Battle Story (14 page)

Authors: Chris Brown

40. Gen. Wavell in Singapore inspecting coastal guns, November 1941.

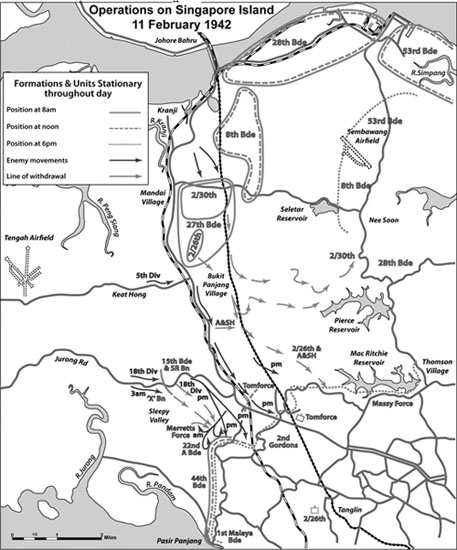

11 February | |

| 0000hrs | Japanese troops secure Bukit Timah junction. |

| 0300hrs | 18th Division advance toward Bukit Timah. |

| 0530hrs | 15th Brigade ordered to counter-attack and break contact with the enemy by going cross country toward 22nd Brigade. |

| 1300hrs | Bennett’s counter-attack to retake Bukit Timah abandoned. |

Around 0300hrs on 11 February elements of 18th Division, with a modest amount of armoured support, advanced from the Tengah area toward Bukit Timah along the Jurong Road.

Around 0530hrs Brigadier Coates, aware that 15th Brigade was in danger of being completely surrounded and overwhelmed, gave orders to cancel the counter-attack and to break contact with the enemy. This was easier said than done. Japanese advances meant that much of the Jurong Road was now impassable and Coates ordered his remaining units to strike out cross-country toward the positions of 22nd Brigade.

To the north, troops from 5th Division, with a strong armoured element, had advanced from their concentration area and despite a strong stand by 2/29th, were able to reach Bukit Panjang village and then turn south toward Bukit Timah. At about 2230hrs they encountered the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, who put up a fierce fight but could not hope to stop a column of fifty or so tanks.

By midnight Japanese troops had secured the Bukit Timah junction, cutting communications to 15th Brigade, but did not press on into Singapore city, though there was really precious little to stop them.

Operations of 11 February 1942.

By this time several units had simply been destroyed and others so badly damaged that they were increasingly being formed into ad hoc units. Breakdown of discipline was also becoming a problem, with considerable numbers of personnel – chiefly British and Australian – roaming around in search of loot or any means of escape.

Now that Bukit Timah was in Japanese hands, they were well positioned to advance westward through the central part of the island toward the Pierce and MacRitchie reservoirs. The defenders had already lost the bulk of their stores when the Bukit Timah supply dumps were overrun, now their very limited water supplies would be under threat as well. Early on the 11th, Bennett had ordered another counter-attack to retake Bukit Timah, but by 1300hrs this attempt had been abandoned as impractical since by this time a large proportion of both 5th and 18th Divisions – with a large number of tanks – had occupied the area. There was intensive fighting and heavy casualties on both sides, but the Japanese were not to be budged.

To the north, in the causeway area, the Japanese Guards Division made rather slower progress than 5th and 18th Divisions in the south and west, but had advanced along the line of the Sungei Mandai toward Mandai Ridge, threatening the southern flank of 8th Brigade and putting pressure on the left flank of 27th Brigade.

The battle was clearly going very badly for the Allies, but Yamashita was faced with serious problems of his own. Ostensibly his tanks had stopped at Bukit Timah because they had reached their objective, but Japanese units had repeatedly exceeded objectives during the peninsula campaign. Although Yamashita had paused for a week in Johore before making his attack, the efforts of the preceding weeks had exhausted his troops and his supplies. To some extent the rations situation could be eased by seizing food from shops and homes, but that was hardly a reliable approach to feeding his army. Other shortages, and especially of tank and small arms ammunition, could only be addressed by bringing materiel to the front (though there was no great stock anywhere in the peninsula) or by bringing the battle to a conclusion. Even so, it was clear from the Allied perspective that the battle could not continue very much longer. Yamashita saw the situation in the same terms and he now called on Percival to give up the fight. Percival forwarded the message to Wavell, saying that although he had no way of communicating with the

Japanese commander, he had no intention of surrendering at this juncture. All the same, he issued orders to destroy military installation and materiel to prevent it falling to the enemy. Under the circumstances, this was a perfectly sensible approach, but it further undermined morale among the troops and the civilian population. Denying materiel to the enemy was a clear indication that surrender would be offered in the very near future, so what was the value of continuing the fight at all?

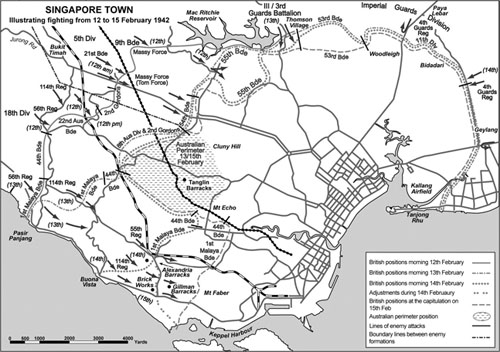

12 February | |

| 0800hrs | 8th Brigade come under attack by Japanese. |

13 February | |

| Perimeter formed by the Allies, but very congested area. | |

| Combat continues throughout the day. | |

| 1430hrs | Percival calls a conference at his headquarters to discuss battle prospects. |

14 February | |

| 0830hrs | 1st Malaya Brigade attacked. |

| 1600hrs | 1st Malaya Brigade forced back to the Brickworks. |

15 February | |

| 0930hrs | Percival calls a conference at his headquarters. |

| 1130hrs | Percival sends deputation to make contact with the Japanese to arrange terms of surrender. |

| 1810hrs | Percival signs the capitulation document. |

At about 0800hrs on 12 February, 8th Brigade came under attack and for a while the Japanese were close to breaking through toward Nee Soon village and the Sembawang Airfield, only 2 miles from the naval base. The situation was eventually restored by a spirited counter-attack by 2/9th Ghurkhas from the 28th Brigade. Even so, the situation was critical here as well as in the Western Areas and Percival now decided it was time to withdraw all forces from the Northern and Eastern Areas and to form a defensive perimeter around the city. He envisaged a roughly hemispherical, nearly 30-mile long line that would stretch from Pasir Panjang in

the west to the race course, then east to Thompson village and Bidadari, then south to Geylang and finally south-west to the coast at the Singapore Swimming Club.

At noon, 11th and 18th Divisions began to move to their allotted positions, which was achieved with little interference from the enemy other than an attack from Japanese tanks at the Nee Soon/Mandai Road junction. Elsewhere, 22nd Brigade – now under the command of Brigadier Varley – had repelled several attacks but was clearly at risk of becoming isolated and withdrew successfully to their perimeter position, which forced 44th Brigade and 1st Malaya Brigade to adjust their own positions or leave their flanks ‘in the air’.

By early morning on the 13th the perimeter had been formed, but the area it described was now dreadfully congested. A steady tide of refugees had increased the population of Singapore city to about 1 million people and the concentration of service personnel and materiel within the perimeter was so great that there was hardly a space that did not constitute a legitimate military target for Japanese artillery and aircraft.

Combat continued throughout the day, including a determined action at Bukit Chandu on Pasir Panjang Ridge in which Lieutenant Adnan Bin Saidi won a posthumous Military Cross for his gallant efforts; however, the Japanese made modest but significant advances in several sectors, forcing the retreat of 44th Indian and 1st Malaya Brigades that night. At a 1030hrs meeting with Sir Shenton Thomas, the colonial governor, Percival made it clear that he still intended to carry on the fight, but the defensive perimeter was already under threat.

At 1430hrs on the 13th Percival called his subordinates to a conference at his headquarters at Fort Canning to discuss the prospects of the battle. Food supplies were now down to about seven days’ worth, but there were still reasonable amounts of ammunition available, though the anti-aircraft batteries were running rather low. None of those present expressed any confidence that a counter-attack was a feasible proposition.

Many of the front-line units were exhausted and a number had received little training and – especially 18th Division – no opportunity to adjust to the climate since they had arrived so recently. Although Bennett and Heath were in favour of surrendering, Percival maintained that the situation ‘… though undoubtedly grave, was not hopeless’, and decided to continue the battle. It is difficult, if not impossible, to see what hope Percival thought there might be. The Japanese were on the island in great strength with plenty of tanks, they had total air and sea superiority, their morale was high and they held the tactical initiative in every sector of the front. Percival was well aware that there was no relief force en route to Singapore, and there was no realistic possibility of holding out beyond a couple of days at most. Even if the arrival of a powerful relief force had been imminent, the power of the Japanese at sea and in the air would almost certainly have prevented it being disembarked and brought into action.

At 0830hrs on the 14th, 1st Malaya Brigade had come under attack and, though this was repelled, by 1600hrs they had been forced back to the Brickworks only a mile or so west of Mount Faber, which overlooked the western edge of the city. Although there were Australian artillery units in the area which could have provided support, General Bennett had given strict orders that Australian guns were only to fire in support of Australian troops due to the growing ammunition shortage. Clearly this was not going to be of any help if the battle as a whole was lost so it is difficult to see what Bennett could hope to achieve by conserving ammunition.

Although he was inclined to continue the fight, Percival realised that the end was in sight and that there was a limit to the value of further resistance, so he sent a signal to Wavell outlining the situation and asking for permission to seek terms when conditions deteriorated. Wavell’s reply was far from helpful:

You must continue to inflict maximum damage on the enemy for as long as possible by house-to-house fighting if necessary. Your action in tying down enemy and inflicting casualties may have vital influence in other theatres. Fully appreciate your situation but continued action essential.

Major General Woodburn Kirby,

The War Against Japan

,

HMSO, 1957

Clearly Wavell did not ‘fully appreciate’ the situation at all. Had he done, he would have understood that the campaign was over; that Percival’s troops could achieve nothing by fighting on and that the plight of the civilian population was becoming desperate. Furthermore, fighting to the bitter end would have no appreciable effect on the Japanese in other theatres. Hong Kong had already fallen, the Japanese were making good progress in Burma and the Philippines and the war in China would not be greatly affected by

transferring the relatively small numbers of troops in the Twenty-Fifth Army.

At 0930hrs on the 15th, Percival held another conference with his senior commanders, the Director General of Civil Defence and the Inspector General of Police. He was informed that shelling and bombing had caused extensive damage to the reservoirs and the distribution system, and that water supplies would last for forty-eight hours at best, and more likely only half that. Percival now accepted that there was no value to maintaining a defence since the Japanese were clearly capable of breaking his line at any point and decided that the only options were an immediate counter-attack or to surrender. His commanders’ opinions on a counter-attack had not changed since the previous meeting. Although there were still ample quantities of small arms ammunition, there was little for the field artillery, almost none for the anti-aircraft batteries and a shortage of mortar bombs for the infantry battalions. Additionally, the stamina and the morale of the combat troops was causing concern, as was the now widespread failure of discipline among other personnel. Percival could have chosen to follow Wavell’s orders and pressed his commanders to fight for every street and house. This would unquestionably have led to massive casualties among the residents as well as the combatants, but close combat of that nature tends to benefit the defenders, who have to be driven out of their positions by artillery and costly close attacks. It also demands the expenditure of very large amounts of ordnance, and Yamashita felt that he had neither the men nor the ammunition to conduct such a battle. He described his situation thus: