Adrift (19 page)

Authors: Steven Callahan

Yesterday the leak worsened. I tried to increase outside pressure by securing another retaining line across the patch, but it pulled the plug a little to the side and the serpent's silvery tongue of bubbles lashed out. After several hours of adjustment, I got it caged again, but an evil hiss of air escapes nonstop.

There is often water in the raft these days. My legs push the rubber floor into the sea until I'm about mid-thigh deep, and the water forces the rubber to hug my legs. I feel like I'm wearing flooded hip boots. When I want to move, I have to yank one leg out at a time, struggle to pull it up high enough to clear the bulging bottom, and sink it down again a little closer to my destination, all the while balancing on one leg. When I lose my balance, I fall into the black, clutchy amoeboid, and it's quite a battle to keep from being totally engulfed. It's worse in the middle, of course, so I try to keep to the edges of the raft. Even so, the clinging rubber pulls the heads off of the hundreds of boils that have erupted on my legs and back. Some of the salt water sores are wedged tightly in my crotch and others dot my chest. My body is rotting before my eyes.

I ignore the pain and try to fish. Through my feverish, dizzy vision, I see that I've managed to board two triggers. I have also struck two dorados, but each time the thin knife I'm now using for a spear point simply bent over. Even when I hit dorados hard enough to cut into the flesh, they easily wiggle away. With the blade bending this way and that, I expect it to snap off at any time.

In my bag I find the leather knife with which I cut

Ducky

free from

Solos

deck a month and a half ago. I break off the wooden handle, remove the stiff steel blade, and hone it on my stone. I lash the butter knife to one side of the spear shaft and the leather blade to the other, and match up the tips to form a V-shaped arrowhead. Through the holes in their handles, I lash the knives around the spear shaft and to each other. If I have enough strength, the spear will hit the dorado like a meteorite and leave a gaping crater. To increase the point's holding power, I bend the butter-knife handle out from the shaft to act as a barb. These blades are the last pieces of metal I have from which to manufacture a spear point. Losing them may cost me my life. A retaining line from the butter knife to the handle of the gun is my life insurance; I tie the gun to the raft with lanyard as well, and keep it ready on the spray skirt, which lies across the raft's threshold. I make a sheath for the tip so that

Ducky's

tubes will be safe even when the spear is picked up and thrown by the hands of the Atlantic.

E

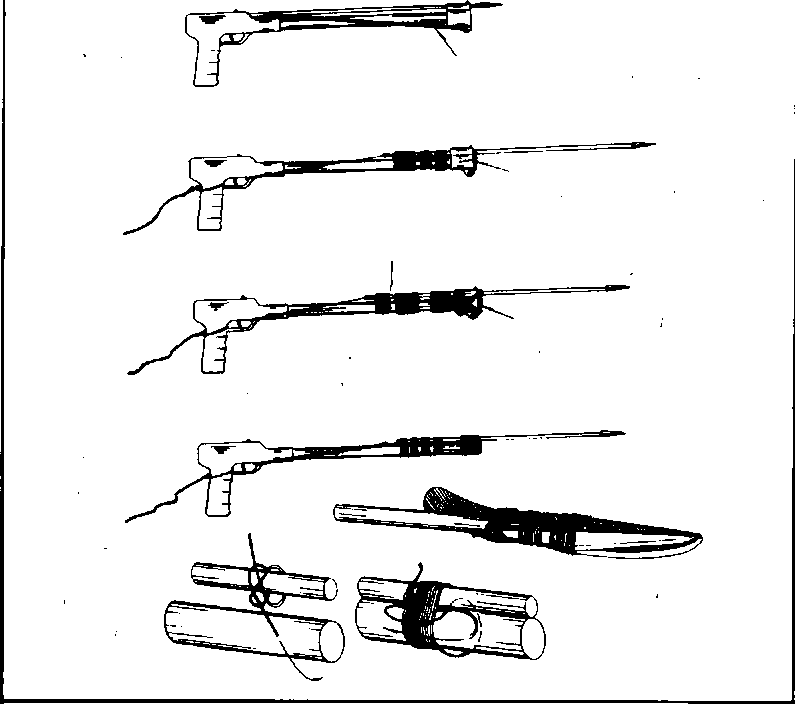

VOLUTION OF THE SPEAR

, profile views: In the first view, the arrow indicates the elastic power strap that propelled the spear arrow before it was lost. In the second view, I pull the arrow out to maximize the weapon's range, then lash the arrow tightly to the gun shaft. A retaining line from the notch in the butt of the arrow back to the trigger guard assures that the arrow cannot be pulled out forward. The spear arrow still rests through the plastic housing/guide at the tip of the gun. Battles with the dorados put large side loads on the arrow and gun, which is not the normal direction of load for a spear gun. The side loads soon put a crack in the plastic housing, indicated by the drawn arrow. In the third view, I attempt to reduce this side movement by pulling the arrow further back onto the gun handle. I also reinforce the plastic tip with additional lashings. However, the next dorado's strength bursts the plastic tip apart, causing the arrow to twist to the side and snap off where indicated by the drawn arrow. Now the fish pulls the arrow out of the aft and middle lashings, leaving only one to hold it onto the gun handle. It twists the arrow around, and rams it into the bottom tube of the raft. In the

bottom profile view,

I lash the arrow directly onto the gun shaft. The retaining line now runs from the foremost lashing back to the trigger guard, so that the lashing cannot be pulled off the end of the gun shaft.

I

MPROVISING A NEW SPEAR TIP

: Finally a dorado unscrews the barbed point of the spear and steals it away. On one side of the shaft I put a stainless steel butter knife. On the other, closer to the viewer, is the blade from a leather knife. Each has holes in the handle ends, so I tie them tightly together, and then wrap them securely with lashings. I bend the handle of the butter knife away from the arrow shaft in order to serve as a barb. Through the hole shown in the handle I attach another retaining line and lead it aft. Even if the knives are pulled off of the end of the arrow shaft, they will still be attached to the raft. To increase penetrating power and to allow the blades to support one another against heavy side loads, I bend the blades so that the tips touch, creating a large V-shaped blade. The foremost lashing extends forward of the arrow shaft so that it helps to keep the blade tips pulled together.

The bottom sketches show the procedure for making a lashing of this type, which is very useful to sailors.

Left:

Tie a clove hitch around one shaft. If you tie it around both, it will twist around them, following your lashing windings, and the lashing will quickly loosen.

Right:

Wind the line around neatly and tightly. Bring the end of the rope up

between

the two shafts, then thread the line through the small gap between the shafts, perpendicular to the windings. These trappings pull the windings very tight and also keep them from wandering. Three or four of these trappings are enough. Finally finish off with another clove hitch, preferably on the shaft and side opposite from which you began. The clove hitch shown is composed of only two turns around the shaft. However, additional turns can create a multiple clove hitch. I usually prefer about four, essentially one clove hitch next to the other This way should one turn work loose the essential hitch next to the lashing will remain tight.

Before I have time to test the new spear tip, the plug in the bottom tube trembles and little geysers shoot up at the bow. I put another tourniquet around the pads and plugs and twist it tight. A volcano of fat bubbles spews forth. She's blown again.

The still is also leaking more as my old repair works loose. I can't stop to reinflate the still when I am in the middle of lashing up the raft patch, so it slumps before I can get to it. The distillate becomes tainted with salt water. Just how tainted is hard to tell. I decide it is not

too

salty to drink, but as the salt level in my body builds, my ability to taste salt decreases. The fact that seawater is beginning to taste pretty fresh is frightening.

It is dusk when the patch blows, so I lie awake through the night with the tube deflated, huddling as close to the outside of

Ducky

as possible to keep from sagging too deeply into the floor. Cold and wet, I feel as if I'm lying in a hammock full of water, turned on its side. A heavy, rough lump brushes against me. Another shark. I grab my spear and try to maneuver for a shot. The squealing rubber floor sucks up my legs, twists, and tries to tear off my skin. I cannot see the shark, so try to pull my leggy lures out of the sea by sitting half up on the inflated tube with my head crammed against the canopy. Shivering, I await the dawn.

In every dusty corner of the attic of my mind, I search for a way to patch the leaking tube once and for all. The smaller line that I've been using for lashing rolls over itself too easily, until it rolls right off the end of the tear's puckered lips. Maybe if I use bigger line, it won't be able to roll over itself. I will grab just the tip of the puckered lips and wind the line so that the coils lie smoothly next to one another, spiraling like wire wound around a drum, pulling more and more of the lips under its control until the whole mouth of the tear is enclosed.

At daybreak I try this with quarter-inch line from the sea anchor. Thank God, it works.

Three hours later the whole thing blows.

I retie it, add some small-line tourniquets inboard of the large-line windings, and replace the external pressure-retaining lines. I pump up the tube until it is just hard enough to hold its shape.

Something beats monotonously at the floor. I sprawl across the top of

Ducky's

canopy, crushing it down, and peer over the stern. I can feel that the rusty gas cylinder, which originally blew the raft up, has fallen out of its pouch. Not only is it good shark bait but its coarse metal may quickly scrape another hole in my ship. The wind has risen and waves slop over me as

Ducky

lifts and plunges like a pump diaphragm. I pull up on the gas line that connects the bottle to Duck's bottom tube. The gas bottle is heavy, full of water, I suppose, and refuses to be reseated. The gas line has been pulled through the bottle's pocket so there's not enough slack to pull it up and out of the water. Can't get it back in and can't get it out, and I certainly can't leave it as is. Damn! I feel for the pocket and begin to slash away at it with my sheath knife, being very careful not to drop the blade or ram it into the tube. Twice a sharp pain runs up my arm. No matter. It's okay if I cut myself. Finally it's done, and I pull up the bottle and tie it to the upper tube.

My arms feel like lead, my whole body aches, and my head feels as if it's been stuffed. For the past several days, I've had only a few hours' sleep and I've been sitting in salt water continually. Boils have burst open. Ulcers are growing. The hole that I rubbed through the skin of my left forearm while working on the patch has expanded, grown foul and smelly. I desperately need to satisfy the contradictory demands of food, water, and sleepâfish, navigate, tend the still, and keep watch until I drop. I get another trigger and devour the sour animal as if it were roast duck. The need to reinflate the raft again and again robs me of my sleep at night. There is no longer a clear line between good and evil, beauty and gruesomeness. Life is only one blurry moment following another deeper into fatigue and pain. I have become so conditioned to go through the motions of survival that I do them without thinking. It rains, and I leap to collect about six ounces of water, watching in disgust as small rivers pour into the mouth of the canopy, pure water turning instantly to bile.

The weather has been calm since the bottom tube was damaged. On the one hand, this has been fortunate because it has allowed me the time to evolve a patch. If a storm had hit when the bottom tube was deflated, I probably would have drowned, and almost certainly my equipment would have been torn out and washed away. As always, what's good on the one hand is bad on the other. In this period of calm, progress has been dreadfully slow. Recently the breeze has builtânow to about twenty knotsâand things are rough but not stormy. I'm glad the weather is back. At least we are moving again.

I have been too weak to do yoga for over a week. Before the accident, I thought I had reached a sort of starved, steady state, but now my body is becoming more battered and even thinner. I can take it. Others have taken worse. You're on the home stretch now, no letting up, push the pace. You've got to move even if you punch more holes in your hide, got to drive on. No second place in this race, only winning and losing. And we're not talking ribbons or trophies, here. You've got to hang in and be tough.

Will the seas punch the patch apart? Now, don't panic. DO NOT PANIC! Somehow I sleep. I dream that all of my family, friends, and those I've loved are gathered for a picnic. I try to take a picture of them sitting on a stone wall. Can't fit them all in. "You've got to get back," they shout to me. "Back, back, farther, keep going farther." I move back more and still more, bringing crowds into the frame. Thousands of speckles shout, "Back farther!" They shrink more, and still more sweep into view, until everyone turns to a blur and is gone.

The soggy floor of the raft is in such unbelievable motion it feels like a carnival ride. I can't imagine trying to effect another repair in these conditions. The patch splutters and spews, but it holds.

To protect the bow of the raft from my spear should another spear failure occur, and to prevent curious fish from nipping at the patch, I drape a bib of sailcloth through the entrance over the bow and let it drag under the raft.

Rubber Ducky III

has become a big-mouthed sea creature with a haggard tongue hanging out. I dangle inside like a weak tonsil. I pull the tongue tight against the raft so it does not flop, which would reduce my visibility and range for fishing.

Ducky

and I are now ready to gobble up anything in our path.

The farther west we get, the more we feel the effects of the warm, moist easterly trade winds. Cauliflower cumulus begin to sprout from the fertilized sky. Small showers fall in gray smudged streaks. I remove the kite that I'd originally made as a signaling device but ended up using to catch water that comes through the leaky observation port. I replace it with a plastic bag, which serves the purpose temporarily but not very efficiently. As the rain comes down, I hold the kite up like a shield against the drops, with the point down in the Tupperware box. The added square footage allows me to catch almost a pint of the sky's elixir.