. If what Gambino said was true, it would prove that the corruption had not ended with Albanese; it would prove that the mafia’s infiltration of the police in Palermo was still well-nigh systematic.

The ‘fratricide’ plot against Gambino’s surviving son was only the climactic moment of a campaign of vengeance that stretched back over fourteen years, to the time when Garibaldi’s expedition to Sicily made the island part of a unified Italian kingdom. The old man said that the mafia had originally targeted him because he was a well-to-do outsider who was not born in San Lorenzo. His son-in-law, Giuseppe Biundi, was the original source of his troubles; Biundi was the nephew of Darky’s underboss. In 1860 Biundi kidnapped and raped Gambino’s daughter to force a marriage. A few months after the wedding, Gambino’s new son-in-law stole several thousand lire from his house. The young man’s family connections made old man Gambino too afraid to report the burglary to the authorities, he said.

Then, in 1863, Giuseppe Biundi kidnapped and murdered Gambino’s own brother. The old man could no longer keep quiet: following his tip-off to the police, Biundi and his accomplice were caught and sentenced to fifteen years’ hard labour.

Sitting in Sangiorgi’s office eleven years later, Gambino explained the dread consequences of his actions.

First the mafia persecuted me for vile reasons of economic speculation. But after what I revealed to the police, there came another, much more serious reason for turning the screw on me: personal vendetta.

But vendetta did not arrive immediately: Giovanni ‘Darky’ Cusimano had to wait three years, until the revolt of September 1866.

At the outbreak of the revolt, Gambino was confidentially warned that he was in grave danger, and had to leave San Lorenzo immediately. His sons threw the family’s cash, clothes, linen, cooking implements and chickens onto a mule cart, and set off to take refuge at another farm managed by a friend of theirs. On the way, they were attacked by a party of seventeen

mafiosi

. A fierce gun battle followed; Salvatore Gambino was wounded in the left thigh. But both brothers knew the area well, and managed to escape over the wall of a nearby estate, abandoning the family’s possessions to be ransacked by their tormentors.

The Palermo countryside was by then almost completely in the hands of the rebellious squads. Fearing that their chosen place of safety no longer offered sufficient protection, the Gambino family went to Resuttana, the village next to San Lorenzo in the Piana dei Colli. There they were taken in by one Salvatore Licata. It was in Salvatore Licata’s house, the following day, that the Gambinos took delivery of a package from Giovanni ‘Darky’ Cusimano: it contained a hunk of meat from their own mare. As a mafia message, the horse flesh may not have had the cinematic flair of the

decapitated stallion deployed in

The Godfather

, but its meaning was very similar all the same: Darky had not yet concluded his business with the Gambino family.

Inspector Sangiorgi does not tell us what his thoughts were as he listened to old man Gambino—he was far too savvy a policeman to write those thoughts down. Yet to appreciate the full drama of what Sangiorgi was hearing, and the intrigue that he was being drawn into, we have no choice but to figure out how his mind began to work when he learned who had offered sanctuary to the beleaguered Gambinos in Resuttana in September 1866. Sangiorgi was an outsider to Sicily, a northerner. But he had been in Palermo long enough to know the baleful power of the Licatas. The very mention of the Licata name told him, more clearly than any other detail, that Gambino was hiding a crucial part of the truth.

Salvatore Licata, aged sixty-one at the time he took in the Gambinos, was one of the most venerable and best-connected

mafiosi

in the Conca d’Oro.

Like many important mafia bosses, including Turi Miceli from Monreale, Darky Cusimano from San Lorenzo, and don Antonino Giammona from Uditore, Licata had led a revolutionary squad into Palermo in 1848 and 1860. But during the 1866 revolt Licata mobilised his heavies to oppose the insurgents. They formed a countersquad. Licata, in other words, was one of the smart

mafiosi

who realised that he had more to lose than to gain by rebelling.

His son Andrea was an officer in the Horse Militia, a notoriously corrupt mounted police force. His three other sons were armed robbers and extortionists who were guaranteed impunity by the family’s connections.

Like the Licatas, and like don Antonino Giammona who was a pillar of the National Guard, many Palermo bosses broke their remaining links with revolutionary politics during the revolt of 1866.

Old man Gambino’s friendship with the fearsome Licata clan raises the very strong suspicion that Gambino and his sons were also

mafiosi

. Several aspects of his story stretched credulity too far. He was asking Inspector Sangiorgi to believe that he was entirely an innocent victim. Fear alone, according to Gambino, had kept him from going to the law when persecuted by Darky, even though that persecution had been going on for nearly a decade and a half. The way he described his murdered son Antonino was also suspicious.

My son Antonino was a young man who was full of courage. He had too much respect for himself to lose his composure and allow his enemies, and his family’s enemies, to assume too much familiarity with him. That is why Darky and his allies were constantly worried, afraid that my son had in mind to take out his revenge against them.

A man of bravado and self-respect who would not stand for being bullied. A ‘benign maffioso’, to use Marquis Rudinì’s term. This is how the mafia likes to represent itself to the outside world.

The conclusion forming in Sangiorgi’s mind was inexorable: old man Gambino and his two sons were not being persecuted

by

the mafia, they were participants in a struggle for power

within

the mafia. It was only when they faced final defeat in that struggle that old man Gambino got his lawyer to take him to the police. Sangiorgi was to be his instrument of revenge against his former comrades; turning to the state was a vendetta of last resort.

Fear must have honed Sangiorgi’s concentration as he listened to the rest of the story.

Once again, after sending the hunk of horseflesh to old man Gambino, Darky Cusimano was forced to postpone his campaign against the Gambino family. When the revolt of September 1866 was subdued there was a brutal crackdown by the authorities. Fearing that they had exposed themselves with their open assault on the Gambinos, Cusimano’s people made peace overtures. Emissaries approached Gambino, who was still living with countersquad leader Salvatore Licata, to propose what Darky termed a ‘spiritual kinship’: two of his lieutenants were to become godfathers to Gambino’s grandchildren.

Reluctantly—according to his own very selective narrative of events—old man Gambino agreed to the proposal, and decided not to report the attack he had suffered to the authorities. Much more likely, the ‘spiritual kinship’ was in reality an alliance between mafia bloodlines.

In Sicily, and in much of the southern Italian mainland, a godfather is called a

compare

, literally a ‘co-father’.

Comparatico

(‘co-fatherhood’) was a way of cementing a family’s important friendships, of extending the blood bond further out into society. Often a poor peasant would ask a wealthy and powerful man to become ‘co-father’ to his child as a sign of deference and loyalty. But ever since the days of old man Gambino and ‘Darky’ Cusimano,

mafiosi

too have taken advantage of

comparatico

: senior bosses establish ‘spiritual kinships’ as a way of building their following within the sect.

The Gambino family’s enforced stay with Salvatore Licata during the 1866 revolt produced another intriguing development: old man Gambino’s son Salvatore married one of Licata’s daughters.