Blood Brotherhoods (22 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

B

ORN DELINQUENTS

: Science and the mob

I

N BOTH

N

APLES AND

P

ALERMO

,

THE LATE

1870

S INAUGURATED A QUIET PERIOD IN THE

history of organised crime. Successive Left governments seemed to find an accommodation with the camorra and mafia. The underlying problems that had made the new state such a welcoming host to the underworld sects became endemic: political instability and malpractice; police co-management of delinquency with gangsters; criminal rule within the prison system. But the issue of underworld sects did not disappear from public debate. Indeed

mafiosi

and

camorristi

loomed large in Italian culture during the 1880s and 1890s. Their deeds, their habits, and above all their faces were displayed for all to see—whether on the page or on stage. Italians were often fascinated and horrified by what they saw. But they deluded themselves that the spectacle was merely a primitive hangover, a monument to old evils that was about to crumble into the dust of history. Thus, while Italy could not eradicate the gangs, it could at least change the way it thought about them: the organised crime issue became a matter of perceptions. Unfortunately, illegal Italy showed itself to be even more adept at perception management than legal Italy. This was the new criminal normality. A normality that, with all its ironies, was set to welcome a third criminal brotherhood into its midst.

The Right had viewed criminal organisations, understandably enough, as something much more threatening than mere crime. The camorra and

the mafia (at least to those prepared to accept that the mafia was something more than an ‘ill-defined concept’) constituted a challenge to the state’s very right to rule its own territory; they were a kind of state within the state that no modern society could tolerate.

This view had always faced opposition, not least from lawyers who thought that the fight against the ‘anti-state’ did not give the government the right to trample over individual rights. One piece of legislation, passed in 1861, made lawyers particularly nervous: it targeted ‘associations of wrongdoers’. This was the law used in the anti-mafia trials of the late 1870s and early 1880s. It stipulated that any group of five or more people who came together to break the law were now deemed to be committing an extra crime—that of forming an ‘association of wrongdoers’. The government’s tendency to use this law as a catchall for clamping down on groups of political dissidents helped increase the lawyers’ anxiety.

The law was revised in 1889, and rephrased as a measure against ‘associating for delinquency’. But some fundamental legal dilemmas survived the rewrite. What exactly was an ‘association for delinquency’? How could it be proved, beyond reasonable doubt, that one existed? Rivers of legal ink were spilt in the search for a solution. The crime of ‘associating for delinquency’ only attracted quite minor penalties in any case—a couple of extra years in prison. So it was much easier to forget the elaborate business of dragging the mafia and camorra before a judge. Better to fall back on ‘enforced residence’, and send any conspicuous offenders off to a penal colony without a trial. Put another way, organised crime was to be pruned, and not uprooted.

The nitpicking legalistic approach to the mafia and camorra was a dead end. From the late 1870s until the end of the century, sociology seemed to have far greater purchase on the problem. And at that time, sociology largely meant

positivist

sociology—positivism being a school of thought that dreamed of applying science to society. From a properly scientific perspective, the positivists reasoned, lawbreakers were creatures of flesh and blood; they were human animals to be observed, prodded, weighed, measured, photographed, and catalogued. If only science could identify these ‘born delinquents’

physically

, then it could defend society against them—irrespective of what the legal quibblers said.

The most optimistic, and most notorious, attempt to identify a ‘delinquent man’ and a ‘delinquent woman’ by their physical appearance was articulated by the Turinese doctor Cesare Lombroso. He claimed to have identified certain anomalies in criminal bodies, like sticky-out ears or a bulky jaw. These ‘stigmata’, as he termed them, revealed that criminals actually belonged to an

earlier era of human development, somewhere between apes and Negroes on the evolutionary ladder. Lombroso made a great career out of his theory and defended it doggedly, even when some other sociologists demonstrated what claptrap it was.

Lombroso was not the only academic who thought science could unlock the crime issue. Others sought the key in factors like diet, overcrowding, the weather, and of course race. Southern Italians and Sicilians seemed to be made of different stuff from other Europeans, if not physically, then at least psychologically. In 1898 one celebrated young sociologist, Alfredo Niceforo, gave a derogatory twist to the mafia’s own propaganda when he argued that the Sicilian psyche and the mafia were one and the same thing.

In many respects the Sicilian is a true Arab: proud, often cruel, vigorous, inflexible. Hence the fact that the individual Sicilian does not allow others to give him orders. Hence also the fact that Saracen pride, conjoined with the feudal hankering after power, turned the Sicilian into a man who always has rebellion and the unbounded passion of his own ego in his bloodstream. The

mafioso

in a nutshell.

Neapolitans emerged in just as unflattering a light from Niceforo’s research: they were ‘frivolous, fickle and restless’—just like women, in fact. But the camorra was distinct from the Neapolitan ‘woman-people’ among whom it lived. After all, there was wide agreement that the camorra, unlike the mafia, was a secret society. The camorra’s weird rituals, its duels and the elaborate symbolic language with which

picciotti

addressed their

capo-camorrista

showed that the camorra was nothing less than a savage clan, identical to the tribes of central Africa as described by Livingstone or Stanley.

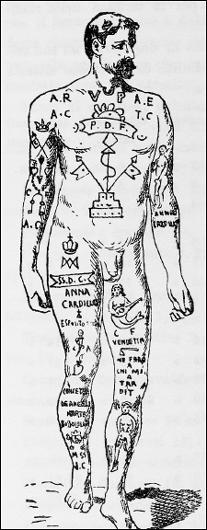

Camorra tattoos particularly fascinated ‘scientists’ like Lombroso and Niceforo. As far as anyone knew,

camorristi

had always adorned their skin with the names of the prostitutes they protected, the vendettas they had sworn to perform and the badges of their criminal rank. Tattoos served a double purpose: they were a sign of loyalty to the Honoured Society that also helped intimidate its victims. Like the flashy clothes early

camorristi

wore, tattoos tell us a great deal about the nature and limits of camorra power. At a time when the Society was rooted in places where the state scarcely bothered to extend its reach—in prison, or among the plebeian labyrinth of central Naples—it mattered little that these bodily pictographs could also be deciphered by the prison authorities and the police. However, needless to say, these subtleties escaped the criminologists, who just took tattoos to be one more bodily symptom of degeneracy.

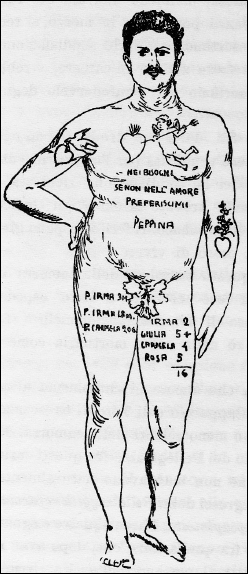

‘Camorra pimp’, with signature body adornments. Taken from one of many prurient studies of gangland tattooing published in the late nineteenth century.

‘Bloodthirsty camorrista’.

Positivist criminology became a fashion; in the name of scientific inquiry it pandered to the public’s fascination for secret societies and gruesome misdemeanours. A hungry readership was fed with titles like:

The Maffia in its Factors and Manifestations: A Study of Sicily’s Dangerous Classes

(1886);

The Camorra Duel

(1893);

Habits and Customs of Camorristi

(1897); and

Hereditary and Psychical Tattoos in Neapolitan Camorristi

(1898). Naples had a particularly avid market for guides to the structure and special vocabulary of the camorra. It was as if these were textbooks, part of an informal curriculum on the Honoured Society that the locals had to digest before they could lay claim to knowing Naples, to being truly Neapolitan.

Some of the authors of these guides were police officers and lawyers who brought a great deal of hard evidence to the debate about organised crime. For instance, it was shown that for reasons of secrecy, affiliates of the Honoured Society were actually grouped into two separate compartments: the junior

picciotti

belonged to the ‘Minor Society’ and the more senior

camorristi

formed the ‘Major Society’. Yet the same authors who relayed insights such as this also blithely threw in recycled folklore (about the camorra’s Spanish origins, for example), pseudo-scientific speculation, and plain old titillation. Many of the books carried garish illustrations of delinquent ears, prostitutes disfigured by horrendous scars, or torsos tattooed with arcane gang motifs. Underlying it all was the simplistic but seductive belief that seeing and knowing are the same thing. As one police officer-cum-sociologist wrote

The majority of

camorristi

have a dark complexion with pale tones, and abundant frizzy hair. Most have dark, sparkling, darting eyes, although a few have clear, frosty eyes. Their facial hair is sparse. Apart from a few harmonious physiognomies (which are in any case often spoiled by long scars), one can observe many noses that are misshapen, large or snubbed. There are also many low or bulbous foreheads, large cheekbones and jaws, ears that are either enormous or tiny, and finally rotten or crooked teeth.

Positivist criminology treated crime as if it were no more complicated than a smear on the bottom of a Petri dish. Yet

mafiosi

and

camorristi

, just like the rest of us, are capable of rational, strategic planning. And, more even than the rest of us, they have every reason to be fascinated by tales of secret societies and gruesome misdemeanours . . .

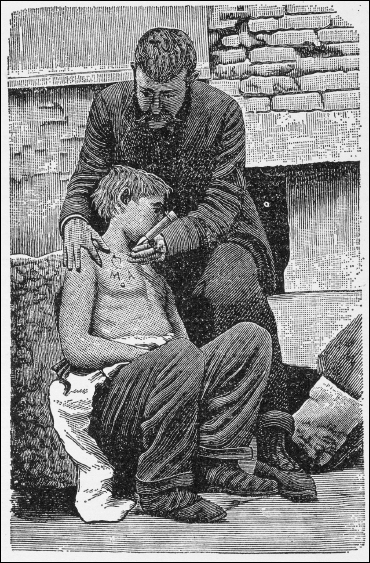

A youngster gets his first criminal insignia. A street tattooist at work in Naples.

A

N AUDIENCE OF HOODS

A

MONG THE MORE INTRIGUING ITEMS HELD IN THE

N

ATIONAL

L

IBRARY IN

N

APLES IS A

photograph, no less, of the moment when the camorra was founded. Or at least, that is what it appears to be. With remarkable clarity it shows the camorra’s founding members—all nine of them—arranged in a semi-circle in a large prison cell. They are evidently taking an oath by swearing on the sacred objects that lie on the floor before them: a crucifix with crossed daggers arranged at its foot. The new members have their gaze fixed on the man who seems to be leading the ceremony. He is a confident figure with a brimmed hat pushed to the back of his head, who is shown pointing at the dagger and crucifix and placing a reassuring hand on the shoulder of one nervous-looking novice.

The photograph was taken during rehearsals for

The Foundation of the Camorra

, a play first performed on the evening of 18 October 1899. It may well have been a publicity shot. If so, it certainly did the trick. Interest in the play was such that tickets for the second night sold out by midday and the

Carabinieri

had to be called in to calm the scrum of frustrated theatregoers.