Blood Brotherhoods (24 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Villari’s call to moralise Naples from top to bottom gained new resonance when the Left assumed power, with a brand of pork-barrel politics that gave

camorristi

even greater access to public spending. Villari inspired a generation of radical conservative campaigners to raise what became known as the ‘Southern Question’. One of those to follow Villari’s call was Pasquale Turiello, who in 1882 diagnosed what he termed the individualism, indiscipline and ‘slackness’ in Neapolitan society. Turiello argued that the Left’s shambolic sleaze both reflected and cultivated Neapolitan ‘slackness’. The city was being divided up between bourgeois political clienteles from above and proletarian camorra gangs from below.

The events of the 1880s and 1890s would confirm Turiello’s grim diagnosis and demonstrate his belief that it applied across much of southern Italy and Sicily, and even to the national political institutions. In 1882, the right to vote in general elections was finally extended to include about 7 per cent of the population. Any male who paid some tax or had a couple of years of primary school education could now go to the polls. Another reform followed in 1888: the electorate for town and provincial councils was broadened; and the mayors of larger towns were now to be elected. The spread of democracy swelled the market in political favours.

Mafiosi

and

camorristi

—either directly, or through their friends in national and local government—gained the power to share out such appetising perks as exemptions from military service, reduced local authority tax assessments, and town hall jobs. Other quasi-public bodies, like charities, banks and hospitals, helped grease the wheels of patronage.

Meanwhile, in Naples, the paradigm of the slack society, an appalling cholera epidemic struck in 1884. The entire bourgeoisie and aristocracy fled in panic. Some 7,000 people died, most of them from the alleys and tenements of the low city, which one contemporary said were like ‘bowels brimming with ordure’. In the epidemic’s aftermath the call went up to ‘disembowel’ the city. Tax incentives and public money were quickly allocated to support ambitious plans for slum clearance and sewer construction. For the next twenty-five years, the modernisation of Naples proceeded with agonising slowness and inefficiency. All the while, the city’s political cliques squabbled over the trough.

At every level of government, the slack society had enormous trouble creating and enforcing good reforms that benefitted everyone. Instead, it produced endless political fudges that fed temporary alliances of greedy politicians and their hangers-on. Indeed, when it came to dealing with the mafia and the camorra, the most important reforms were often the least likely to be implemented: policing is a prime example. On this point, as on others, there is no clearer way to illustrate the weaknesses of the slack society than through the life of an individual policeman.

In 1888 Ermanno Sangiorgi, the policeman who had first discovered the Sicilian mafia’s initiation ritual, was working in Rome as a special inspector at the Ministry of the Interior. By that time he had found happiness in his personal life, although that happiness once more brought down trouble from above. While he was still in Sicily, six years after his wife’s death, he began

an affair with a colleague’s wife. He was punished for what a senior civil servant called his ‘scandalous conduct’ by being transferred immediately, in December 1884. (The Ministry evidently regarded sexual morality as a more serious matter than consorting with gangsters.) Sangiorgi’s new love, a Neapolitan called Maria Vozza, twenty years his junior, followed him. She had to live in separate accommodation to avoid damaging his career any further. The two would remain together for the rest of his life.

In September 1888 Sangiorgi was sent back to Sicily on a secret mission to inspect the island’s unique mounted police corps, in preparation for a root and branch reform. He found that Palermo police headquarters was ‘in a complete state of confusion and disorder’; Trapani was worse. The mounted police corps did not even keep proper records of what crimes had been committed. Two of its most senior officers in Palermo had ‘intimate relationships with people from the mafia’. The result was not a surprise. As Sangiorgi wrote, ‘It would be dangerous to be deceived: the mafia and banditry have incontrovertibly raised their heads.’

No action was taken. Not for the last time, Sangiorgi’s hard work failed to produce any political effects.

The results for Sangiorgi’s career were positive, however. In 1888 he was picked to manage security when the King visited the turbulent region of Romagna. He did the job so well that in 1889, in Milan, he became Italy’s youngest chief of police. His rapid progress earned him the rare accolade of a newspaper profile.

Sangiorgi is only forty-eight. He is reddish-blonde, likeable, and knows how to conceal the cunning required by his job beneath a layer of affable bourgeois calm. He is as alert as a squirrel, an investigator endowed with a steady perspicacity.

The year after this profile was published he was transferred to Naples, a city where the police still enjoyed one of the worst reputations of any force in Italy, a city in ferment in the aftermath of the cholera epidemic of 1884 and the ‘disembowelling’ that followed it. As he had done in Sicily, Sangiorgi immediately set about breaking up the traditionally cosy relationship between the police and organised crime. On 21 February 1891, one of Sangiorgi’s officers, Saverio Russo by name, paid the ultimate price for this ‘open fight’ against the camorra when he was murdered by a

camorrista

he was trying to arrest. One well-informed newspaper commentator warned his readers against taking this shocking incident as an indication that gangsterism was out of control. Indeed, crime had decreased considerably in recent months:

Without any doubt a great deal of the credit for this must be given to the new Police Chief Sangiorgi. Of course it is no easy matter purifying the environment inside Police Headquarters and the local stations. Nor is it an easy job to shake up officers who are not always diligent and who previously went as far as to protect gangland. But the good results that Police Chief Sangiorgi has obtained so far, his sharp sagacity and great experience, constitute a guarantee for the government and citizenry alike.

Trouble cropped up in Sangiorgi’s personal life while he was in Naples. In February 1893 he was mortified to learn that his son from his first marriage, Achille, by now a coal merchant in Venice, had been arrested for cheque fraud; to Sangiorgi’s great shame, the story was reported in the press. The Ministry of the Interior looked into the case, but could only express sympathy for a hard-pressed father’s lot.

The supreme boss of the Honoured Society when Sangiorgi arrived in Naples was Ciccio Cappuccio, known as ‘Little Lord Frankie’. His specialism was a traditional area of camorra dominance: the market in horses, particularly the army surplus nags that were occasionally auctioned off to the general public. Rigging auctions was easy: the

camorristi

only had to bully other bidders. But the camorra’s control over the horse trade was also more insidious.

Marc Monnier’s father had been a keen equestrian and occasional horse dealer back in the 1840s and 1850s, so the Swiss hotelier had witnessed firsthand how

camorristi

used the uncertainties of the business to wheedle themselves into every possible economic transaction. Buying a horse from a stranger in Naples was always risky. No one could guarantee that, once the money had been handed over, the animal would not turn out to be frightened of the city’s clamour or too weak to cope with its hills. No one, that is, except a

camorrista

. For a share of the price,

camorristi

promised to make business deals run smoothly—on pain of a beating, or worse. The camorra also controlled the supply of horse fodder: many bosses, including Little Lord Frankie, doubled as dealers in bran and carobs. From this base they could exercise total control over the city’s ragged army of hackney-carriage drivers.

Little Lord Frankie passed away, of natural causes, in early December 1892. His death became the occasion for a disturbing display of just how deeply dyed by illegality was the slack fabric of Neapolitan society. From Police Headquarters, Sangiorgi could do little more than watch.

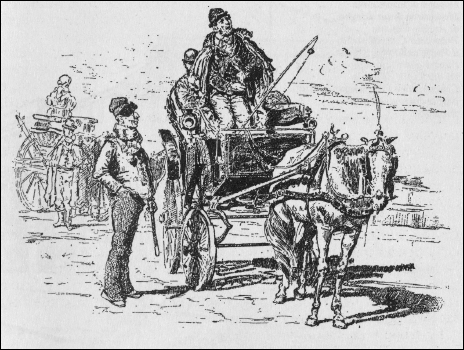

Day-to-day criminal business in Naples: a

camorrista

, in typical flared trousers, takes protection money from a cab driver (1880s).

Little Lord Frankie’s obituary in an important new Neapolitan daily,

Il Mattino

, was lavish in its praise. Here was a righter of wrongs, a proletarian justice of the peace. With a flush of pride,

Il Mattino

recalled the time when he had single-handedly downed twelve Calabrian

camorristi

in a knife fight in prison. But it was wrong to call him a ‘bloodthirsty, born delinquent’.

He was exceptionally nice: a model of decorum, respectful and deferential. He had a grim look in his grey eyes. But he strove constantly to moderate it by applying the sweetness and docility of a man who knows his own strength—a man who is absolutely sure that nothing in the world can resist his will.

Evidently it was not only the

lumpenproletariat

of the Vicaria quarter who embraced the myth of the noble, old-style

camorrista. Il Mattino

, like its notorious editor Edoardo Scarfoglio, was hysterically right wing and utterly corrupt—the mouthpiece of the worst elements in the Neapolitan political class. But what is both shocking and revealing about its coverage of Little Lord Frankie’s death is the way it tolerates, and even celebrates, the private statelets that camorra bosses were able to carve out in large areas of the city.

Little Lord Frankie’s last journey was a statelet funeral. Six horses drew an elaborate hearse, covered in wreaths, on a tour of half the city. The mourners

were led by every cab driver in Naples, and a procession of sixty hackney carriages. Then came a huge crowd of awestruck followers, all telling tales of the dead man’s ‘heroic and chivalrous deeds’, according to

Il Mattino

. The paper even published a poetic lament for Little Lord Frankie.

Who will defend us now?

Without him, what will we do?

Whoever can you run to

If a wrong is done to you?

Naples was still a city where the rule of law and honesty in public affairs seemed alien concepts.

A few months after Little Lord Frankie’s posthumous show of force, Sangiorgi found himself at the centre of a riot that, for one brief moment, laid bare the contorted entrails of the slack society. And despite his ‘steady perspicacity’, and ‘sharp sagacity’, the notorious hackney-cab-drivers’ strike of August 1893 would prove too tough an assignment for the determined Police Chief. For the first time in decades, the camorra took to the streets in force.

The events of the strike itself can be quickly related. The cab drivers’ anger was triggered by a proposal to extend the city’s tram system. So on 22 August three thousand cabbies launched a violent street protest to coincide with patriotic demonstrations against the murder of some Italian workmen in southern France. Socialists, anarchists and a hungry mob from the low city soon joined in. Sangiorgi was in bed with a severe fever when the disorder broke out. While he was away from work, a scrum of his officers on the hunt for rioters assaulted customers in the Gambrinus, the most prestigious café in the city. Sangiorgi crawled back to his desk the following morning to find that the police had become the targets of mass fury: there were pitched battles in the alleys between rioters and the forces of order. A boy of eight, Nunzio Dematteis, was shot in the forehead by a

Carabiniere

defending a tram from the mob. News quickly spread that the police were to blame for the boy’s death. The crowd carried his bleeding body aloft and marched on the Prefecture. Sangiorgi’s officers blocked their path and a grotesque tug of war over the corpse ensued. Some local parliamentarians demanded that the police withdraw their ‘provocative’ presence from the streets. The army was called in to restore calm.