America I AM Pass It Down Cookbook (2 page)

Similarly, the America I AM

Pass It Down Cookbook

is filled with recipes that reflect the generations-long need to document and share our history and culture. As African American people, it is imperative that we record our culinary contribution to America’s kitchen. The recipes in this book are accompanied by personal stories that provide us with a unique opportunity to preserve our cooking heritage. Yet all of these recipes would mean much less if they didn’t have a genuine connection to the heart and soul of our contributors.

As I traveled across the country gathering recipes and preaching about the importance of “passing it down,” I met many amazing people who shared their recipes and food stories. In Atlanta, while shopping in a Publix for ingredients for a cooking demonstration at the National Black Arts Festival, I struck up a conversation with an elderly white woman. She was navigating her way with her electric scooter toward the baking section, where our casual conversation rapidly turned to Southern cooking.

We talked about canning peaches and the best way to cook collard greens using scrap meat. She even told me quite emphatically that fried chicken is best if cooked in pork fat. Wow, I thought, that’s very interesting. Our cook-to-cook exchange reminded me that Southern whites

’

cooking was not radically different from Southern blacks’ cooking because we helped to define the region’s food. While not everything she said was new or something I’d do in my own kitchen, I was really touched that she would so readily pass along such personal advice.

For centuries, it was this kind of sharing that kept African Americans going. On a daily basis, family and friends came together for the main meal of the day and for conversation, and it was in this environment that such kitchen wisdom was exchanged. Growing up in poverty, supper was the one daily event that put a smile on our faces. No matter how poor folks were, supper was often grand. We’ve lost a lot of traditions, but keeping my family close during Sunday Supper is one ritual that I try to hold on to. There are other, smaller customs that still connect me to my family as well. Just like my grandparents, I’ve always had an old mayonnaise jar in the freezer filled to the rim with seafood gumbo, or several casserole dishes in the refrigerator. Many dishes I serve today come from my experience as a chef, but the meals served from the Henderson’s family table have become the foundation of my cuisine.

How to Use This Book

Filled with poignant memories of the past, and the present triumphs of both the acclaimed and unknown black Americans who impacted the way the whole nation eats, this book also gives voice to everyday people and their triumphs in the kitchen. Through their recipes we sit at their tables and hear their tales of family, friends, their past, and their future.

This volume, like any other traditional cookbook, is arranged according to recipe categories, with like ingredients grouped together; however, its greatest value is in the extras you’ll find on every page. Pass It Down Tips & Tricks, time-saving ideas, and healthy alternatives make cooking easier and healthier, while Did You Know? boxes educate and delight. Dishes that are as great for your waistline as they are to eat are marked with a “Heart and Soul” stamp of approval.

The

Pass It Down Cookbook

also explores how African Americans have impacted the economy, the iconography, the preparation, and the very spirit of American foods. Nowhere is this more skillfully reflected than in the contributions of our essayists: In “Presidential Cooks,” Adrian Miller explores the impact both enslaved and free Blacks wielded in the White House kitchen; Michael Twitty discovers the depth of his African American food roots through Judaism in “Finding My Way Home”; my co-editor Ramin Ganeshram’s “Taking Back the Table” reveals how food and the sting of segregation became a catalyst for her father’s activism; Donna Daniels presents a heart-warming story of how her sister expanded her family’s worldview through food; Michele Washington’s “Ironic Authority” takes on the smiling fictions of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben; and Desmonette Hazly discusses the culinary arts as a vehicle for social change in “Sacred Table, Sacred Feast.”

We are particularly proud of our Pass It Down Menus that can help readers assemble a casual gathering or a spectacular celebration by pairing recipes from this book. From Easter Sunday Brunch to the Festive Winter Holiday Gathering and the Anytime Ice Cream Social menu, you’re certain to find a menu that suits your taste buds to a tee.

Our goal was to create a collection that is both a cookbook and community memoir filled with great food and even better stories. There’s something for everyone—even the kids, who will love it when they can cook at your side using Chef Scott Alves Barton’s special kid-friendly recipes. The younger generation will also be inspired by the special section featuring up-and-coming chefs. And of course, the book would not be complete without pages where you can record your own recipes and “pass it down” to future generations.

So what’s the best way to enjoy the riches of the America I AM

Pass It Down Cookbook?

By looking—and looking again. We’re sure that every time you pick it up you’ll discover something new in its pages.

We hope, as you read this book, it will become a way to learn about and share the bounty that is the African American contribution, not just to food, but to the very identity of this nation. Turn the pages and join us at the table. After all, our shared experience is the greatest feast of all.

— Jeff Henderson

Stirring the Melting Pot:

The African American Imprint on Cooking and Food

BY JOANNE MORRIS

As a member of the creative team behind Tavis Smiley’s award-winning America I AM: The African American Imprint exhibit, Joanne Morris wrote select elements and oversaw production of the exhibit’s eleven multimedia components and its sound design. Morris has written and produced projects for BET, NBC, Fox, and others. She’s also written and produced plays directed by famed filmmaker Charles Burnett.

S

weet candied yams.

Savory collard greens. Warm cornbread. Tender ribs lusciously covered in barbeque sauce. Oven-fresh cobbler baked with succulent peaches in a brown sugar nirvana topped with a heavenly crust.

These are just some of the delights of Southern cuisine, known today around the world as

soul food.

While soul food is familiar to many, what is often not recognized is how thoroughly the rich, diverse African American culinary imprint has been stirred into America’s melting pot of food. This essential contribution is one of the significant imprints—alongside art, literature, politics, music, and much more—celebrated in the national traveling exhibition, America I AM: The African American Imprint

.

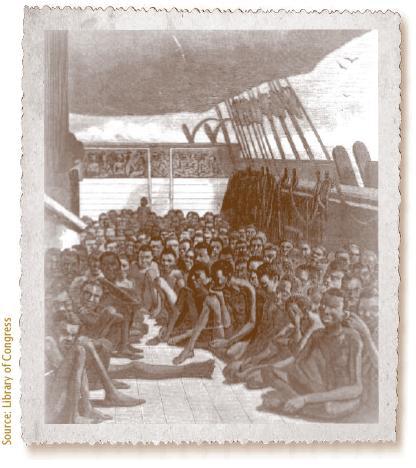

On slave barques like the Wildfire, depicted here, foods were used to degrade, cajole, and control African slaves, precious “cargo” though they were.

With its centuries-old roots grounded in West and Central African cultures and diets, the culinary imprint can still be seen today, whether in choice of ingredients, cooking techniques, or delicious recipes. For instance, both the peanut synonym

goober

1

and the name of the famed Creole dish

gumbo,

2

which means “okra,” have their origins in the Bantu language family of Central and Southern Africa.

3

And did you know that African barbeque used a flavorful sauce that has become a staple of American grilling cuisine? Or that the old-fashioned version of gingerbread cake derives from a Congolese cake made with dark molasses and ginger-root powder?

Are There Really American Foods of African Descent?

You may be surprised to know which foods were brought to this country through the transatlantic slave trade.

4

Centuries later, we still find some in pantries and on kitchen tables across the country, from sesame seeds and black-eyed peas to peanuts. Originally brought to Africa from Brazil by Portuguese slave traders, the popular peanut was introduced to the colonies through the slave trade. Likewise, yams and watermelons, both specific to African agriculture, traveled across the same ocean route to prosper in Southern soils.

Another food item in American cuisine that benefited from African influence is one we don’t readily associate with either Africa or America—rice. In fact, just as cotton and tobacco were cash crops cultivated by enslaved labor, which generated millions of dollars for this nation’s colonial and pre–Civil War economies, rice played a major role in the agricultural development of America. Successful rice cultivation was the direct result of the agricultural know-how of enslaved Africans and their American-born descendants.

5

African rice farmers—of which a significant number were women—from areas such as Angola and Senegambia were often targeted by slave traders because of their expertise.

6

Today, rice not only remains an American food staple, but the United States is the fourth largest exporter of rice in the world.

7

Clearly, the hands-on role of enslaved African Americans in planting, growing, and harvesting food, particularly in the South, helped to define the emerging American cuisine. But the imprint would be greatest in how these foods were prepared.

Did the Collision of Cultures Impact the Imprint?

Though enslaved Africans were living in the Spanish colony of St. Augustine, Florida in the late 1500s, the virtual seeds of the African American culinary imprint were planted in August 1619 with the arrival of the 20 African men and women in England’s first permanent colony in Jamestown, Virginia.

8

Over the centuries, the African American population would grow into thousands and then millions.

9

Among them were West and Central Africans from hundreds of culturally diverse tribes, who spoke just as many languages.

It was the collision of cultures—West and Central African, European, and Native American populations—that created the foundation of American culture and cuisine. However, with enslaved blacks outnumbering the white population in many places, the African American food imprint often dominated because, as Jessica B. Harris has noted, they “planted it, grew it, harvested it, cooked it, served it . . .” (

Iron Pots & Wooden Spoons

:

Africa

’

s Gifts to New World Cooking).

Although Africans who were captured and sold into slavery could not bring their possessions to America, they brought their cultural memories, which included how they prepared foods. These cooking techniques were used both in the slaveholder’s kitchen and in the slave quarters where they cooked for their own families.

10

One of these techniques was deep-frying—with peanut oil or lard—which, over time, became a standard method in American cooking.

11

In fact, this African practice led to the elevation of a staple food of African descent to an American classic—fried chicken. Enslaved Africans applied several cooking methods to create dishes that are American favorites to this day. For example, they adapted how they made

eba

12

to hominy, turning it into glorious grits, and how they baked

fufu

13

is the same way they made cornbread.

As noted earlier, barbeque sauce is another African culinary import. Africans had their own style of barbeque that incorporated a sauce made of chili and sweet peppers. The Timucua Indians of Florida were recorded cooking meat using the

barbacoa

method by European colonizers as early as the 1560s. These influences would combine to form this unique Southern style of cooking.

The influence of African culture on the American palate is well documented in both history books and cookbooks. From the shores of West Africa to the plantation kitchens of the American South, the foods and ingredients they used are entwined in American cuisine and can now be found on the menus of restaurants around the country.

The African American Food Imprint in the North

Once in America, the people stolen from West and Central Africa represented the breadth of social backgrounds—from aristocrats to artisans, farmers to soldiers.

14

They were sold throughout the Southern and Northern colonies alike until the early 1800s. Slaves in Northern urban areas were often not confined to service in the master’s house. These workers would often be sent to sell food on the street, making extra money for their slaveholder.

15

It was enslaved street vendors who took their home cooking, influenced by their African heritage, into the streets of America’s growing cities.