Battle Story (9 page)

Authors: Chris Brown

Perhaps the single most telling strike by air power in the whole conflict was the destruction of the

Prince of Wales

and the

Repulse

(Force Z) as they steamed toward Kuantan with the intention of disrupting reported Japanese landings there. Force Z was struck on the morning of 10 December 1941 by a succession of ‘Nell’ torpedo bombers operating from airfields in French Indo-China. Sinking the two ships was not simply a blow to the power of the navy; it was a great blow to both civilian and military morale and rather set the tone for the rest of the campaign. Of all the navies in the world, the British should have been more aware of the power of aircraft at sea since just the year before a force of obsolete Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers had destroyed one Italian battleship and severely damaged another two in an attack on Taranto.

The Type 99 ‘Sally’, Type 99 ‘Lily’ and Mitsubishi G4M ‘Betty’ bombers, among others, were used extensively throughout the Malayan campaign. Due to poor surface-to-air communications,

the army air service provided little in the way of integrated air support for troops on the ground and much of its effort was focused on bombing towns and cities. The scarcity of anti-aircraft guns and limited quantities of ammunition, coupled with the sheer overwhelming numbers of Japanese aircraft, meant that there was little the Allies could do to prevent them from attacking. Although considerable damage was done to harbour facilities in Singapore, the chief purpose of the raids was to disrupt communications and demoralise the military and civilian population, a process which became more and more successful as it became apparent that the Allies could do nothing to prevent the attacks.

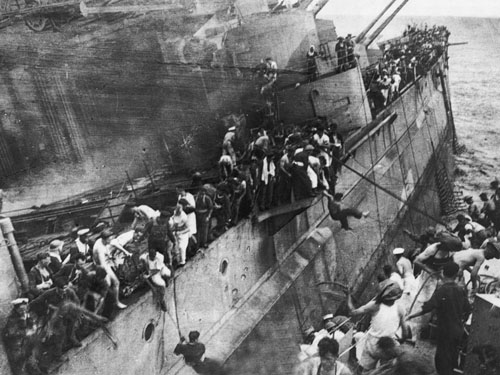

28. The rescue of Force Z survivors, 10 December 1941.

‘B

ETTY

’

With a top speed of about 250mph and a weapon payload of over ¾ ton, the ‘Betty’ – or Mitsubishi G4M – was comparable to other twin-engined bombers of her class, but was very vulnerable. To keep overall weight down – and consequently achieve a better speed – there was virtually no protection for the crew and the lack of self-sealing fuel tanks made the ‘Betty’ very vulnerable in combat. A number of ‘Bettys’ were used in the torpedo-bomber role against the

Prince of Wales

and the

Repulse

.

29. An Imperial Japanese Navy Mitsubishi G4M ‘Betty’ bomber.

BEFORE BATTLE

Percival’s general policy was unsuitable and unworkable in the circumstances of late 1941, and was not especially consistent. His initial troop commitments were not particularly rational and became increasingly irrelevant as the campaign developed. The prize – at least in the British view – was the great Singapore naval base, which could only be protected if there was adequate air power available, and the air power could only be maintained and adequately deployed if there were enough airfields to support the aircraft, but defending the airfields meant a heavy commitment of army resources. The necessary aircraft were not available, so protection of the fields was, essentially, redundant from the very beginning of the campaign. In addition to airfield protection, Percival also had to find the means of repelling an invasion wherever a force might land.

Percival did not develop a consistent policy for the campaign, but also failed to adjust his thinking to the situation, often endeavouring to make the circumstances fit the plan rather than the other way around. He alternated between plans to develop a strong defensive line, which would force the Japanese to concentrate their forces where his own troops would be able to take advantage of the superior British artillery, and a policy of slowing the Japanese advance while preparing for what he

called ‘the main battle’ further south. Neither policy was really valid since neither gave any real consideration to what the enemy intended to do or how he intended to achieve his aims. Some of the ‘wishful thinking’ among the British command generally – not just Percival – was the product of unrealistic assessments of both the Allied and Japanese capabilities – the belief that the Japanese advance could be stopped in its tracks by artillery being a case in point. The British and Commonwealth forces did have a considerable quantity of high-quality artillery, but had not developed the necessary integration within divisional structures to make it effective.

Equally, the policy of a gradual withdrawal while preparing for a ‘main battle’ would have been a challenge for a highly trained and well-articulated army with confidence in itself and its leaders. There was nothing intrinsically wrong with the troops of Malaya Command, but it was not a trained and cohesive force. Poor leadership, bad decisions and unworkable policies, combined with a complete absence of armour, inefficient communications and totally inadequate air cover made Malaya Command formations extremely vulnerable to the daring and well-coordinated manoeuvres of the Japanese Army.

Whether the campaign would be a matter of forcing the Japanese to attack a strong defensive line and bring about static warfare, or of forcing them to take heavy casualties en route to a concentrated battle in southern Malaya was really not a decision that Percival could make; General Yamashita would not allow him that luxury. His policy was based on what Japanese commanders called a ‘driving charge’. His troops were to force battle on the enemy at every opportunity and to pursue him relentlessly, specifically to prevent him regrouping either to build a defensive line or concentrate for a major battle.

In order to achieve and maintain the tempo necessary for such a policy, Yamashita’s army needed to focus their attack along the excellent road system. This was not lost on British commanders, who tried repeatedly to deny passage to enemy forces. These

attempts were sometimes relatively successful in the short term, but were never really effective. In part this was due to the Japanese superiority in armour. The Allied anti-tank weapons were not ineffective, but they lacked the mobility of tanks. When the Japanese encountered serious resistance they simply moved infantry off the road and searched for flanks of the defenders. Once they had located the limits of the Allied deployment, they ‘hooked’ back on to the road behind the defenders and encircled them, preventing communications and reinforcements, or at least forcing a withdrawal. This quickly led to a culture of retreat. At a tactical level, battalion and brigade commanders were reluctant to risk the destruction of their command in actions that were, ostensibly, peripheral to the ‘main battle’ planned for the near future; in fact, they were repeatedly advised not to risk heavy casualties. At a more personal level it bred a degree of reluctance among the troops. If the Japanese could not be stopped, why should a soldier risk his life if his unit was going to be withdrawn in the near future anyway?

Tomoyuki Yamashita

Born in 1885 in the Kochi prefecture, Shikoku, Tomoyuki Yamashita joined the army in 1905 and first saw active service against the Germans in Shantung, China, in 1914. He graduated from the Imperial Army War College in 1916 and was a military attaché at Berne from 1919–22. He was an advocate of a political movement known as the ‘Imperial way’, which put him at odds with several of his contemporaries and superiors. Yamashita served as Japan’s military attaché in Vienna, Austria, in 1928, but had retired to Japan to command an infantry regiment by the end of 1930. His view that Japan should extricate herself from the war in China and avoid war with Britain and the United States made him unpopular, and for some time he was relegated to a backwater post in the Kwantung Army.

He was appointed to the command of the Twenty-Fifth Army only a month before the invasion and became known as the ‘Tiger of Malaya’ on account of his remarkable success. He fell out of favour again in 1942 for referring to the people of Singapore as ‘citizens of the Empire of Japan’, which was contrary to the general policy that people in occupied territories should be subjects with duties and obligations, not citizens with rights. Yamashita spent the next two years in Manchuria, far from the main theatres of the war. Recalled to service in 1944, Yamashita fought with skill and tenacity. His attempt to prevent Manila from becoming a battlefield by withdrawing all Japanese forces without a fight was foiled by Admiral Iwabuchi, who seized the city with a large force of Imperial Navy infantry and military police units.

After a very questionable trial in which the prosecution accepted hearsay evidence and anonymous witnesses, Yamashita was sentenced to death and hanged. What are claimed to be the steps to the scaffold are preserved in the Penang War Museum.

30. Yamashita and Percival discussing surrender, 15 February 1942.

Within a matter of days, the pattern for the whole campaign had been set – the Japanese pushed forward as quickly as they could and the Allied commanders tried to maintain the integrity of their formations as they retreated. To some extent this was not unwise; if there was to be a ‘main battle’ in southern Malaya, the army had to be preserved as an effective force. The two problems being that the army as a whole was not an effective force in the first place and that the failure to impose much in the way of delay on the Japanese meant that the formations could not be properly rested, replenished and re-equipped to take a useful role as the campaign progressed.

Inadequate communications, incompetent staff work and a rapidly developing disposition toward retreat made the situation worse than it needed to be. On the occasions where Allied troops inflicted a local defeat on the Japanese they were often withdrawn because they were in danger of becoming isolated, but sometimes they were pulled out of action through sheer incompetence.

On a number of occasions, the Japanese were able to make an advance simply because there was nobody to delay them. On others, they were able to make breakthroughs that took them well into the Allied lines of communication and to destroy or capture great quantities of men and materiel, simply because there were no supporting Allied troops in place when a front-line unit was overrun or forced to abandon the road and take cover in the countryside. Naturally, news of such incidents travelled quickly among other units in the area and lost nothing in the telling, thus encouraging the belief that the Allied forces were incapable of standing up to the Japanese. Given the huge propaganda effort that had gone into convincing Allied troops in general – and British troops in particular – that the Japanese were racially inferior and that their equipment was poor, it is hardly surprising that Malaya Command as a whole was in something of a state of shock well before the end of January 1942. The morale of the troops had been badly undermined by constant retreating and the fact that the skies were dominated by the Japanese, as well as the loss of the only two major warships in the theatre.

Things were no better at the top of the command structure. Wavell was not really in tune with the battle at any point and was unable to instil a sense of purpose in Percival and also did not have the authority to force Shenton Thomas to make any kind of positive contribution to the war effort, which helped to undermine Percival’s authority and confidence. Percival’s policy was to inflict as much damage as possible during a slow retreat, but he was not prepared to make units fight to the last while others withdrew to more favourable positions. General Heath had always favoured a general withdrawal so that the Japanese could be engaged from a position of greater strength in northern Johore, rather than wearing the troops out with continual actions that seemed to do little or nothing to impede the Japanese advance. General Bennett was utterly dismissive of all soldiers except the Australians and cheerfully undermined all of his colleagues and most of his subordinates.