America I AM Pass It Down Cookbook (8 page)

W

e enjoy new tastes, textures, and creations,

but we also love the simpler foods from our pasts. Adding a modern spin on the traditional is inspiring and enriching for us.

In November 2008, we started a blog to share food cooked for friends, family, and ourselves. In a short time, the site transformed into an interactive platform with thousands of readers. In the beginning, we did not think about how our unique methods of cooking would evolve and what food would come to mean to us. That first post—pumpkin pie—was influenced by family traditions but with our own spin. Cardamom, amaretto, and a dash of cayenne for the filling, and nutty wheat germ in the homemade graham crust created a pie different from the ones we may have had before. Our cooking evolution had begun.

We grew up in dissimilar ways. Amir had a large family, and I was an only child. Although the action around the dinner table varied immensely between my quiet home in New Jersey and Amir’s busier childhood homes in Illinois and North Carolina, we both grew up appreciating food prepared at home.

That being said, the types of things that we ate on an average night were very different. Being health-conscious physicians, Amir’s parents prepared wholesome meals, making sure dinner was well balanced and nutritious. They left the grocery store with foods that were minimally processed and free of superfluous sodium and sugar. On the other hand, I came from a family of cooking convenience. We had canned vegetables, sauces, and dressings to accompany baked chicken or pork chops, pasta, and bagged salads. There were nights of Chinese take-out or cereal for dinner if no one felt like whipping up a meal. Even though the foods we ate in our respective families were different, it was always important in both of our homes that the family would sit down together to eat.

After college and separate moves across the country, Amir and I each developed our own style of cooking. Amir replicated his favorite dishes from home, using memory and taste as the main guides. I began to appreciate the taste of year-round fresh produce, herbs and spices, and preparing sauces and dressings from scratch. We both enjoyed walking through local farmers’ markets and pawing grocery store aisles for new ingredients to add flavor to our foods. We often think about how, in those days, we were most likely eating very differently from the majority of African Americans in their late 20s, but since then we have “virtually” friended like-minded African American food bloggers and cooks who have embraced organic, seasonal goods from local farmers’ markets, or even grow their own simple herbs in their small backyards.

As young urbanites, we may not have the space to grow vegetables and fruits like our ancestors, but we can easily pop a tiny herb garden onto the balcony or patio. We have also discovered the bounty available through Community Supported Agriculture organizations and directories. Being in touch with our food has most definitely affected the way we cook, as well as the cooking styles of many other young African Americans who strive to be more involved with the ingredients they use. The online community has responded positively to the ways we have taken recipes and made them our own.

We enjoy new tastes, textures, and creations, but we also love the simpler foods from our pasts. Adding a modern spin on the traditional is inspiring and enriching for us. We eat in the “in-between”—a place where what we love to cook rises from roots and creates new paths.

Amir and I have found that the way we move through the kitchen and develop unique recipes has been appreciated by our readers. We are often “applauded” for exploring neighborhood ethnic markets, investigating new flavors, and testing various means of fusion. Perhaps our readers will feel a bit less hesitant about their forays in the kitchen once they’ve seen our success—and even our failures. We do not attempt to hide any gaffes that may occur, as we believe that the good and the bad are both part of creating a meal. In the end, it’s our ability to stay true to our style of cooking, whether learned under the tutelage of grandmother or influenced by the televised words of Paula Deen, that allows us to stay true to ourselves.

What we both share is a strong love for food and cooking that has made us passionate eaters. It is that passion and interest that shapes how we have evolved and will continue to evolve. With food, we will carry on many of the traditions ingrained from years past as we forge on to create our own.

The Duo Dishes’ Honey Dijon Spiced Pecan Coleslaw

Los Angeles, California

SERVES 6 TO 8

Heart & Soul

There is very little mayonnaise in this coleslaw, but that is more than made up for by the combination of spices that are used.

½ medium red onion, minced

16 ounces shredded cabbage

1 carrot, shredded

¼ cup Dijon mustard

1 tablespoon mayonnaise

1 tablespoon apple cider vinegar

1/3 cup honey

zest and juice of ½ lemon

1 teaspoon caraway seeds or celery seeds (optional)

½ cup pecans, chopped

½ tablespoon brown sugar

½ tablespoon white sugar

½ tablespoon unsalted butter

½ teaspoon cayenne pepper

¼ cup dried cranberries

kosher salt

Mix onion, cabbage, and carrot in a large bowl.

In a separate, smaller bowl, whisk mustard, mayonnaise, vinegar, honey, lemon juice and zest, and caraway seeds. Season to taste with salt. Pour dressing over coleslaw mix. Toss well then chill in the fridge.

As slaw chills, add butter to a pan. When melted, toss in pecans. Sprinkle with cayenne and brown sugar and toss to coat. Slide onto parchment paper- or wax paper-covered sheet and pop in the freezer until completely cooled.

When ready to serve, add spiced pecans and cranberries to slaw and toss to combine.

The Duo Dishes’ Cornbread Panzanella

Los Angeles, California

SERVES 4 TO 6

Heart & Soul

This salad turns cornbread, an everyday staple in soul food cooking, into an elegant, Italian-inspired salad.

3 cups leftover cornbread (

page 42

), cubed

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

1 pint mixed cherry tomatoes, halved

1 medium red onion, diced

1 cucumber, peeled, deseeded, and diced

10–15 fresh basil leaves, sliced

1/3 cup olive oil

¼ cup balsamic vinegar

½ tablespoon Dijon mustard

zest of 1 lemon

1 tablespoon maple syrup

kosher salt

Melt butter in an oven-safe pan or heavy skillet and add cornbread. Toss cornbread in butter and cook over medium high heat for 3–5 minutes. Toast in a preheated oven at 300° F for 10–15 minutes or until dry and hard like croutons. Remove from oven and set aside until cool.

Whisk together olive oil, balsamic vinegar, mustard, zest, and maple syrup. Salt to taste.

In a large bowl, toss cornbread with tomatoes, onion, cucumber, and basil. Drizzle with 1/3 to ½ of the dressing and serve the rest on the side.

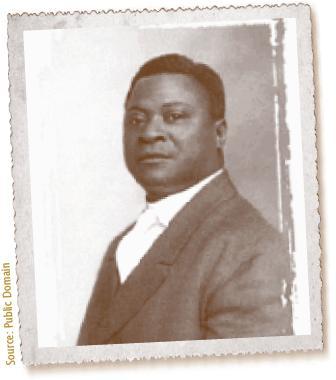

Rufus Estes

Rufus Estes was born eight years before the end of slavery, in Murray County, Tennessee. In 1867, after Emancipation, he and his mother moved to Nashville, where he attended a term of school before having to work to help his ailing mother. He was just 10 years old. By the time he was 16 he got a job working in a Nashville restaurant and two years later found his way to the Pullman Company as one of hundreds of black workers who served as porters, cooks, and janitors on the railway cars that criss-crossed the country.

It was as a Pullman cook that Mr. Estes gained a reputation for culinary skill. His way with food was so prized that he cooked for (or “cared for,” as he said in his own words) two presidents, royalty, and famous actresses, composers, and explorers of the day. His book

Good Things to Eat

is a compilation of his famous recipes published in his own words in 1911. It is possibly the earliest published cookbook by an African American man and to this day remains a canon of good things to eat.

“One of the pleasures in life to the normal man is good eating, and if it be true that real happiness consists in making others happy, the author can at least feel a sense of gratification in the thought that his attempts to satisfy the cravings of the inner man have not been wholly unappreciated by the many that he has had the pleasure of serving—some of whom are now his stanchest friends. In fact, it was in response to the insistence and encouragement of these friends that he embarked on the rather hazardous undertaking of offering this collection to a discriminating public.”

— from the Foreword to

Good Things to Eat,

Rufus Estes, 1911.

These three recipes, adapted from

Good Things to Eat

, make use of three types of corn that were and are a staple in the soul food kitchen.