Adrift (8 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

Quickly rummaging through my emergency bag, I claw out the spear gun and arrow. Wait ... what if it is a strong fish? I hurriedly tie a piece of line through the gun handle and onto the raft. My stomach growls. Four days on a pound of food. I'm trembling with excitement.

I must watch the waves. With my weight on the low side, a breaker might easily capsize us. At times I must leap back to windward and hang on until the foaming eruption subsides. Meanwhile I observe the dorados. They are three to four feet long and must weigh twenty to thirty pounds. Their power will make them difficult to catch. A sailor in the Canaries once told me of a dorado that knocked a boat's cockpit to pieces, including a bolted-down steering-wheel pedestal. A continuous dorsal fin stretches from the squared-off head down the aquamarine back to a bright, yellow-finned tail. It is their tails that are visible from far away, piercing the surface as they bodysurf down waves. These fish are widely renowned for agility, strength, beautyâand good eating.

I've never caught one or even seen one in the ocean before. The sea is obviously not a threat to

them.

It is their home, their playground. A few cruise by about six feet away, just out of range. But in their curiosity they swing close every now and then. Surface refraction makes it difficult to aim, and the lurching raft is a poor platform from which to shoot. My few attempts miss widely. Hunger continues to gnaw as the sun sets.

Another two days bring more sun, wind, sea, and dorados. Leaping out of the sea in ten-foot arcs and landing on their sides, they look like agile, breeching whales. I'd drool if only my mouth could summon more than sticky saliva. "Come my beauties, come just a bit closer," I coo to them. But when they approach, my spear misses the mark.

My mind creates fantasies of food and drink and turns continually back to

Solo,

to the pounds of fruits, nuts, and vegetables and the gallons of water within her. I see myself opening lockers and pulling out food. I plan how I might have saved her, shifted stores, dumped ballast, raised her in midocean to sail again. What if we hadn't become separated? What if we hadn't left the Canaries? What if ... Stop it! She's gone. Concentrate on

now,

on survival.

Once again I try one of the solar stills. As it sails forward, its water collection bag drags behind on the surface. This prevents the fresh water from draining into it. So I must frequently empty the balloon of a small amount of water. The day's total is one-half pint. Seas continue to batter the still until the tabs that hold its tether are ripped off. I often dump out the water to find it is salty. My body's craving for water is building. I would give anything for a drink, but can only afford an occasional mouthful. I open my first can of fresh water. Five pints left, maybe fifteen days to live if I can catch fresh fish to supplement my fluid intake. Otherwise I may have as little as ten days left.

At least things are drying out and at night I can sleep. I escape through dreams. Each hour I awake to my prison, my hair pulled out by the chafing rubber, my joints aching for the chance to stretch out.

FEBRUARY

10

DAY 6

On February 10, my sixth day in the raft, the wind blows hard as the Atlantic continues "the shuffle," a term sailors use for the commonly confused wave patterns of the Atlantic. Ridges of waves approach from the northeast, east, and southeast. They break on three sides of the raft, tumbling it about in a nonstop rock-and-roll dance. At least we are headed more westerly, more directly toward the West Indies.

But with each good thing comes the bad. The repair to the floor has come up, and after hesitating to use some of the last patching equipment, I manage to seal it. I feel weak. The still produces only salt-ridden water, and I argue with myself not to drink more than one-half pint of my reserve each day. The dorados are beautiful but tease me by staying just out of range with quick evasive maneuvers. One passes close by and I fire. The spear jerks my arm straight. It's hit! The raft twists around. Then the fish is gone. The silver arrow lies limp, dangling from the end of its rope, too weak to drive through these fish. Hunger is eating my fat, then it will eat my muscles, then my mind.

T

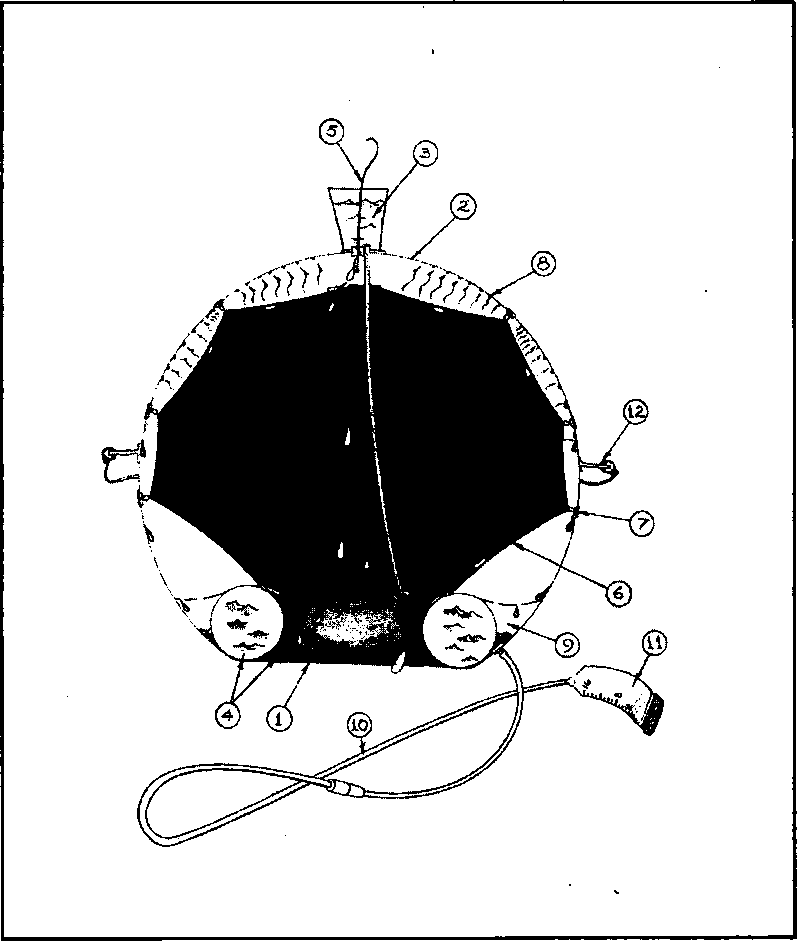

HE SOLAR STILL.

The stills that I use are military surplus models. They are no longer manufactured, but other stills work on similar principles. My stills are rated to produce a maximum of thirty-two ounces of fresh water per day, a two-day survival ration. I get thirty ounces on the best days and often as little as sixteen.

A cloth bottom (i) allows excess seawater to seep through. When wet, it is airtight and allows the plastic balloon (2) to be inflated. Seawater is poured into the reservoir (3) on the top. The first half gallon drains down a tube into the salt water ballast ring (4). Additional seawater drips from the reservoir through a tiny valve. A jiggle string (5) keeps the valve free and helps regulate flow. From the valve, the seawater drops onto a black cloth wick (6). The wick is suspended from the sides of the balloon by attachment loops (7), which keep the wick away from the balloon; otherwise salt water from the wick will drain onto the balloon's inner surface and pollute the distillate. The black wick becomes saturated with seawater. Some of the seawater evaporates. The vapor, shown by squiggly arrows, collects as small drops of fresh water (8) on the inside of the balloon. The drops trickle down to the fresh water, or distillate, reservoir (9). From here the water drains down a tube (10) into the distillate collection bag (11). The tube is equipped with a fitting that allows removal of the bag for emptying. The bag is weighted with a piece of lead for proper drainage. A skirt and lanyard (12) pass around the middle of the still. Although the still is designed to be used in the water, I must use mine aboard the raft.

I bend over the tubes and look down deep into the sea. There are no fish, no weeds, only empty blue. Have I missed my only chance to catch food? Have they gone? Suddenly a shape appears forty yards to the side, gliding with incredible speed right for the raft. A ten-foot beige body with an unmistakable broad hammerhead tells me all I need to know. Man-eater. No dorsal fin rips through the water. Its long, sleek torso needs hardly move to thrust itself ahead. My heart pounds. I hold my spear tightly. If I shoot I will lose the arrow. I gaze at the shark sliding under me just below the surface. Making a smooth, tight corner, it circles back, faster now. As if accelerated by centrifugal force, it closes in on the raft. My mouth is dry, my arms shake; cold sweat streams from my skin. A complete circle executed, the beast thrusts into the wind and melts into the blue as quickly as it came. The vision will last forever. How often will they come? I will never dare to swim from the raft.

I wonder about God. Do I believe in Him? Somehow I cannot accept a vision of a super humanoid, but I believe in the miraculous and spiritual way of thingsâexistence, nature, the universe. I do not know the true workings of that way. I can only guess and hope that it includes me.

Nothing seems to hold a future. The horseshoe preserver chafes on the raft tubes. I am already pumping air into them four times a day to keep them properly inflated. Additional wear can mean disaster. I decide to use the float to make "bottles" and to write messages for my bottles. I cut the float in half, spewing snowy styrofoam nubs all around the raft, wrap my desperate letters in plastic bags, and tape them to the styrofoam blocks. "Situation poor, prognosis worse, approximate position ... direction and speed of drift ... please notify and give my love to..." I cast them out upon the waters and watch them tumble southward. Perhaps someone will see them. If

Solo

lives, there are four remnants of me that can be found.

FEBRUARY 15

DAY 11

It is my eleventh day in the raft. Each day passes as an endless age of despair. I spend hours evaluating my chances, my strength, and my distance to the lanes. The raft's condition seems generally good, although the tent leaks through the observation port when nearby waves break. One night we shot down the front of a big roller, for several seconds sliding upon its tumbling foam as if we had fallen over a waterfall. Then last night we nearly capsized again. Everything is soaked. Today, though, a flat, hot sea surrounds me. The sun beats down on the wide expanse of this liquid frying pan and things begin to dry out once more. The sun and sedate sea are welcome.

My scabs are torn off or wiped away when my skin is wet. With the sun they will heal, eventually. Most of the salt water boils have vanished. There is a great emptiness in my stomach, a cramped, incessant yearning. It visits me each night in my dreams. Fantasies of hot-fudge sundaes with numerous varieties of ice cream dance through my head. Last night I nearly got to taste hot buttered whole-wheat biscuits, but they were snatched away from me when I woke up. And how many hours have I spent back on

Solo,

collecting the dried fruit, the fruit juices, the nuts? Hunger is a witch from whom there is no escape. Her spells conjure these visions of food and deepen the pain. I look at my stock. The can of beans is blown. I dare not eat them for fear of botulism. Then again, maybe they're all right. Quickly now, pitch them! Do it, I tell you! The can lands with a sickening kerplunk. I'm left with two cabbage stems and wet, fermented raisins in a plastic bag. The stems are slimy and bitter. I eat them anyway.

A smaller variety of fish has appeared. About twelve inches long, they have tiny, tight round mouths and little flippers like hands waving on the top and bottom of their bodies. Their big round eyes roll as they dart under the raft and peck at the bottom with their strong jaws. Are they trying to eat it? They must be the tough-skinned triggerfish. Reef triggers eat corals and are considered poisonous, but survivors have often eaten triggers from the open ocean with no ill effects. Anything would be good to eat, anything to stop the gnawing in my gut. I may soon go mad, eat paper, drink the sea.

Often when I have gone offshore, I have found myself to be somewhat schizophrenic, though not dysfunctional. I see myself divide into three basic parts; physical, emotional, and rational. It's common for solo sailors to talk to themselves, to ask for a second opinion about how to deal with a problem. You try to think as another person, to get a new outlook and to talk yourself into positive action. When I am in danger or injured, my emotional self feels fear and my physical self feels pain. I instinctively rely on my rational self to take command over the fear and pain. This tendency is increasing as my voyage lengthens. The lines that stretch between my commanding rational self and my frightened emotional and vulnerable physical selves is getting tighter and tighter. My rational commander relies on hope, dreams, and cynical jokes to relieve the tension in the rest of me.

In my log I write: "The dorados remain, beautiful, alluring. I ask one to marry me. But her parents will not hear of it. I am not colorful enough. Imagine, bigotry even here! However, they also point out that I do not have a very bright future. It is a reasonable objection."

Watching the fish makes my stomach ache more. I continue to fail at fishing. I manage to spear a triggerfish but it jerks free. I make a lure by tying together hooks, white nylon webbing, and aluminum foil, then stuffing it with a precious morsel of corned beef. A dorado strikes hard and bites effortlessly through the heavy codline. This fish is now easy to recognize, with the long line trailing from his mouth. I have no wire leader to catch these fish by hook and line so I must rely on the spear.

Finally my aim is true. The spear strikes home. A dorado erupts with resistance and thrashes wildly. I fumble for the spear, try to keep the tip away from the raft, and haul the fish aboard. Just as I get it to the edge, a final convulsion turns fury to escape. Perhaps I can live twenty more days without food.

If hunger is the witch, thirst is her curse. It is nagging, screaming thirst that causes me to watch each minute pass, to wait for the next sip. I've had only one cup of water for each of the first nine days. Daytime temperatures are in the eighties or nineties. Hours pass between single swallows of water. To keep cool and reduce sweating, I pour seawater over myself. Dry wind bites my lips. A light rain fell one evening, but its mist quickly dried. The winds here have come from America in a long and roundabout route. They first travel north and east until they reach Europe. Then they sweep south, depositing rain along the way. By the time they have reached this latitude, they are headed back west and have had most of the moisture wrung out of them. Some of the air is as dry as the Sahara over which it has recently passed. Rainfall will be rare until the winds cross enough sea to be fed by its evaporation, which will be well to the west of where I am now.

The second solar still deflates after being torn by the waves. It had never worked properly. What is wrong with them? I begin thinking of an onboard stillâthe Tupperware box, with cans inside. If I can get water to evaporate from the cans, water vapor might collect on a tentlike cover and drip down into the box. To draw more heat and increase evaporative surface area in the cans, I decide to fill them with crumpled black cloth from one of the solar stills. If I take a still apart, I may be able to find out what the problem is. I'll lose a still, but they are no good as they are. So I cut one up. I find that salt water contamination is coming from the black cloth's hitting the plastic balloon's sides when the still is not fully inflated. Excessive shaking in rough seas may also be spraying salt water from the black cloth wick into the distilled fresh water. So it is not a single problem; it requires multiple solutions. I must find and plug any holes in the balloons and stabilize the stills.