America I AM Pass It Down Cookbook (5 page)

Pass It Down TIP

Store vegetable, meat, and bone trimmings in freezer-safe baggies, with dates clearly marked, to use for making stock.

Chef Jeff’s Collard Green Soup with Smoked Turkey

Las Vegas, Nevada

SERVES 6 TO 8

There are many ways to cook greens. Some great home cooks use three types: collards, mustards, and turnips. Chef Jeff took the collared green recipe from his big sister, turned it into a soup, and then put a healthy spin on it. “I once served this soup at a National Heart Association conference. The participants still write to me to tell me how much they loved the recipe.

8 cups of fat-free, low-sodium chicken broth or homemade stock (see recipe

page 13

)

1 tablespoon garlic powder

1 small smoked turkey drumstick

1 medium yellow onion, diced small

1 bunch of organic collared greens, stems removed and roughly chopped

5 cups purified water

salt or salt alternative to taste

freshly ground white pepper to taste

In a stockpot over medium heat, add chicken broth, garlic powder, and turkey drumstick.

Sauté onion until translucent—don’t let it burn—then add onions and greens to stockpot and pour in the water. Reduce heat to a simmer. Cook for 1 hour or until greens are tender.

Remove turkey from pot. Let turkey cool and then remove meat from bone. Roughly chop meat and set aside. Season with salt (or salt alternate) and white pepper to taste.

Remove greens from broth and set aside. Strain broth and put back into the pot.

Season with salt or salt alternative and pepper to taste.

Pour broth into bowls. Add turkey and greens.

Pass It Down TIP

This is a delicious soup to serve year-round. Turkey is used as a healthy alternative meat for this recipe. It adds great flavor to the soup.

Finding My Way Home

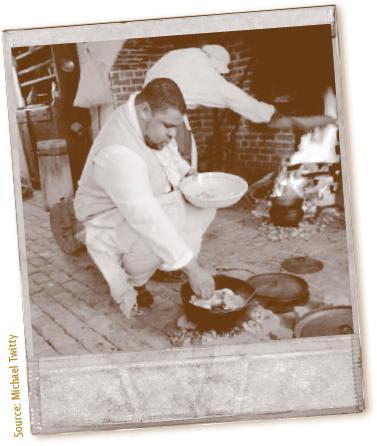

BY MICHAEL TWITTY

Michael Twitty is a native of Washington, DC who learned to cook from watching his grandmother and from the patient teaching of his mother. Today he is a recognized food historian who takes recipes from the past and uses heirloom, organic, and heritage-breed ingredients to re-create historic and traditional dishes that are part of what he calls “our own edible jazz.” Twitty was instrumental in helping the D. Landreth Seed Company, which has been in business since 1784, develop a catalog of African American heritage seeds released in 2009. He is the creator of

www.afrofoodways.com

, the first Web site devoted to the preservation of historic African American foods and foodways.

A

t age seven,

I read Chaim Potok’s book

The Chosen

, the story of the binding friendship between two Jewish boys in Brooklyn, New York in 1940. I was utterly fascinated—an exploration my mother indulged by allowing me to “be Jewish” for a week, which ultimately amounted to me not eating any pork. But the book and the strong tie to religious culture stayed with me, and in 2002, at age 25, I converted to Judaism.

When I became Jewish, my whole worldview as an African American and my take on African American culture changed. I thought I couldn’t have any more respect or love for my roots, any deeper sense of pride—and converting to Judaism, in my case, changed that. Far from removing me from my heritage, it brought me closer to the stories and lives of our ancestors.

“It’s not easy

putting on the garb of an

enslaved person and cooking

in the same kitchens that fed the

families of the planters or in the few

remaining slave cabins that dot the

landscape; but when I remember I’m

doing honor to the forgotten chefs

who invented Southern

cooking, it sweetens

the experience.”

Here I was, confronted with a religious culture that used food repeatedly as an edible textbook—to transmit history, ethics, culture, geography, customs, and family traditions. The Passover Seder is all about using food to tell the story of slavery and redemption from slavery. That sent me back into the world into which I was born looking for the culinary genealogy that was my birthright. I had to teach the Holocaust in Hebrew school, and I wanted to soften the lesson with something more palatable, so I chose a book called

In Memory’s Kitchen

by Cara De Silva. She wrote about the women of Terezin, Hitler’s “model” ghetto/concentration camp, and how they recalled their prize heirloom recipes even in the midst of hell.

It hit me: What if enslaved Africans—the oldest cooks in human history— and their descendants could have such a record, told in food, of their struggle to survive, persevere, overcome, and be free? That’s what set me on my journey.

Tracing the roots of our food from West and Central Africa to the present day through enslavement has not been easy. I have forced myself into the cotton, rice, tobacco, and cornfields to experience a taste of the brutality that made our cuisine in chains so precious at the end of those “can to can’t” working days. It’s not easy putting on the garb of an enslaved person and cooking in the same kitchens that fed the families of the planters or in the few remaining slave cabins that dot the landscape.

But when I remember I’m doing honor to the forgotten chefs who invented Southern cooking, it sweetens the experience. I want African Americans as a people to embrace our heirloom produce, our traditional foods, and the recipes that can and will be lost if we don’t reclaim them and own them as part of our legacy. Jewish tradition tells you to “Bless the Lord and eat and be satisfied.” African American tradition bids us to “sit at the welcome table.” By weaving those traditions together I’ve found my way “home.”

Michael Twitty’s Heirloom Cowhorn Okra Soup

Baltimore, Maryland

SERVES 4 TO 6

“Cowhorn Okra Soup is just one example of the music of soul food,” writes Michael Twitty.“From Senegal to Angola, from Jamaica to Haiti, and later from Baltimore to Savannah to New Orleans, one traditional soup stands out as a reminder of the undying connection to West and Central Africa. Known as supakanja (kanja or kanjo means ‘okra’ among the West Atlantic speakers of Senegambia and Sierra Leone) in West Africa, okra has many names along the coast from which our ancestors came. This recipe was popular on both the table of the plantation owner and his enslaved workforce along the entire southeastern seaboard and Gulf coast. Cowhorn okra, a crisp heirloom variety is rooted from okra seed brought to America during the slave trade. This recipe is over 250 years old.”

2 medium yellow onions, sliced or chopped

3 tablespoons flour

2 or 3 tablespoons bacon drippings, lard, vegetable oil, or butter

2½ quarts of water

1 dried or salted fish that’s been soaked overnight

or

1 cup salt pork or bacon pieces or smoked turkey (see vegetarian option below)

3 cups tomatoes, chopped

2 pounds okra, sliced

1 long red cayenne pepper or Maryland Fish pepper, sliced in half

herbs of your choice (bits of parsley, rosemary, basil, etc.)

salt to taste

1 cup cooked crabmeat (optional)

Heat the oil or drippings until hot but not smoking.

Dust the onions in the flour. Add them to the pot with the heated oil and sauté until translucent. Add the water and choice of meat and cook for 2½ hours. This creates the stock for the soup.

Add the remaining ingredients and simmer another 2 hours.

Pass It Down TIP

You can make this dish using fresh chicken to replace the other meats. Simply lightly brown the chicken with the frying onions, then add enough water to cover it by 1 inch. Simmer for 2½ hours. To make this a vegetarian dish, ignore the meats and replace the water with vegetable stock, preferably organic.

Apryle’s Seafood Gumbo

Charlotte, North Carolina

SERVES 10

Rhonda Dorsey-Prude is an Army veteran who says that, while she loved good food, she was never that good in the kitchen. But time and practice changed all that—along with a few must-have recipes gained from friends and family, like this one from her sister Apryle. It forgoes both roux and the holy trinity of Louisiana gumbo—pepper, onion, and celery, proving what a versatile and adaptable dish gumbo is. Ms. Dorsey-Prude remembers the first day she had Apryle’s seafood gumbo back in 1987 and how intent folks were on getting every last delicious drop from their bowls.“The table was so quiet it was crazy,” she says. “You heard spoons hitting against the porcelain.”

3½ cups plain tomato sauce

10½ cups of water

1 teaspoon gumbo filé (powdered sassafras leaf)

2 teaspoons Old Bay Seasoning to taste

1 pound andouille sausage, sliced into ½-inch rounds

1 pound medium sea scallops

1 pound lump crab meat

1 pound fresh oysters

4 ears corn, halved

2 pounds medium shrimp, shelled and deveined

6–8 okra, chopped

Bring tomato sauce and water to a boil in a large stockpot with the gumbo filé. Add the Old Bay Seasoning to taste.

Simmer 45 minutes. Add the andouille sausage and all seafood except the shrimp. Remove the ends of the okra, dice them, and add them to the pot. Continue to simmer for another hour.

Add the corn in the last 20 minutes of cooking, and add the shrimp in the last 15 minutes of cooking. Turn off the heat and allow the gumbo to sit 20 minutes before serving, stirring every 5 minutes.

Serve over white rice.

Did you know?

Gumbo filé is powdered sassafras leaves and was used for both medicine and as seasoning for soups and stews among Native Americans.