With Liberty and Justice for Some (26 page)

Read With Liberty and Justice for Some Online

Authors: Glenn Greenwald

True to his campaign rhetoric, Clinton’s presidency ushered in a series of policies that ensured a rising prison population. In the process, he converted the law-and-order mind-set from a GOP attack strategy into a bipartisan policy consensus. Like all policies enjoying bipartisan consensus, being tough on crime was thus removed from the realm of the debatable.

The right’s efforts to exploit crime to undermine Clinton were continuously thwarted by his willingness to adopt the right-wing approach to penal issues. In 1994, for instance, the GOP’s “Contract with America” included a section titled “The Taking Back Our Streets Act,” which demanded, among other things, more severe criminal punishments, longer prison sentences, mandatory sentencing requirements, and more prisons.

The bill embodies the Republican approach to fighting crime: making punishments severe enough to deter criminals from committing crimes…. The bill sets mandatory sentences for crimes involving the use of firearms, authorizes $10.5 billion for state prison construction grants, establishes truth-in-sentencing guidelines, reforms the habeas corpus appeals process [by making it more difficult for prisoners to file them], allows police officers who in good faith seized incriminating evidence in violation of the “exclusionary rule” to use the evidence in court, requires that convicted criminals make restitution to their victims, and authorizes $10 billion for local law enforcement spending.

The following year, Clinton signed into law an “anticrime” bill that largely incorporated these demands. The only real “concession” Clinton extracted from the Republicans was the inclusion in the bill of an assault weapons ban. But when he stood for reelection in 1996, Clinton heralded the bill as one of the crown jewels of his presidency, repeatedly boasting that his increased “law enforcement spending” had added 100,000 police officers to the street.

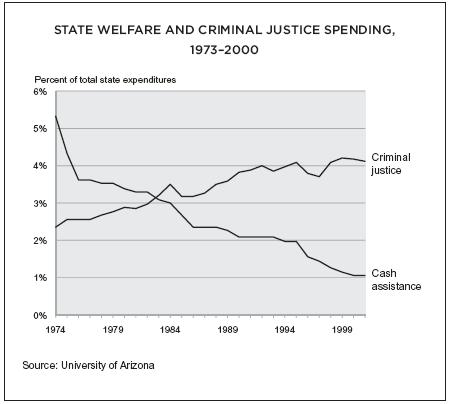

The bipartisan emphasis on law and order led to a shift in priorities across the board. Government programs were no longer focused on creating opportunities for the poor; instead, the focus was on locking them up. From Reagan’s presidency through the Clinton years, the steep rise in state spending on police and corrections was accompanied by a precipitous decline in spending on the poor.

Today, it is commonplace for politicians in both parties at the federal, state, and local levels to compete with one another over who can advocate the most draconian punishments for ordinary Americans. During the Democrats’ protracted 2008 primary fight, Hillary Clinton attacked Barack Obama by claiming that he was too liberal to win the election. Asked for specifics, her campaign pointed to a 2004 statement in which Obama had advocated the abolition of mandatory minimum sentences for federal crimes.

As president, Obama himself has demonstrated a readiness to follow his predecessors and position himself as a law-and-order politician. In April 2010, he gave an interview about “judicial activism”—that is, courts acting beyond their authority—which echoed Nixonian complaints about the Warren Court. As the

New York Times

put it, “President Obama has spoken disparagingly about liberal victories” such as

Miranda

rights and the guarantee of legal representation for indigent defendants.

Here’s another way to think of all this history. The man who initially enshrined law and order as the foundation of the nation’s federal justice system—Richard Nixon—committed serious felonies but did not spend a day in prison. The man who most popularized the no-mercy mentality—Ronald Reagan—not only spared from prison Mark Felt, an FBI official convicted of illegally spying on Americans, but himself presided over a criminal effort to fund Nicaraguan terrorists. That all ended satisfactorily for Reagan: virtually all of his top aides, and therefore Reagan himself, were shielded from accountability by his handpicked successor, George H. W. Bush, who pardoned six key conspirators who were either about to go on trial or who had already pleaded guilty or been convicted.

The man who converted the tough-on-crime crusade into bipartisan orthodoxy—Bill Clinton—abandoned his call for investigations into past political crimes as soon as he was safely elected president. In addition, of course, Clinton admitted to lying under oath during a deposition in a civil suit but was never prosecuted. He was followed by the equally tough-on-crime George W. Bush, whose entire presidency was a spree of lawbreaking. And Bush was succeeded by Barack Obama, who has engaged in Herculean efforts to shield Bush and his top aides from any investigation, and has done the same for plundering, fraud-perpetrating Wall Street elites.

The Western World’s Rogue Justice State

There is little question that this decades-long law-and-order movement is a major cause of America’s ever-expanding prison population. Numerous new laws enacted at the federal, state, and local levels have been moving the United States in the direction of longer prison terms, less leniency, and less sentencing discretion available to judges. Nationwide, politicians in both parties have established their tough-on-crime bona fides by supporting—and demanding ever-greater application of—a slew of prison-populating policies, such as “three-strikes-and-you’re-out” laws and abolition of parole.

Beyond laws deliberately intended to incarcerate people for longer periods, prison has become the punishment for an ever-broader array of transgressions, including many that, according to the JFA Institute, “pose little if any danger or harm to our society.” In fact, the United States routinely imprisons its citizens even for nonviolent crimes for which no other Western nation imposes jail terms, from petty drug offenses to writing bad checks. In April 2008, the

New York Times

reporter Adam Liptak compared the contemporary American approach to criminal justice with that of the rest of the world and found an “enormous and growing” gap: “Americans are locked up for crimes…that would rarely produce prison sentences in other countries.” For Vivien Stern, a research fellow at the prison studies center in London quoted by Liptak, the United States has become “a rogue state, a country that has made a decision not to follow what is a normal Western approach.”

The scope of criminal law has expanded so rapidly, and now includes such minor offenses, that Alex Kozinski, who is the chief judge of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the lawyer Misha Tseytlin titled a 2009 essay, with only a little irony, “You’re (Probably) a Federal Criminal.” As they put it, “Most Americans are criminals, and don’t know it, or suspect that they are but believe they’ll never get prosecuted…. Violations are so common that any attempt to go after all criminals would sweep up untold millions of people.”

As Kozinski and Tseytlin note, anyone who has ever misfiled their taxes (even inadvertently), or consumed any illegal drugs (including marijuana), or bet on a sporting event with a bookie, or lied to a government bureaucrat, or even just performed their job poorly (if it’s an occupation regulated by the federal government) has committed a federal offense for which they could be sent to prison—and for which many of their fellow citizens are now actually imprisoned. Similarly, the criminologists Beckett and Sasson report that “in 2000, police arrested more than 2 million individuals for such ‘consensual’ or ‘victimless’ crimes as curfew violations, prostitution, gambling, drug possession, vagrancy, and public drunkenness. Fewer than one in five of all arrests in that year involved people accused of the more serious ‘index’ crimes” such as assault, larceny, rape, or homicide. It should hardly be controversial that a system of criminal law that theoretically renders a substantial portion—if not an outright majority—of the citizenry subject to long prison terms is both excessive and unjust.

It is not merely the proliferation of criminal statutes that has turned America into the world’s largest prison state, but also the severity of punishment. The law professor Michael Tonry, a leading authority on crime policy, writes in his

Handbook of Crime and Punishment

that American prison sentences are “vastly harsher than in any other country to which the United States would ordinarily be compared.” According to the 2007 JFA report, “For the same crimes, American prisoners receive sentences twice as long as English prisoners, three times as long as Canadian prisoners, four times as long as Dutch prisoners, five to 10 times as long as French prisoners, and five times as long as Swedish prisoners.” Notably, these more severe punishments produce little benefit for the United States. The rates of violent crime in all those countries are lower than America’s, and their rates of property crime are comparable.

One of the most disturbing aspects of the American approach to crime is the embrace of mandatory minimum sentencing schemes, which eliminate mercy and flexibility by denying judges the ability to adjust sentences when circumstances merit. These laws force the courts to subject all convicted defendants to unyielding harshness, even when doing so produces gross injustice. The advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums has documented numerous travesties resulting from these mandatory sentencing rules, such as cases where young adults convicted of petty drug offenses were sentenced to decades in prison.

Almost every new wave of law-and-order enthusiasm has exacerbated the problem. Currently, in California alone, there are roughly 8,700 inmates serving life sentences under the “three-strikes-and-you’re-out” law; almost 3,700 of them are imprisoned under that punishment scheme despite having committed nonviolent third-offenses, such as petty theft. Close to half the states in the country have enacted some version of a “three-strikes” law. In 2003, a 5 to 4 majority of the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the claim that such mandatory life imprisonment constitutes “cruel and unusual punishment,” and thus upheld it as constitutional.

Even worse, these specific measures have given rise to a generalized mind-set of ruthlessness that pervades the entire legal system. Leniency and mercy, once the hallmarks of civilized rule, to say nothing of the great Western religions, have come to be scornfully equated with coddling, weakness, and liberalism. Particularly at the state level, where judges are elected rather than (as in the federal system) appointed for life, the political calculus—in which harsher punishments equal more votes—pushes the courts to ever-lower depths of punitive retribution. Some judges are now so eager to prove their chops, reports the

Economist

, that they “appear in campaign advertisements waving guns and bragging about how tough they are.”

One could write an entire book chronicling cases of excessive punishments that would strike any decent person as unconscionable. But to demonstrate the merciless nature of American law when it’s applied to the powerless, a few examples will suffice.

In mid-2006, Jessica Hall, a twenty-five-year-old African American unemployed mother of three, was driving on Interstate 95 through Virginia with her three children in the back and her pregnant sister—who was experiencing early contractions—sitting next to her. Traffic ground to a halt, and when it began moving again another vehicle cut Hall off. In frustration, she tossed a large McDonald’s cup filled with ice into the other car. As Eliza Fowle, a passenger in that car, described it to the

Washington Post

in February 2007: Hall “chuck[ed] a big, supersized McDonald’s cup at us. It was gross and sticky and got all over me and the front of our car, the dashboard and the windshield.”

Hall had no prior criminal record. Nobody was injured in the incident. But as the

Post

reported, Hall “was charged and convicted by a Stafford County jury of maliciously throwing a missile into an occupied vehicle, a felony in Virginia.” The jury instructions stated that “any physical object can be considered a missile. A missile can be propelled by any force, including throwing.” By the time of her trial, Hall had spent more than a month in jail, leaving her small children without a parent to care for them: Hall’s husband, a marine, was serving in Iraq. The jury sentenced Hall to two years in prison, the minimum penalty allowed under the law. The

Post

article describes the aftermath.

[Hall] never fathomed that it would land her in jail for the first time in her life, wearing a standard-issue jumpsuit frayed up both legs and learning to curl her hair using toilet paper…. “I passed out when they said guilty, two years,” she added. “I became a convicted felon.”

“I think that this is way too much of a punishment for her actions. This is just to me absolutely ridiculous,” Fowle said. Community service would have made more sense, she said. Hall said she has cried every day she has spent locked up and wakes most days to find clumps of hair on her pillow from the stress. She shares a cell with two other women and spends 19 hours a day in the cell, she said.

After the case received substantial local media attention and Hall had spent seven weeks in prison, the judge suspended her sentence on the condition of five years of good behavior. She told reporters that she had planned to go to nursing school but now believed her status as a convicted felon would preclude that. Even the “victim” was so horrified by what happened to Hall that she said she would be reluctant to report a crime in the future.