Blood Brotherhoods (14 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Italy was governed between 1860 and 1876 by a loose coalition known as the Right. The Right’s leaders were typically landowning, conservative free-marketeers; they favoured rigour in finance and in the application of the law; they admired Britain and believed that the vote was not a right for all but a responsibility that came in a package with property ownership. (Accordingly, until 1882, only around 2 per cent of the Italian population was entitled to vote.)

The men of the Right were also predominantly from the north. The problem they faced in the south throughout their time in power was that there were all too few southerners like Silvio Spaventa. Too few men, in other words, who shared the Right’s underlying values.

The Right’s fight against the Neapolitan camorra did not end with Spaventa’s undignified exit from the city in the summer of 1861. There were more big roundups of

camorristi

in 1862. Late in the same year Spaventa himself became deputy to the Interior Minister in Turin, and began once more to gather information on the Honoured Society. While the publication of Marc Monnier’s

The Camorra

kept the issue in the public mind, Spaventa made sure that the camorra was included within the terms of reference of a new Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry into the so-called ‘Great Brigandage’, a wave of peasant unrest and banditry that had engulfed much of the southern Italian countryside. The outcome of the Commission’s work was a notoriously draconian law passed in August 1863—a law that heralds the most enduring historical irony of Silvio Spaventa’s personal crusade against organised crime, and of the Right’s time in power. The name for that irony is ‘enforced residence’.

The new law of August 1863 gave small panels of government functionaries and magistrates the power to punish certain categories of suspects without a trial. The punishment they could hand down was enforced residence—meaning internal exile to a penal colony on some rocky island off the Italian coast. Thanks to Spaventa,

camorristi

were included in the list of people who could be arbitrarily deprived of their liberty in this way.

Enforced residence was designed to deal with

camorristi

because they were difficult to prosecute by normal means, not least because they were so good at intimidating witnesses and could call on protectors among the elite of Neapolitan society. But once on their penal islands,

camorristi

had every opportunity to go about their usual business and also to turn younger inmates into hardened delinquents. In 1876 an army doctor spent three months working in a typical penal colony in the Adriatic Sea.

Among the enforced residents there are men who demand respect and unlimited veneration from the rest. Every day they buy, sell and meddle without provoking hatred or rivalry. Their word is usually law, and their every gesture a command. They are called

camorristi

. They have their statutes, their rites, their bosses. They win promotion according to the wickedness of their deeds. Each of them has a primary duty to keep silent about any crime, and to respond to orders from above with blind obedience.

Enforced residence became the police’s main weapon against suspected gangsters. But far from being a solution to Italy’s organised crime emergency as Silvio Spaventa hoped, it would turn out to be a way of perpetuating it.

In 1865, before these ironies had time to unfold, rumours of another criminal sect began to reach the Right’s administrators—‘the so-called Maffia’ of Sicily. The mafia would soon penetrate Italy’s new governing institutions far more thoroughly than did the camorra in Naples. So thoroughly as to make it impossible to tell where the sect ended and the state began.

R

EBELS IN CORDUROY

L

IKE THE CAMORRA

,

THE

S

ICILIAN MAFIA PRECIPITATED OUT FROM THE DIRTY POLITICS

of Italian unification.

Before Garibaldi conquered Sicily in 1860 and handed it over to the new Kingdom of Italy, the island was ruled from Naples as part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. In Sicily, as in Naples, the prisons of the early nineteenth century were filthy, overcrowded, badly managed, and run from within by

camorristi

. Educated revolutionaries joined secret Masonic sects like the Charcoal Burners. When the sect members were jailed they built relationships with the prison gangsters and recruited them as insurrectionary muscle. Soon those gangsters learned the benefits of organising along Masonic lines and, sure enough, the Bourbon authorities found it hard to govern without coming to terms with the thugs. In Sicily, just as in Naples, Italian patriots would overthrow the old regime only to find themselves repeating some of its nefarious dealings with organised crime.

But the Sicilian mafia was, from the outset, far more powerful than the Neapolitan camorra, far more profoundly enmeshed with political power, far more ferocious in its grip on the economy. Why? The short answer is that the mafia developed on an island that was not just lawless: it was a giant research institute for perfecting criminal business models.

The problems began before Italian unification, when Sicily belonged to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The authority of the Bourbon state was more fragile in Sicily than anywhere else. The island had an entirely justified reputation as a crucible of revolution. In addition to half a dozen minor revolts there were major insurrections in 1820, 1848, and of course

in May 1860, when Giuseppe Garibaldi’s redshirted invasion triggered the overthrow of Bourbon rule on the island. Sicily lurched between revolution and the restoration of order.

Under the Bourbons, Naples completely failed to impose order on the Sicilians, and the Sicilians proved too politically divided to impose order on themselves. Once upon a time, before the invention of policing, private militias beholden to great landowners kept the peace on much of the island. In the early nineteenth century, despite the attempt to introduce a centralised, modern police force, the situation began to degenerate. All too often, rather than being impartial enforcers of the law, the new policemen were merely one more competing source of power among many—racketeers in uniform. Alongside the cops were private armies, groups of bandits, armed bands of fathers and sons, local political factions, cattle rustlers: all of them murdered, stole, extorted and twisted the law in their own interests.

To make matters worse, Sicily was also going through the turmoil brought about by the transition from a feudal to a capitalist system of land ownership. No longer would property only be handed down from noble father to noble firstborn son. It could now be bought and sold on the open market. Wealth was becoming more mobile than it had ever been. In the west of Sicily there were fewer great landowners than in the east and the market for buying land, and particularly for renting and managing it, was more fluid. Here becoming a man of means was easier—as long as you were good with a gun and could buy good friends in the law and politics.

By the 1830s there were already signs of which criminal business model would eventually emerge victorious. In Naples the members of patriotic sects made a covenant with the street toughs of the camorra. But in lawless Sicily, scattered documentary records tell us that the revolutionary sects themselves sometimes turned to crime. One official report from 1830 tells of a Charcoal Burner sect that was muscling its way into local government contracts. In 1838 a Bourbon investigating magistrate sent a report from Trapani with news of what he called ‘Unions or brotherhoods, sects of a kind’: these Unions formed ‘little governments within the government’; they were an ongoing conspiracy against the efficient administration of state business. Were these Unions the mafia, or at least forerunners of the mafia? They may have been. But the documentary record is just too fragmentary and biased for us to be sure.

The condition of Sicily only seemed to worsen after it became part of Italy in 1860. The Right governments faced even graver problems imposing order here than they did in the rest of the south. A good proportion of Sicily’s political class favoured autonomy within the Kingdom of Italy. But the Right was highly reluctant to grant that autonomy. How could Sicily govern its own affairs, the Right reasoned, when the political landscape was filled with a parade of folk demons? A reactionary clergy who were nostalgic for the Bourbon kings; revolutionaries who wanted a republic and were prepared to ally themselves with outlaws in order to achieve it; local political cliques who stole, murdered and kidnapped their way to power. However, the Right’s only alternative to autonomy was military law. The Right ruled Sicily with both an iron fist and a wagging finger. In doing so, it made itself hated.

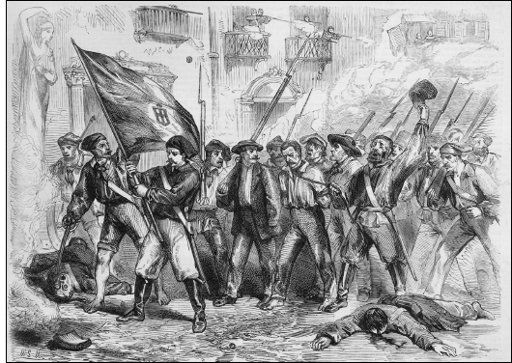

Palermo, 1860: freed prisoners parade their warder through the streets before shooting him. The Sicilian mafia was incubated in the political violence of the early to mid-1800s.

In 1865 came the first news of ‘the so-called Maffia or criminal association’. The Maffia was powerful, and powerfully enmeshed in Sicilian politics, or so one government envoy reported. Whatever this new word ‘Maffia’ or ‘mafia’ meant (and the uncertainty in the spelling was symptomatic of all manner of deeper mysteries), it provided a very good excuse for yet another crackdown: mass roundups of deserters, draft dodgers and suspected

maffiosi

duly followed.

Then, on Sunday 16 September 1866, the Right paid the price for the hatred it inspired in Sicily. On that morning, Italy—and history—got its first clear look at what is now the world’s most notorious criminal band.

Palermo in 1866. Almost the entire city was sliced into four quarters by two rectilinear streets, each lined with grimy-grand palaces and churches,

each perhaps fifteen minutes’ walk from one gated end to the other. At the city’s centre, the meeting point of its two axes, was the piazza known as the Quattro Canti. The via Maqueda pointed north-west from here, aiming towards the only gap in the surrounding ring of mountains. Palermo’s one true suburb, the Borgo, ran along the north shore from near the Maqueda gate. The Borgo connected the city to its port and to the looming, bastioned walls of the Ucciardone—the great prison.

Palermo’s other principal thoroughfare, the Cassaro, ran directly inland from near the bay, across the Quattro Canti, and left the city at its south-western entrance adjacent to the massive bulk of the Royal Palace. In the middle distance it climbed the flank of Monte Caputo to Monreale, a city famed for its cathedral’s golden, mosaic-encrusted vault, which is dominated by the figure of Christ ‘Pantocrator’—the ruler of the universe, in all his kindly omnipotence.

The magnificent view inside Monreale Cathedral was matched by the one outside: from this height the eye scanned the expanse of countryside that separated Palermo from the mountains. Framed by the blue of the bay, the glossy green of orange groves was dappled with the grey of the olives; one-storey cottages threw out their white angles among the foliage, and water towers pointed at the sky. This was the Conca d’Oro (‘golden hollow’ or ‘golden shell’).

More than any other aspect of Palermo’s beautiful setting, it was the Conca d’Oro that earned the city the nickname

la felice

—‘the happy’, or ‘the lucky’. Yet any outsider unwise enough to wander along the lanes of the Conca d’Oro would have soon detected that there was something seriously wrong behind the Edenic façade. At many points along the walls surrounding the orange groves a sculpted crucifix accompanied by a crude inscription proclaimed the point where someone had been murdered for reporting a crime to the authorities. The Conca d’Oro was the most lawless place in the lawless island of Sicily; it was the birthplace of the Sicilian mafia.

So no one was surprised that when trouble entered Palermo on the morning of 16 September 1866, it came from the Conca d’Oro. Specifically, it came down the long, straight, dusty road from Monreale, through the citrus gardens, and past the Royal Palace. The vanguard of the revolt was a squad from Monreale itself; it comprised some 300 men, most of them armed with hunting guns and wearing the corduroy and fustian that were habitual for farmers and agricultural labourers. Similar squads marched on Palermo from the satellite villages of the Conca d’Oro and from the small towns in the mountains behind. Some sported caps, scarves and flags in republican red, or carried banners with the image of the city’s patron, Saint Rosalia.