Adrift (21 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

Adrenalin begins to surge through my veins. Like magic, I get the strength to bundle up and try to regain my lost body heat. I eat whatever fish is in sight, wait, and plan. I lie awake all night planning. Every detail is considered, every contingency followed to its possible conclusion. I don't know if I'll last the night, but there is nothing to do but try. I huddle up, try to stay away from cold spots in the raft, places that have not been warmed by my body. At last my eyes can tell gray from black, and then orange from gray.

I throw off my covers and feel the cold morning breeze on my skin. With my sheath knife, I carefully cut a slit through the top lip, foam tongue, and bottom lip of the tear. I break the tines off of the fork and slip the handle through the slit so that it sticks out of both sides like a bone through a cannibal's nose. Conveniently, there are two holes in the handle, just to the top and bottom of the lips. I can lash across the patch and through the holes to keep the handle snugly in position. The line that I wind behind the handle cannot be forced off unless the handle breaks. First I use a light line to grab the middle of the lips and pinch them tight onto the tongue. Then I coil the thicker line around until it winds the lips back into a pucker and ultimately encloses the outside edges of the mouth. I know this thicker line is riot effective in making the patch airtight. Its only purpose is to lie smoothly next to itself and pucker the lips. For the final seal, I loop a tourniquet behind the coil of thicker rope and wring it tight. The thicker rope will keep the tourniquet from rolling off the edges of the mouth when the tube is inflated.

I must rest between each step of the operation, so it takes until midafternoon. When it is finished, I begin pumping up the tube, taking a half hour to do what would normally take five minutes. After an hour and a half, the reinflated tube is quite soft again. I'm depressed, but as long as I have strength I must try to make it work. There is no other answer.

The fork handle has kept the lashings on the top and bottom of the lips, but the two edges to the sides have bulged out just enough that a trickle of air escapes. I pull the lines back down over the sides, using warping lines, attachment points on the top tube, and whatever else I can think of. I give the tourniquet a few more cranks and add a second one. Time to give it another go. By now I whine more than the pump. In the hour that follows,

Ducky

gorges on air, picks herself out of the water, and drifts forward again like a lily pad cut free from its roots. I collapse into a heap of human rubble.

Twelve glorious hours pass before

Ducky

needs another feeding. Her lips have ceased to regurgitate the three hundred mouthfuls of air every few hours. I pump in only thirty little bites and her belly is as plump as a melon again. The gray sky and tormented sea continue to cast a pall over my surroundings. My body hungers, thirsts, and is in constant pain. But I feel great! I have finally succeeded!

The night I lost

Solo

and again last evening, there seemed no escape from death: it could come at any moment. The first time, over a week passed before I became accustomed to the raft and saw that there was a possibility that I might get enough food and water to crawl out of this hell hole. This time it was much worse. After the bottom tube was punctured, my life in the raft was more horrible than I could have imagined early in the voyage. I feel as though I have been twice to hell and back, and each successive journey has taken longer, been more hopeless and abominable. I will never last another one. Even now I wonder if I will be able to recover enough strength to last three or more weeks, long enough to reach the islands. I must be positive about it. I must regain a firm and unquestioned command of my ship and myself, for there is a great deal I must do. I get up, face the wind, and in no uncertain terms tell the Grim Reaper to get lost!

E

VOLUTION OF THE PATCH IN THE BOTTOM TUBE.

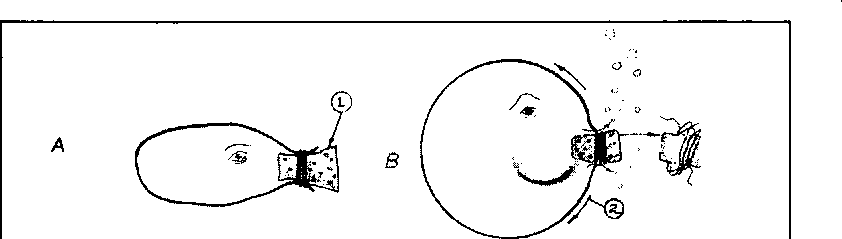

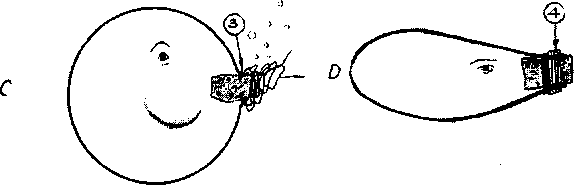

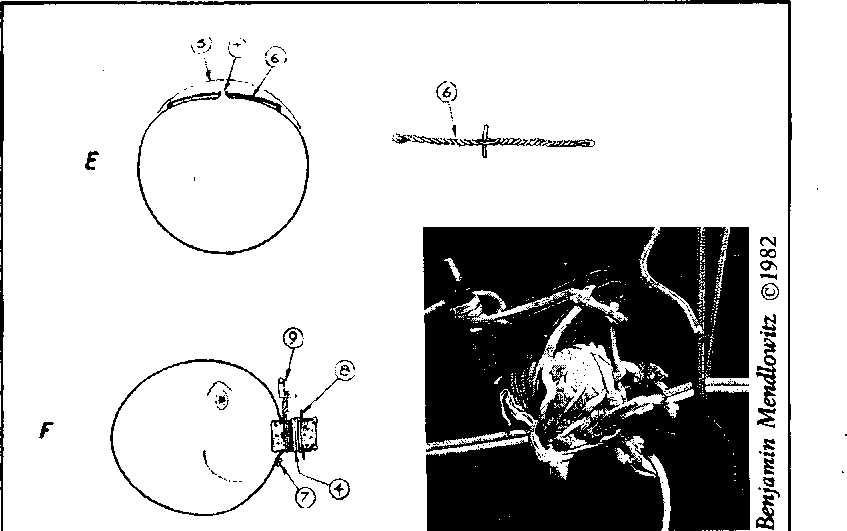

(A)Â The tear is like a mouth. I push a foam plug (i) into the mouth and wind lashings around the lips. From a top view the edges of the mouth would be barely enclosed by the lashings. (B)Â When the tube is inflated, it pulls the lips apart (2). They work out from under the lashings, the lashings and foam plug fall out, and the tube again deflates. (C) Holes are punched through the lips and plug and it is "sewn" into place (3). However, when the tube is inflated, the lips are again pulled apart and the small diameter line rolls over itself and again falls off. (D) I wind a larger diameter line around the lips (4). This keeps the smaller line inboard of it. However, when the tube is inflated, the same problem occurs. The lips are pulled apart and both the large and small diameter lines are forced off of the plug. I use extra line to tie the large diameter line to various tie-down points on the raft. However, they are not numerous enough or close enough to the patch to be totally effective. They keep the lines from completely falling off but the edges of the liDS still Dull out from under the lashings no matter how tightly they are wound around the mouth. (E) The normal raft shape as viewed from above and how I warp it in order to gather more of the lips around the plug. Dotted line (5) shows the rafts normal, circular shape. By using a loop of line, twisted in Spanish windlass style (6)Â , two anchor points on the raft are pulled together. This allows the mouth to be slightly puckered even when the raft is reinflated (7)Â . (F) The final, primary patching system. (External pressure patches and lines tying the various lines to anchor points on the raft are also necessary to make the patch effective but are not shown here, for clarity.) A fork handle (8) is inserted down through the top lip, plug, and bottom lip. This keeps the lashings from being forced off the end of the patch. The large line (4) is wound around until all edges of the mouth are caught. Then small diameter line is wound tightly around in order to apply pressure on the lips against the due Finally a tourniquet (9) is used to maximize pressure on the plug. This keeps the edges of the mouth that "are perpendicular to the fork handle from pulling out from under the lashings and it cinches the patch so tightly that it finally holds air better than the undamaged top tube. PHOTOGRAPH OF THE FINAL PATCH. Tie-downs to a nearby anchor point and to the warping Spanish windlass (7) can be seen running under the patch. The metal pintle serves to tighten the tourniquet and is also lashed into place.

I have no more fish and little water. Night falls and the sea batters me painfully, but I cannot stay conscious. I rest, find sleep, await the sun's return, and ever so slowly return to the land of the living.

On our fifty-third day, the sun brushes the clouds aside while the wind pushes us onward. The patch has loosened slightly but has held. I feel as if I've been run over by a locomotive, but I have more confidence than ever that I will make it. Even if the patch fails, I can make a replacement rapidly. The system works. My position is still about three weeks away from the islands. My body has reached a new low, has no chance to recover and no hope of coping with another major disaster. From here on it will be a full-time struggle to hang on to but not break the thread that connects me to my world.

At the beginning of my voyage, there was little distinction between my rational mind and the rest of me. My emotions were ruled by nearly instinctive training and my body did not complain about having to work. But the distinction between the parts of myself continues to grow sharper as the two-edged sword of existence cuts one or another of them more deeply each day. My emotions have been stressed to the point of breaking. The smallest things set me into a rage or a deep depression, or fill me with overwhelming compassion, especially for my fish. My body is now so beaten that it has trouble following my mind's commands. It wants only to rest and find relief from the pain. But rationally I have chosen not to use my first aid kit because it is small and I may need it more later if I am severely injured. Each decision like this by my mind comes at an increasing cost to the rest of my crew. I must coerce my emotions to kill in order to feed my body. I must coerce my arms and legs to perform in order to give myself a feeling of hope. I try to comply with contradictory demands, but I know the other parts of me have bent to my cold, hard rationalism as best they can. I am slowly losing the ability to command, and if it goes, I am lost. It becomes a problem that surpasses the constant apprehension of living on the edge. I carefully watch for signs of mutiny within myself.

For the first time, I try to dry out my sleeping bag by draping it over the canopy of the raft. Heavy with water, it crushes the canopy. I pump up the arch tube as tightly as possible. It's all my rubbery legs can do to support me for the minutes it takes to maneuver the bag and tie it down to keep it from flying away. The inside of my cave is now dimmer and cooler, an advantage as the sun reaches its zenith. Despite occasional spray rewetting the bag, by nightfall it is mostly dry. Each evening, though, dampness from the air is drawn into the salt-encrusted seams.

The still is not functioning properly. The cloth wick is not getting as wet as it should. Evidently the valve is plugged. A jiggle string passes through the valve to regulate flow. It's stuck, and after some tight maneuvers I manage to free it with the tweezers from the first aid kit. Time and time again the jiggle string becomes relodged. I lash my only safety pin onto a pencil and bend the point out straight. I must be very careful not to puncture the balloon. I maneuver the prong down through the valve to free it. This still deflates each night. At dawn I inflate it, empty it of salt water, and prime it up. All day I nurse it, feed it salt water, operate on the valve seizures, and maintain the perfect level of inflation. I must doctor the still constantly, and in return the still nurses my feeble form with fresh liquid.

The sun climbs up to its throne. Beads of silver slowly grow on the inside of the balloon and eventually they drop down, leaving black streaks as they roll along the inside of the balloon's surface, collecting the silver condensation as they go. My eyes are heavy. The monotonous progression of waves drones a chant of rolling lullabies, and the slow drip, drip, drip ... My eyes open with a start. How long have I slept? Half hour, maybe. The still, too, has slumped over. I grab the collection bag. Much too full. Damn! Contaminated with seawater again. Chalk off another six ounces of good water. From now on I'll empty the bag every hour or more. The forced activity will help to keep me from lapsing into sleep. Two tropic birds flap by in their awkward way, hiding behind their black masks and laughing at me. I don't find it very funny. I prop the still back up and get it to sweat. Gnawing on a triggerfish fillet, I discover that they don't taste so bad if dried a little.

Yesterday I began the hunt again. The doggies seemed to know I was back in the game. As my point neared the water surface, their groups burst apart and scattered. I couldn't hold my hunting position for long, but the triggers underestimated me. They must have thought that I'd have packed it in by sunset. I ground my teeth in the shadows and stabbed one, then another. Two clicking bodies lay before me. I ripped into the first like a werewolf, and after licking the remaining strands of flesh and guts off of my beard I felt much revived. The second I stretched out on my board and dissected under the beam of my flashlight, which I held in my mouth. I tossed the flesh into the Tupperware box and fell asleep. I woke toward midnight and found an eerie aura casting shadows. The Tupperware box was glowing. I drew back the top and saw the dead meat alive with light. Phosphorescent plankton, which lodge in the weeds and barnacles on which the trigger feeds, must have found their way into the fish's flesh. The light from their microscopic lives illuminates my world long after they have died.