Your Inner Fish: A Journey Into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body (6 page)

Read Your Inner Fish: A Journey Into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body Online

Authors: Neil Shubin

The fins of most fish—for example, a zebrafish (top)—have large amounts of fin webbing and many bones at the base. Lungfish captured people’s interest because like us they have a single bone at the base of the appendage.

Eusthenopteron

(middle) showed how fossils begin to fill the gap; it has bones that compare to our upper arm and forearm.

Acanthostega

(bottom) shares

Eusthenopteron

’s pattern of arm bones with the addition of fully formed digits.

For our story,

Ichthyostega

is a bit of a letdown. True, it is a remarkable intermediate in most aspects of its head and back, but it says very little about the origin of limbs because, like any amphibian, it already has fingers and toes. Another creature, one that received little notice when Save-Soderbergh announced it, was to provide real insights decades later. This second limbed animal was to remain an enigma until 1988, when a paleontological colleague of mine, Jenny Clack, who we introduced in the first chapter, returned to Save-Soderbergh’s sites and found more of its fossils. The creature, called

Acanthostega gunnari

back in the 1920s on the basis of Save-Soderbergh’s fragments, now revealed full limbs, with fingers and toes. But it also carried a real surprise: Jenny found that the limb was shaped like a flipper, almost like that of a seal. This suggested to her that the earliest limbs arose to help animals swim, not walk. That insight was a significant advance, but a problem remained:

Acanthostega

had fully formed digits, with a real wrist and no fin webbing.

Acanthostega

had a limb, albeit a very primitive one. The search for the origins of hands and feet, wrists and ankles had to go still deeper in time. This is where matters stood until 1995.

FINDING FISH FINGERS AND WRISTS

In 1995, Ted Daeschler and I had just returned to his house in Philadelphia after driving all through central Pennsylvania in an effort to find new roadcuts. We had found a lovely cut on Route 15 north of Williamsport, where PennDOT had created a giant cliff in sandstones about 365 million years old. The agency had dynamited the cliff and left piles of boulders alongside the highway. This was perfect fossil-hunting ground for us, and we stopped to crawl over the boulders, many of them roughly the size of a small microwave oven. Some had fish scales scattered throughout, so we decided to bring a few back home to Philadelphia. Upon our return to Ted’s house, his four-year-old daughter, Daisy, came running out to see her dad and asked what we had found.

In showing Daisy one of the boulders, we suddenly realized that sticking out of it was a sliver of fin belonging to a large fish. We had completely missed it in the field. And, as we were to learn, this was no ordinary fish fin: it clearly had lots of bones inside. People in the lab spent about a month removing the fin from the boulder—and there, exposed for the first time, was a fish with Owen’s pattern. Closest to the body was one bone. This one bone attached to two bones. Extending away from the fin were about eight rods. This looked for all the world like a fish with fingers.

Our fin had a full set of webbing, scales, and even a fish-like shoulder, but deep inside were bones that corresponded to much of the “standard” limb. Unfortunately, we had only an isolated fin. What we needed was to find a place where whole bodies of creatures could be recovered intact. A single isolated fin could never help us answer the real questions: What did the creature use its fins for, and did the fish fins have bones and joints that worked like ours? The answer would come only from whole skeletons.

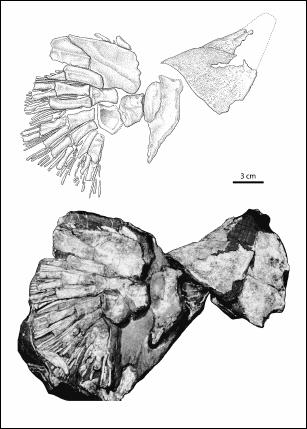

Our tantalizing fin. Sadly, we found only this isolated specimen. Stipple diagram used with the permission of Scott Rawlins, Arcadia University. Photo by the author.

For that find, we had to search almost ten years. And I wasn’t the first to recognize what we were looking at. The first were two professional fossil preparators, Fred Mullison and Bob Masek. Preparators use dental tools to scratch at the rocks we find in the field and thereby expose the fossils inside. It can take months, if not years, for a preparator to turn a big fossil-filled boulder like ours into a beautiful, research-quality specimen.

During the 2004 expedition, we had collected three chunks of rock, each about the size of a piece of carry-on luggage, from the Devonian of Ellesmere Island. Each contained a flat-headed animal: the one I found in ice at the bottom of the quarry, Steve’s specimen, and a third specimen we discovered in the final week of the expedition. In the field we had removed each head, leaving enough rock intact around it to explore in the lab for the rest of the body. Then the rocks were wrapped in plaster for the trip home. Opening these kinds of plaster coverings in the lab is much like encountering a time capsule. Bits and pieces of our life on the Arctic tundra are there, as are the field notes and scribbles we make on the specimen. Even the smell of the tundra comes wafting out of these packages as we crack the plaster open.

Fred in Philadelphia and Bob in Chicago were scratching on different boulders at the same general time. From one of these Arctic blocks, Bob had pulled out a particular small bone in a big fin of the Fish (we hadn’t named it

Tiktaalik

yet). What made this cube-shaped blob of bone different from any other fin bone was a joint at the end that had spaces for four other bones. That is, the blob looked scarily like a wrist bone—but the fins in the block that Bob was preparing were too jumbled to tell for sure. The next piece of evidence came from Philadelphia a week later. Fred, a magician with his dental tools, uncovered a whole fin in his block. At the right place, just at the end of the forearm bones, the fin had

that

bone. And

that

bone attached to four more beyond. We were staring at the origin of a piece of our own bodies inside this 375-million-year-old fish. We had a fish with a wrist.

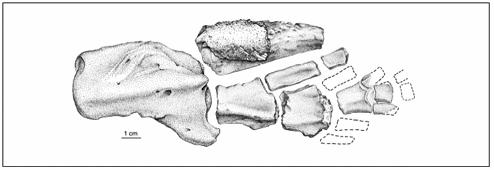

The bones of the front fin of

Tiktaalik—

a fish with a wrist.

Over the next months, we were able to see much of the rest of the appendage. It was part fin, part limb. Our fish had fin webbing, but inside was a primitive version of Owen’s one bone–two bones–lotsa blobs–digits arrangement. Just as Darwin’s theory predicted: at the right time, at the right place, we had found intermediates between two apparently different kinds of animals.

Finding the fin was only the beginning of the discovery. The real fun for Ted, Farish, and me came from understanding what the fin did and how it worked, and in guessing why a wrist joint arose in the first place. Solutions to these puzzles are found in the structure of the bones and joints themselves.

When we took the fin of

Tiktaalik

apart, we found something truly remarkable: all the joint surfaces were extremely well preserved.

Tiktaalik

has a shoulder, elbow, and wrist composed of the same bones as an upper arm, forearm, and wrist in a human. When we study the structure of these joints to assess how one bone moves against another, we see that

Tiktaalik

was specialized for a rather extraordinary function: it was capable of doing push-ups.

When we do push-ups, our hands lie flush against the ground, our elbows are bent, and we use our chest muscles to move up and down.

Tiktaalik

’s body was capable of all of this. The elbow was capable of bending like ours, and the wrist was able to bend to make the fish’s “palm” lie flat against the ground. As for chest muscles,

Tiktaalik

likely had them in abundance. When we look at the shoulder and the underside of the arm bone at the point where they would have connected, we find massive crests and scars where the large pectoral muscles would have attached.

Tiktaalik

was able to “drop and give us twenty.”

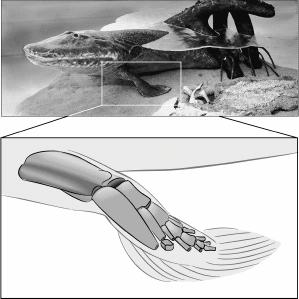

A full-scale model of

Tiktaalik

’s body (top) and a drawing of its fin (bottom). This is a fin in which the shoulder, elbow, and proto-wrist were capable of performing a type of push-up.

Why would a fish ever want to do a push-up? It helps to consider the rest of the animal. With a flat head, eyes on top, and ribs,

Tiktaalik

was likely built to navigate the bottom and shallows of streams or ponds, and even to flop around on the mudflats along the banks. Fins capable of supporting the body would have been very helpful indeed for a fish that needed to maneuver in all these environments. This interpretation also fits with the geology of the site where we found the fossils of

Tiktaalik.

The structure of the rock layers and the pattern of the grains in the rocks themselves have the characteristic signature of a deposit that was originally formed by a shallow stream surrounded by large seasonal mudflats.

But why live in these environments at all? What possessed fish to get out of the water or live in the margins? Think of this: virtually every fish swimming in these 375-million-year-old streams was a predator of some kind. Some were up to sixteen feet long, almost twice the size of the largest

Tiktaalik.

The most common fish species we find alongside

Tiktaalik

is seven feet long and has a head as wide as a basketball. The teeth are barbs the size of railroad spikes. Would you want to swim in these ancient streams?

It is no exaggeration to say that this was a fish-eat-fish world. The strategies to succeed in this setting were pretty obvious: get big, get armor, or get out of the water. It looks as if our distant ancestors avoided the fight.

But this conflict avoidance meant something much deeper to us. We can trace many of the structures of our own limbs to the fins of these fish. Bend your wrist back and forth. Open and close your hand. When you do this, you are using joints that first appeared in the fins of fish like

Tiktaalik.

Earlier, these joints did not exist. Later, we find them in limbs.