America I AM Pass It Down Cookbook (3 page)

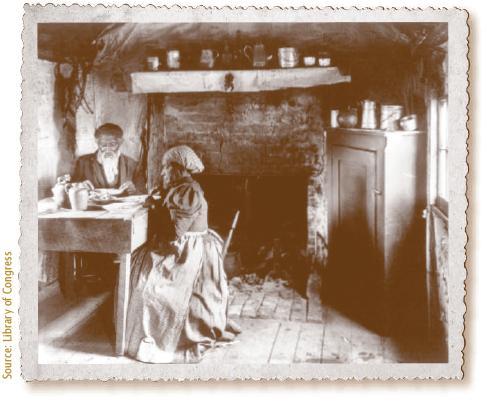

An elderly African American couple has a solemn meal in their tidy rural Virginia home in 1864, during the Civil War.

Many Northern states had pre-Emancipation communities of free African Americans. Massachusetts, for example, had abolished slavery by 1783,

16

and New York fully in 1827.

17

While these free blacks had business owners, lawyers, teachers, and ministers among them, there were still many who were hired as housekeepers and cooks.

18

It was these African Americans in the North, including those who escaped captivity, who would also help solidify the national imprint of African American cooking methods. And as more black Southerners moved North during and after the Civil War, and again as part of the early 20th-century Great Migration, dishes that were once considered solely the domain of the South became as commonplace in Chicago as they were in Charleston.

As African Americans populated states outside the South, their soulful recipes from back home were passed down from generation to generation. Whether through storytelling or handwritten recipes, these heirlooms included everything from secret cooking ingredients to special ways of kneading dough for monkey bread.

19

These culinary inheritances allowed Southern cuisine to become a living tradition across the country.

What If There Were No African American Imprint on Food?

It’s hard to imagine this nation without the African American culinary imprint. There would be no more eating grandma’s signature fried chicken at Sunday dinners. No more steaming plates of chitterlings and black-eyed peas on New Year’s Day. No more family reunions with passionate contests between relatives to see who created the spiciest or most savory barbequed ribs. No more getting your soul filled with soul food.

Stirring the Melting Pot

Foods made by African Americans with African cooking methods and transplanted African foods have existed for centuries in America, yet the use of the term “soul food” to describe African-inspired Southern dishes did not occur until the 1960s. But whether you call it soul food or Southern cooking, this food imprint is an integral part of American cuisine.

As a result, the African American food imprint continues to inspire America’s imagination and please taste buds

.

From Thanksgiving Day platters of candied yams on dining tables across the country to the availability of canned collard greens and packaged cornbread at the supermarket, from barbeque joints in Manhattan and Seattle to Southern-born fried chicken franchises in cities and towns across America, the gastronomic descendents of those foods and recipes introduced by enslaved Africans are welcomed in every home and in every state. The African American culinary imprint has become an indelible part of American cuisine that continues to stir our melting pot and nourish the heart and soul of this nation every day.

Then as now, Sunday was a day not just to worship but to gather, socialize, and spend a little time relaxing that often lasted the whole day and into the evening. Talented cooks, both male and female, lent their hands to feeding crowds either by potluck or marathon cooking sessions in the church or meeting house kitchen. One-pot dishes, like Brunswick stew, burgoo, jambalaya, or gumbo that could feed a crowd for little money always had a place at the table.

CHAPTER

1

Starters,

Soups & Salads

Nicole Taylor’s Backyard Pecans with Rosemary

Brooklyn, New York

SERVES 4 TO 6

Atlanta-raised Nicole Taylor is the host of

Hot Grease

on the Heritage Food Radio Network. These aromatically spiced pecans were born from her fond memories of picking pecans in her family’s Georgia backyard as well as Thanksgiving and Christmas parties that remind her of “passing the nutcracker and pecans around the room.” They are, says Ms. Taylor, her favorite pre-meal nibble or anytime snack.

2 cups Georgia pecans

1 teaspoon (heaping) coarse salt

½ teaspoon cinnamon

4 tablespoons unsalted butter

¼ cup dark brown sugar

1 tablespoon chopped fresh rosemary

Pass It Down TIP

This spicy, sweet snack is a perfect carry-along for your lunch bag.

Toss pecans in large skillet over low-medium heat. Toast around 10 minutes. Set aside in small mixing bowl.

Combine cinnamon and salt. Set aside.

Melt butter in skillet over low-medium heat. Add sugar and rosemary, stir until golden brown. Add pecans to the skillet and coat well.

Transfer to small mixing bowl. Sprinkle with salt mixture and toss. Place in festive bowl and provide cocktail napkins.

Justin Gilette’s Low-Country Crab Cakes

Atlanta, Georgia

SERVES 4 TO 6

Justin Gillette’s knack for cooking began after a baseball injury forced him to choose a different elective course in 10th grade. He chose a culinary class. Today, Gillette, a 26-year-old self professed foodie who works full time as a chef for the food service company Sodexho, is intrigued by every facet of the culinary world. He has traveled internationally, soaking in the culture and cuisine of Portugal and Spain, from Madrid, Seville, and Segovia to the southern tip of the Costa del Sol, to Morocco in North Africa, and Alaska. His style of cooking can be described as the low country type, but similar to New Orleans cuisine. It’s flavorful and robust, much like food cooked in Charleston and Savannah, but with a spin of French and Spanish cuisine around the edges.

2 tablespoons butter

¼ cup small onion, chopped

2 teaspoons fresh thyme

¼ cup diced celery stalk

1 teaspoon salt

2 teaspoons ground black pepper

1 cup mayonnaise

2 tablespoons Dijon mustard

4 shakes of Tabasco sauce

1 teaspoon celery seed

½ teaspoon cayenne pepper

3 teaspoons sugar

2 large eggs

1 pound lump crab meat

1 cup bread crumbs

2 cloves garlic, chopped

Pass It Down TIP

Crab cakes freeze easily and can keep up to six months when stored properly. Double or triple this recipe and freeze the extra cakes for a last minute party, brunch, or special appetizer. Simply form the raw crab cakes and place them in a single layer on wax paper inside a freezer-safe, sealable container. Place another sheet of wax paper on top of the crab cakes and add another layer of crab cakes on top. Seal tightly and freeze. To use: Remove crab cakes as needed and defrost in the refrigerator in a sealed container. Once defrosted, cook crab cakes as you normally would.

In a hot skillet, melt 1 tablespoon of the butter. Add the onions, garlic, thyme, and celery. Sauté until the mixture becomes translucent. Set aside to cool.

In a bowl, mix the mayonnaise, mustard, Tabasco, celery seed, cayenne pepper, sugar, and egg. Mix until thoroughly combined.

Add the cooled onion mixture to the bowl and mix well. Gently fold in the crab meat. When completely mixed, add the bread crumbs to bind the mixture together, adding more as needed to achieve a moldable consistency.

Form the crab meat mixture into small patties, about 3–4 inches in diameter. Place on a tray lined with parchment. Chill in the refrigerator, covered in plastic wrap, for at least 1 hour and up to 8 hours.

Heat the remaining tablespoon of the butter in a skillet on medium-high heat. When melted, place the crab cakes in the pan and cook on each side until golden brown—about 5–8 minutes. Serve with Remoulade Sauce (

page 231

).