1912 (5 page)

Authors: Chris Turney

The largely Scandinavian team took with them three British and Australian scientists, and returned to Cape Adare in northern Victoria Land, the site of Borchgrevink's first steps. Relations between the Norwegian and the rest of the men became so bad that at one point the leader produced a notice which declared, âthe following things would be considered mutiny: to oppose C.E.B. [Borchgrevink] or induce others to do so, to speak ill of C.E.B., to ridicule Mr. C.E.B. or his work, to try and force C.E.B. to alter contracts.' Somehow they soldiered on, and in 1899 the expedition became the first to winter on the Antarctic continent. At the end the Australian Louis Bernacchiâin charge of magnetic measurementsâsaid, âWe are not sorry to leave this gelid, desolate spot, our place of abode for so many dreary months!'

The following summer they sailed on towards the Great Ice Barrier and reached what the papers described as âFurthest South with sledge â record â 78 deg. 58 min.' It had been some time since anyone had spoken publicly of trying for the South Geographic Pole. The race was on, if you were in search of fame and perhaps fortune.

The British were not overly concerned with the geographic pole, although there was no doubting this was a good way of raising public interest. The official aim was to discover more about this new land in the south, not merely to reach what many felt was an arbitrary spot on the ground. By lobbying and cajoling

where necessary, Markham and Murray managed to secure enough funds from private benefactors and the government of the day to get an officially sanctioned British expedition. Most of the money came from the industrialist Llewellyn Longstaff, who offered £25,000, with the government offering a further £45,000. Britain's National Antarctic Expedition was born.

Markham had for some years maintained a list of young naval officers with the potential to lead the new initiative. The Royal Navy had led polar exploration since the end of the Napoleonic Wars: young officers, it was believed, could be explorers and serve science at the same time. As Admiral Sir Richard Hamilton, another veteran of the search for Franklin, remarked in 1906: âIt was the belief of all of us, then the rising generation of 1850, that polar exploration was essentially the work of young men in full possession of their physical powers, with, of course, a fair amount of knowledge of various sciencesâ¦The most experienced whaling captain cannot foresee the rapid changes in ice-movements. So inexperience is not as heavily handicapped in the ice as elsewhere. The power of instant decision is what is required.'

In 1899, two days after advertising for a leader of the National Antarctic Expedition, Markham ran into Robert Falcon Scott, a 31-year-old torpedo officer on leave in London. Encouraged by Markham, Scott applied for the position and was appointed leaderâhis enthusiasm trumping his polar inexperience.

The National Antarctic Expedition began to take shape. But the alliance between the Royal Geographic Society and the Royal Society, its co-sponsors, was not an easy one. The RGS wished to concentrate on geographical discovery, while the Royal Society wanted to put more resources into scientific observation. Sir Clements Markham considered dedicated scientists undesirable camp followers, âmud larkers' who impeded the business of discovery by pottering in the field.

The Royal Society had considered Scott to be the leader of the expedition for the journey to Antarctica, and envisaged a trained scientist being the leader on the ice. After all, this was a scientific expeditionâor so the Royal Society thought. Professor John Walter Gregory was appointed scientific director. A geologist, he had worked from the tropics to the Arctic and achieved fame as an explorer, naming Africa's Great Rift Valley during one of his sojourns. In anticipation of the rich scientific rewards to be had in the south, Gregory made a call for research ideas in the journal

Nature

. Unfortunately, the two men were not natural teammates. Gregory complained that Scott had âno knowledge of expedition equipmentâ¦On questions of furs, sledges, ski etc, his ignorance is appallingâ¦he does not seem at all conscious of these facts or inclined to get [the] experience necessary.' Scott seemed likely to resign over who was in charge. Markham weighed in, and instead the Royal Society's candidate fell on his sword. With Gregory gone, Scott was now in sole charge of what threatened to become a ânaval adventure'. The relationship between science and exploration had not got off to a good start.

Nonetheless, Scott tried to recruit as much scientific expertise as possible. One of those he attempted to take south was a rising star in polar research, the Scot William Speirs Bruce. Full of scientific and nationalist zeal, he had experience of polar waters in both hemispheres. Keen to take his own group south, Bruce turned down Scott's approach. Instead, he raised private funds, controversially named his effort the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition and set off in his ship, the

Scotia

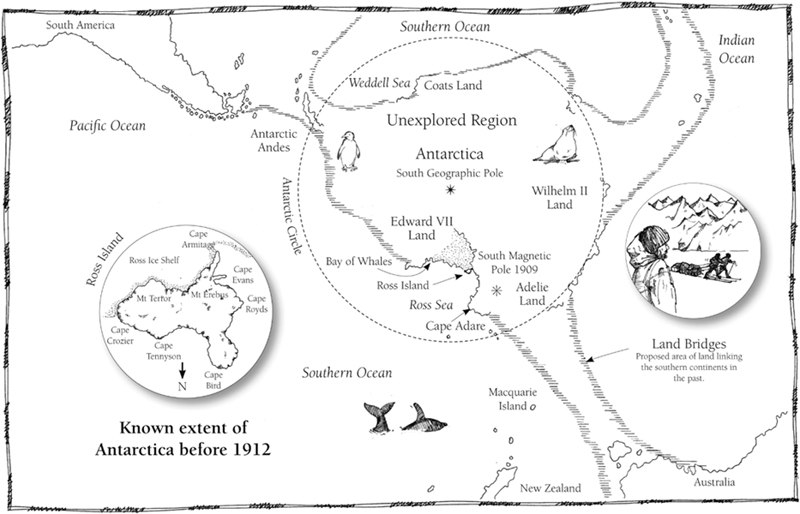

, in 1902. Two years later Bruce returned home a hero, and described exploring the seas and weather of the Weddell Sea, including discovering a new coastline he called Coats Land after one of his major sponsors. Finding the pack ice too thick, he could not penetrate as far south as Weddell, and vowed to go back.

Markham described the Scottish effort as âmischievous rivalry', and never forgave Bruce for it.

Meanwhile, Markham had organised the publication of

The Antarctic Manual

before the official British expedition headed south. Meant as a guide for naval officers and scientists, the

Manual

described the history, scientific questions and methods required in the south. It provides a fascinating insight into what was known of the Antarctic at the beginning of the twentieth century: expedition members were to research the ice within glaciers, investigate the saltiness of seawater and acquire skill in âski running'; they were advised which geological samples they should bring home, and that âa sandwich of frozen bear's blubber and biscuit is palatable enough.'

Magnetic observations were a focus of investigation. Although some had been taken on Borchgrevink's expedition, the location of the South Magnetic Pole remained uncertain, making it difficult to verify calculations of the Earth's magnetic field. To try to avoid the problems Ross had complained of more than half a century before, a specially designed wooden ship capable of making precise magnetic measurements was made. Called the

Discovery,

this vessel was Britain's first purpose-built craft for scientific work since Halley's

Paramore

. Lieutenant Albert Armitage, the expedition's deputy and in charge of the observations at sea, complained about the storage of tinned provisions immediately below the instruments, alongside âunconsidered trifles such as a parrot-cage, a sporting-gun, and various assortments of enamelled ironware', forcing the vessel to be swung just as Ross had done with his ship to ensure accurate readings. But at least it was designed like a Scottish whaling vessel, providing a heavily reinforced oak hull that made short work of the Ross Sea ice.

By the time the

Discovery

left Britain, in 1901, £92,000 had been raised, the largest sum yet collected for a polar

expedition. Establishing a base on the McMurdo Sound side of Ross Island, Scott's team spent the next two years exploring the region. Even today, though, the expedition's success is fiercely debated.

Undoubtedly, there were some tangible results. Exploration by the

Discovery

gave an eastern limit to Ross's Great Ice Barrier with the finding of ârock patches', which were christened King Edward VII Land. On the barrier itself, the expedition located the bay Ross had described as full of whales and flew a hydrogen balloon above it, taking the first aerial photograph of this new continent over what became known as Balloon Bight. Magnetic measurements were made both on shore and at sea, providing a revised estimate of the location of the South Magnetic Pole, which implied it had moved in an easterly direction since Ross's 1841 visit. A party made the first successful ascent of the mountains of Victoria Land and reached a plateau of ice, some three thousand metres high, which suggested that both the geographic and magnetic poles lay at a considerable altitude. Continuous weather observations, painstakingly taken several times each day, showed the climate was like nowhere else on Earth, with temperatures plummeting at the end of summer to around -30° Celsius and staying there until the start of the following summer. On the other side of Ross Island, at a spot called Cape Crozier, the first colony of emperor penguins was discovered, and to much amazement were found to have well-developed chicks in early summer, indicating they had hatched during the harsh winter. A unique land was finally being revealed to the rest of the world.

Much like the Belgian effort, though, the British had their share of controversy. The expedition suffered for a time from scurvy. And while attempting to reach the South Geographic Pole, Scott, the assistant surgeon Dr Edward Wilson and third lieutenant Ernest Shackleton only reached a disappointing

furthest south of 82°11'S, among much later-reported acrimony. Most importantly for the British authorities, the

Discovery

was locked in sea ice for two years, rather than the publicly declared plan of one. There was a justifiable fear of escalating costs. By the end of the second season the authorities' patience snapped and they sent two vessels south to recover the men, with orders to abandon the

Discovery

if it could not be released. At the last moment the expedition ship escaped its icy grip, helped by the judicious application of explosives.

And yet,

Terra Australis Incognita

had been shown to be real and Captain Cook's earlier pessimism unfounded. The National Antarctic Expedition returned home to much fanfare and, notwithstanding some mutterings of discontent, Scott was proclaimed a hero. But there was no rush of expeditions south to build on the British work. To understand why, we have to turn our attention to a member of Scott's team: one of the most inspirational explorers of all time, Ernest Shackleton.

Hypothesised former land bridges from A. E. Ortmann's Tertiary Invertebrates (1902).

AN AUDACIOUS PLAN

Ernest Shackleton and the British Antarctic Expedition, 1907â1909

Â

Yes, they're wanting me, they're haunting me, the awful lonely places; They're whining and they're whimpering as if each had a soul; They're calling from the wilderness, the vast and God-like spaces, The stark and sullen solitudes that sentinel the Pole.

R

OBERT

W. S

ERVICE

(1874â1958)

In January 1904 a prematurely old-looking middle-aged professor of geology stood up in a packed hall in the New Zealand city of Dunedin and gave one of the most controversial but least reported lectures in the region's history. The Welsh-born Edgeworth David, known affectionately as the Prof, was president of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science. David believed science was pitted against a significant foe, one that threatened the antipodean colonies' ability to contribute to the British Empire. To the assembled he calmly proclaimed: âIt should, I think, be one of the aims of this Association to discover and destroy the microbe of sporting mania.'

Not only was sport directing effort away from the advancement of scientific knowledge, he arguedâit was also threatening the quality of education. âWhen we worship in the cricket or football fields the wood and the leather,' he said, âwe must remember that they are but idols, and must not let them occupy the chief

shrine in our hearts.' Science was suffering. Antarctic exploration promised some answers, but âgeography', he declared, âlike charity, should begin at home: the real scientific geography of the interior of Australia is at present almost unknown'. Shortly afterwards, a flamboyant Anglo-Irishman changed the Prof's mind about the value of scientific work in the south.

The early Antarctic incursions of de Gerlache, Borchgrevink and Scott had set the scene for the greatest schoolboy hero of them all, the most charismatic of Antarctic leaders, Ernest Shackleton. Born in 1874 in County Kildare, Shackleton moved with his family to London when he was ten years old. Though keen for Ernest to pursue a career at sea, the family could not afford the price of a commission in the Royal Navy. Instead, Shackleton signed up for the mercantile navy and eventually joined the Union-Castle Line operating between Southampton and Cape Town, ferrying passengers, mail and, later, troops for the Boer War. During one of the crossings he met a young army officer whose father, Llewellyn Longstaff, was one of the primary backers of Scott's

Discovery

expedition. With the bold confidence and good fortune that would define his career, Shackleton introduced himself to Longstaff senior when next he was in London. The old man was impressed and insisted Scott take the young officer south in 1901.