Blood Brotherhoods (89 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

There is no clearer illustration of this point than the Giulianos, a clan centred on Pio Vittorio Giuliano and a number of his eleven children, plus some of their male cousins. With its criminal roots in the smuggling boom that took place during the Allied military occupation, the family hailed from Naples’s notorious ‘kasbah’, Forcella.

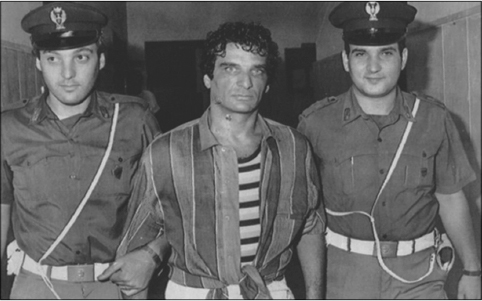

‘Ice Eyes’, early 1980s. Luigi Giuliano led his crime family from their base in the Forcella quarter of Naples—the historical home of the camorra in the city.

The Giulianos’ reign would persist into the 1980s and 1990s, when the clan eventually began to fall apart amid arrests, deaths and defections to the

state. The brashness of their power—the family occupied an apartment block that loomed like the prow of a huge ship at a fork in the road at the very centre of Forcella—would not have been unfamiliar to nineteenth-century

camorristi

with their gold rings, braided waistcoats and flared trousers. The second Giuliano boy, Luigi (born in 1949), took charge of the family business in his twenties. He was a wannabe actor and poet, a medallion man whose success with the ladies earned him the nickname ‘Lovigino’—an untranslatable coupling of the English word ‘Love’ and the affectionate form of Luigi. Lovigino’s menacing good looks and his startlingly blue irises explain his other moniker: ‘Ice Eyes’.

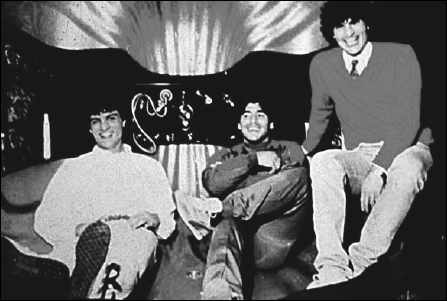

It is no coincidence that the Giulianos have left many eloquent photographs of their pomp. By far the most famous image from the Giuliano family album was confiscated during a police raid in February 1986. It shows two of the curly-haired Giuliano boys, Carmine ‘the Lion’ in a bright red V-neck, and Guglielmo ‘the Crooked One’ in white jeans. Both are beaming with delight as they recline in the most flamboyant bathtub in the history of plumbing: it takes the form of a giant conch-shell, its top half lifted back to reveal a gold-leaf interior, its surround in black stone, its base in pink marble with a pattern like stone-washed jeans. But the most remarkable thing about the photo is not the questionable taste of the Giulianos’ bathroom fixtures and fittings. Lounging between the brothers is a muscular little man wearing a grey and red tracksuit and an even bigger grin than them: Diego Armando Maradona, the greatest talent ever to lace up a pair of soccer boots.

The greatest soccer player of the age, Diego Armando Maradona, poses with members of the Giuliano camorra clan, who were keen to show off their taste in bathroom fittings (mid-1980s).

Argentinian superstar Maradona played for Napoli at his peak, between 1984 and 1992, and won the Serie A national championship twice. He became a demigod in the city, worshipped as no other sportsman anywhere has ever been: still now, his picture adorns half the bars in Naples. The notorious bathtub photo was not the only occasion during his time in the sky-blue shirt of Napoli when his name was associated with organised crime. In March 1989, he put in an appearance at the swish restaurant where Lovigino’s cousin was getting married: ‘Maradona at the boss’s wedding’ ran one headline. Four months later, he claimed that the camorra was threatening him and his family, and that he was too afraid to return to Naples for the start of the new season. There were unsubstantiated rumours of match-fixing. This was the summer when the conch-shell bathtub photo was made public. (Mysteriously, it was kept in a drawer in police headquarters for over three years.) It is also worth recalling that it was in Naples that Maradona’s well-documented problems with cocaine took a grip.

At the time, ‘the Hand of God’ denied knowing that the Giulianos were gangsters. His autobiography, published in 2000, is more forthcoming:

I admit it was a seductive world. It was something new for us Argentinians: the Mafia. It was fascinating to watch . . . They offered me visits to fan clubs, gave me watches, that was the link we had. But if I saw it wasn’t all above board I didn’t accept. Even so it was an incredible time: whenever I went to one of those clubs they gave me gold Rolexes, cars . . . I asked them: ‘But what do I have to do?’ They said:

Nothing, just have your picture taken

. ‘Thank you,’ I would say.

The point here is not whether Maradona’s links to organised crime were more substantial than he claims. His very visible friendship with the Giulianos was more than enough for their purposes. Many

camorristi

, particularly urban

camorristi

, have always sought good publicity; they have always sought to win the admiration of the section of the Neapolitan population that identifies with well-meaning miscreants. Whether by loud, expensive clothes and flagrant generosity, by shows of piety, by grand public funerals and weddings, or by rubbing shoulders with singers and sportsmen, generations of

camorristi

have won legitimacy in the eyes of the very people they exploit. Maradona’s own story, as the pocket genius risen from a shanty suburb of Buenos Aires, was a perfect fit with the camorra’s traditional claim that it was rooted in, and justified by, poverty. If the camorra from the slums of Naples had an official ideology, it would be the kind of pseudo-sociology that Lovigino ‘Ice Eyes’ Giuliano himself articulated:

In Forcella it isn’t possible to live without breaking the state’s laws. But we Forcella folk aren’t to blame. The blame goes to the people who prevent us doing a normal job. Because no one from a normal company is prepared to take on someone from Forcella, we are forced to find a way to get by.

Needless to say, ‘getting by’ involved extorting money from every money-making activity in Forcella; it involved illegal lotteries and ticket touting for Napoli games; it involved mass-producing fake branded clothes; it involved theft and drug dealing on a huge scale; and it involved appalling acts of violence. When Lovigino ‘Ice Eyes’ eventually turned state’s evidence in 2002, he confessed to the murder of an NCO killer called Giacomo Frattini. Frattini’s fresh-faced looks earned him the nickname of

Bambulella

—Doll Face—despite a body covered in jailhouse tattoos. The NF spent a long time planning what they would do to him. One idea was to crucify him in front of the Professor’s palace on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius. In the end, in January 1982, an execution party lured him into a trap, tortured him, and then summoned a friendly butcher to lop off his head and hands and cut out his heart. They left the pieces in separate plastic bags in a FIAT 500 Belvedere just off piazza Carlo III. A note from an imaginary left-wing terrorist group was left in a telephone box nearby: it called him the ‘prison executioner’, the slave of a ‘demented, diabetic fanatic’—meaning Raffaele ‘the Professor’ Cutolo.

Being flash like the Giulianos has never been the only style of criminal authority in Naples. Historically, the area to the city’s north is home to a quieter brand of

camorrista

who would also become part of the Nuova Famiglia.

Marano is a small agricultural centre that has long been notorious for camorra influence. In 1955, the son of the town’s former mayor, Gaetano Orlando, shot dead Big Pasquale, the ‘President of Potato Prices’. During the 1970s and 1980s, Gaetano Orlando’s nephews, Lorenzo, Gaetano, Angelo and Ciro Nuvoletta, became the most powerful criminals in Campania. They were initiated into Cosa Nostra during the tobacco-smuggling boom. Their farmhouse, which stood shrouded by trees on a hill just outside town, was the theatre of all the most important meetings during the war between the NCO and the NF.

The Nuvolettas preferred the subdued public image of their brethren in Cosa Nostra. Their wealth was vast, and as was the case with the many criminal fortunes built in the same part of Campania over the previous century,

it straddled the divide between lawful business and crime. The clan earned from construction as well as smuggling, property as well as extortion, farming as well as fraud. Sicilian heroin broker Gaspare ‘Mr Champagne’ Mutolo was initiated into Cosa Nostra on the Nuvolettas’ farm. He saw their riches at firsthand: they had warehouses of battery hens because they had a contract to feed all the military barracks in Naples. Thus, even during the new wealth of the 1970s,

camorristi

from the hinterland had not relinquished their traditional grip on the city’s food supplies.

This combination of lawful and illegal income explains the Nuvolettas’ preference for passing unobserved. For all their riches, their profile was so low that when, in December 1979, the

Carabinieri

captured Corleone

mafioso

Leoluca Bagarella in possession of a photograph of a businessman with salt-and-pepper hair, it took them months to put Lorenzo Nuvoletta’s name to the face. No wonder, then, that Lorenzo Nuvoletta was entrusted with being the

capomandamento

(‘precinct boss’) of the three Campanian Families of Cosa Nostra, the man whose job was to represent Neapolitan interests to the Palermo Commission, through his prime contact, Michele ‘the Pope’ Greco.

So the Nuova Famiglia reflected all the traditional diversity of organised crime in Naples and Campania. And that diversity also explains why it seemed that the atrocities might carry on without anyone ever achieving a military victory.

C

ATASTROPHE ECONOMY

G

IUSEPPE

T

ORNATORE

’

S

1986

FILM

I

L CAMORRISTA

IS A RAMBLING

,

RISE-AND-FALL

gangster melodrama based on the career of Raffaele ‘the Professor’ Cutolo. It plays back the embellished highlights of the Nuova Camorra Organizzata story to a soundtrack of plaintive trumpet and clarinet melodies that owe more than a little to

The Godfather

’s genre-defining score. Since

Il camorrista

first came out in 1986, endless reshowings through local TV, bootleg videos, and now YouTube, have irretrievably confused reality and myth in the popular memory of the Professor’s reign. The movie’s most resonant lines (‘Tell the Professor I did not betray him’ and ‘Malacarne is a cardboard

guappo

’) have become slogans—the Neapolitan equivalent of ‘I’ll make him an offer he can’t refuse’ and ‘Leave the gun, take the

cannoli

.’

Perhaps

Il camorrista

’s most visually arresting scene takes place in prison. The Professor is shown reading a history book in bed, in an immaculately pressed pair of sky-blue pyjamas. A low rumble in the background causes him to look up. The rumble becomes a shaking: first the ornaments on his bedside chest vibrate, then his metal bed frame starts clanking repeatedly against the wall, and his cell window shatters. Wails of panic rise in the background: ‘Earthquake!’ Staggering to his feet, Cutolo opens his cell door to watch Poggioreale prison plunge into anarchy. Clouds of dust rise from the floor of his wing, and chunks of plaster drop from the ceiling. The guards run hither and thither releasing screaming inmates from the cells. Within seconds, Cutolo has his arms around his two chief enforcers: ‘This is a chance sent to us by the Lord above! It’s gotta be the apocalypse for the old camorra!’