1912

Authors: Chris Turney

1912

Professor Chris Turney is an Australian and British Earth scientist, and an ARC Laureate Fellow in climate change at the University of New South Wales. He is the author of

Ice, Mud and Blood: Lessons from Climates Past

and

Bones, Rocks and Stars: The Science of When Things Happened

, as well as numerous scientific papers and magazine articles. In 2007 he was awarded the Sir Nicholas Shackleton Medal for outstanding young Quaternary scientists, and in 2009 he received the Geological Society of London's Bigsby Medal for services to geology.

COUNTERPOINT

BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA

Â

Copyright © Chris Turney 2012

Maps copyright © Elaine Nipper 2012

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

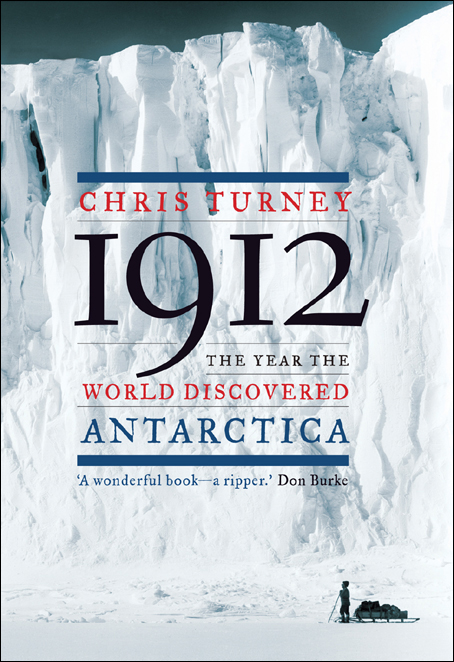

Photo of British expedition member and dog driver Anton Omelchenko below the Barne Glacier (Mount Erebus, Ross Island), December 1911, by Herbert Ponting, courtesy of the Scott Polar Research Institute (P2005/5/647); photo of king penguin, South Georgia, 2011, by Chris Turney; photo of Chris Turney in 1912 explorer gear © John Murray / Crossing the Line Films

Cover design by WH Chong. Text design by WH Chong & Imogen Stubbs. Typeset by J&M Typesetting.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-61902-137-2

COUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

Distributed by Publishers Group West

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To my grandparents Jim and Bunty,

whose hard work and tales of

adventure continue to inspire me

Ernest Shackleton and the British Antarctic Expedition, 1907â1909

Robert Scott and the

Terra Nova

Expedition, 1910â1913

CHAPTER 4: Of Reindeer, Ponies and Automobiles

Roald Amundsen and the Norwegian Bid for the South Pole, 1910â1912

Nobu Shirase and the Japanese South Polar Expedition, 1910â1912

Wilhelm Filchner and the Second German Antarctic Expedition, 1911â1912

CHAPTER 7: Ice-cold in Denison

Douglas Mawson and the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911â1913

CHAPTER 8: Martyrs to Gondwanaland

The Cost of Scientific Exploration

Â

People, perhaps, still exist who believe that it is of no importance to explore the unknown polar regions. This, of course, shows ignorance. It is hardly necessary to mention here of what scientific importance it is that these regions should be thoroughly explored.

F

RIDTJOF

N

ANSEN

(1861â1930)

It's early January 2011 and I'm sitting in a four-engine Iluyshin transporter plane ten thousand metres above the Southern Ocean, heading towards one of the Earth's most remote places. The cabin is packed with fifty-odd passengers, fuel, equipment and the most eclectic range of clothing I've ever seenâmulti-coloured jackets, salopettes, and gloves and hats of all shapes and sizes, in anticipation of sub-freezing temperatures. Unlike most of my fellow travellers, who are heading off for a couple of weeks of climbing, skiing or kiting over ice and snow, I'm about to fulfil a lifelong dream: to research the geological and climatic history of a remarkable part of the world.

A few hours earlier we were standing on an airstrip in the relatively balmy city of Punta Arenas, in southern Chile, threatening to break out in a sweat. Now we're hurtling along in what feels like an oversized Soviet coffin and about to land on a worryingly narrow strip of ice. The pitch of the engine suddenly

changes, and we know we're getting close. We take our seats, necks craned to see the fast-approaching mountains and snow.

A slight bounce and we're down on an ice runway at a frigid 79° South. The engines drop to a low whine and we taxi to two blue containers that mark the Union Glacier airbase, our new home. The rear cargo doors open up: brilliant light and freezing air pour into the hold. There's a collective intake of breath. We're in Antarctica, and all it took was four hours.

In 1897 an exasperated John Campbell, Duke of Argyll, declared in London, a âvery large area of the surface of our small planet is still almost unknown to us. That it should be so seems almost a reproach to our civilisation.' Atlases at the turn of the century only hinted at what lay at the end of a world populated by one and a half billion people. Almost everything south of 50° was described as an Unexplored Region and the vast space left embarrassingly empty.

The dawn of the modern age saw major advances in science, technology, engineering, social reform and politics. Nations were talking to one another with a new confidence, and the world suddenly seemed smaller. And yet, despite the progress made during the Victorian era, the uncertainty over what lay south grated. When the Edwardian world looked to the other side of the planet, it did not know what was there.

While the likes of David Livingstone, Alexander von Humboldt and John Hanning Speke had blazed a trail through Africa and the New World, reaching ever further inland and becoming household names in the process, few western explorers had ventured to the Antarctic Circle. Little was known about it, beyond hearsay: it was a region of wilderness and extremes, of rough and icy seas that took ships on a mere whim,

of wild animals in the depths. Imagination and fancy filled any disagreeable gaps in knowledge, for only a handful of adventurers had penetrated this inhospitable region and returned to tell a plausible tale. The Antarctic remained stubbornly off the map, save for a smattering of islands and disconnected coastlinesâmany of them considered highly suspectâpeppering a swathe of white.

Never has a continent been more misunderstood. Antarctica is on a scale hard to grasp: at over fourteen million square kilometres, it is second only to Russia in coverage of the Earth's surface and bigger than all the countries of Europe combined. It is the world's highest continent, with an average altitude of 2300 metres. It contains more than seventy per cent of the world's freshwater, locked up as thirty million cubic kilometres of snow and iceâwhich, if melted, would raise the planet's seas by an estimated sixty-five metres, easily flooding the likes of Sydney, London and New York. The bitterly cold air on its upper surface contains virtually no moisture, making the Antarctic interior the world's largest desert, while the rocks that make up the rest of the continent span almost the entire age of the Earth. The wildlife along its fringes is some of the most diverse on the planet.

Yet its human history is short: Antarctica was the last continent to be discovered and explored. We have only ventured there in the past two centuries. Land was sighted for the first time in 1820, landfall was made in 1821 and people stayed for their first winter in 1899. Even the Ellsworth Mountains, where I was working in early 2011, were not explored properly until the 1960s.

In ancient times the Greeks believed there must be a land in the south to counterbalance the Arctic. They coined the word

Antarktikos

, âOpposite the Bear', referring to the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear, which hung over the northern sky.

When Antarctica was finally discovered, explorers commonly made comparisons to the polar northâoften with disastrous consequences for their expeditions. Over time, as scientific methods became established, a unique land of ice, snow and rock revealed itself. By the turn of the twentieth century enough information had been pieced together to suggest a continent lay in these polar waters. Reports were made of seemingly endless coastlines, of isolated mountain ranges and volcanoes, of ice shelves and glacier tongues that jutted tens of kilometres into the Southern Ocean. Here was a new frontier, a continent untouched by humankind, waiting to be exploredâand claimed.

Disparate groups of would-be explorers, scientists and cartographers were soon dispatched south, to see what else might be down there. The early twentieth century's Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was born. But explorers did not battle sub-zero temperatures and ice-scarred landscapes just to conquer land, bag a pole or grow an impressive beard. These expeditionary teamsâeven those intent on scoring a geographical firstâwent south to scientifically explore the new continent. The pursuit of glory was not enough: a scientific case had to be made to national academies and societies, to ensure the financial support the expeditions so desperately needed. The explorers wanted to understand what made Antarctica tick, and set off intending to bring back sledge-loads of rocks, plant and animal remains, and measurements of the air, snow and ice.

By 1912 five national teams, representing the old and new worlds, were diligently venturing beyond the edge of the known world. Although the British expedition led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen's Norwegian effort are the best known today, there were others: Nobu Shirase for Japan, Wilhelm Filchner for Germany, and Douglas Mawson for Australia and New Zealand. Their discoveries not only

enthralled the world: they changed our understanding of the planet. During this one year, at the height of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, the door to Antarctica was flung open. A frozen continent shaped by climatic extremes, and inhabited by wildlife and vegetation hitherto unknown to science, was uncovered. Feats of endurance, self-sacrifice and technological innovation laid the foundations for contemporary scientific exploration.

Regaled with tales of derring-do, the public became excited by what was being discovered in Antarctica. The expeditions of 1912 went to great lengths to publicise their findings through books, lecture tours, newspaper articles and interviews, records, radio and filmsâall were used as widely as possible, with varying degrees of success. The blend of research and exploration was a high point in science communication, as the different Antarctic teams strove to enthral and educate those at home.

Over the following decades, though, the tragic events of the era came to overshadow the amazing work accomplished, and much of this work was forgotten outside the small Antarctic scientific community. By drawing on my own experiences in the south and the rich source material from the time, I hope to illustrate why the centenary of this scientific exploration is worth celebrating, and how 1912 heralded the dawn of a new age in our understanding of the natural world.