Why She Buys (17 page)

Authors: Bridget Brennan

• Older people often help more with their grandkids than they ever could have imagined they would

.

Grandparent contributions of time and money have become an economic force. In many families, grandparents greatly assist with child care, education costs, and the funding of the kids’ “extras.” Studies show that as many as 22 percent of grandparents are helping to pay college tuition for their grandkids.

34

Addressing grandparents as an audience when selling products and services for kids is a smart idea—because they might be the only adults in the family who can afford them.

G

ENERATION

XXXL

T

here’s no real need to look at obesity statistics when a stroll through any American mall will do. We’re getting bigger as a nation and a planet. Our adults are big, our kids are big, and even our pets are big. (There is a burgeoning market in controlling pet obesity, but I digress.)

Women have higher obesity rates than men, according to the Centers for Disease Control. More than one-third of women ages twenty to seventy-four are obese.

35

The rates are even higher for Mexican American women (52 percent) and African American women (53 percent). We all know that female obesity carries a greater social stigma than its male counterpart. Women are expected to be thin and beautiful, while men are forgiven for being heavy and bald. It’s a classic double standard. Obesity, however, knows no age: about 27 percent of kids in the United States are currently considered obese, and often they are the children of obese parents.

36

In America, the average weight for a woman is 164 pounds.

37

This is a nearly twenty-five-pound increase since 1960. (Women also grew an inch taller during this time, with the average height shifting from 5’3” to 5’4”.) The health impact of obesity is well documented, but its implications for industries that sell to women have been less reported. Few have examined the subject from a consumer-products point of view, with the notable exceptions of the food and diet industries. Obesity is a global problem, and ironically, developing countries have to battle food on two fronts, by trying to eliminate both obesity and malnutrition at the same time. Obesity rates have tripled in Great Britain since 1982, more than doubled in Australia, and risen 97 percent in China in the past decade.

38

What’s driving this unfortunate trend? The usual suspects—a sedentary lifestyle combined with oversized portions of unhealthy, processed food. Americans work more hours than any other population in the industrialized world. Logging nearly 2,000 hours of work each year, most Americans find it difficult to find the time to exercise and eat right. When combined with women’s typically busy schedules, which often include

transporting kids, cooking, cleaning, shopping, and scheduling the cable installer, the outlook is pretty bleak that the tide will reverse itself anytime soon. When you look back at a day in the life of Jamie, whose schedule was documented earlier in this chapter, it’s hard to imagine where she might be able to squeeze in some quality exercise and cooking time. She says she does, but not as often as she’d like.

Our extreme eating habits and huge portions are driving us to spend ever more money to get the weight off. Between $33 billion and $55 billion is already spent annually on weight-loss products and services.

39

Life Time Fitness is a fast-growing business in the United States that caters to the fitness and nutritional needs of families. In enormous “gyms” averaging 110,000 square feet—which can only be described as a cross between a country club and a mall—whole families participate in healthy activities ranging from eating low-carb meals in its restaurants to attending Pilates classes and swimming lessons. While at the club, members can check their e-mail via Wi-Fi, get a quick haircut at the center’s Aveda salon, or drink a hot beverage at Caribou Coffee—all while a professional staff watches the kids in a supervised child care center. The company has nearly one hundred locations in the United States.

Life Time Fitness has created a new format that caters to the modern (and more often than not plump) American family. Such fitness multiplexes offer something for everyone, making it easy for mothers to take their families along with them while they work out. The gyms are beautiful and stigma-free, and designed for the reality of modern family lives.

Insights for business:

•

Plus-size women are becoming the norm in the United States

.

The average American woman is a size fourteen, and the numbers aren’t expected to change anytime soon—though this reality is not reflected broadly in apparel offerings or media portrayals. Women of all sizes want beautiful clothes, elegant bridal gowns, lovely prom dresses, fashionable shoes, and cool workout gear. They don’t want to wear frumpy clothes any more than thin women do. If a woman wears a large dress size, it means that her hands and feet are larger, too, creating implications for shoes, jewelry, and handbag design, as well as furniture, housewares, and even cars.

•

Helping women solve their time conundrum is the key to helping them eat well and work out

.

Finding ways to help women manage their family and work responsibilities in order to exercise or eat well is a compelling offering that companies such as Life Time Fitness and Curves are leveraging for profit.

•

Larger women will often invest in makeup, nail, and hair care products, because these are for parts of the body unaffected by their weight

.

This is one theory behind the explosion of nail salons across the country. If someone has a hard time controlling her weight, she’ll take care of the parts of her body she

can

control—her hair, nails, and skin. It’s another possible explanation for the irrationally large amounts of handbags and shoes that flood the market every season. A purse or shoe will almost always fit, and one doesn’t need a potentially humiliating trip to the dressing room to try them on.

Women Around the World:

The Importance of Cultural Context

W

HEN

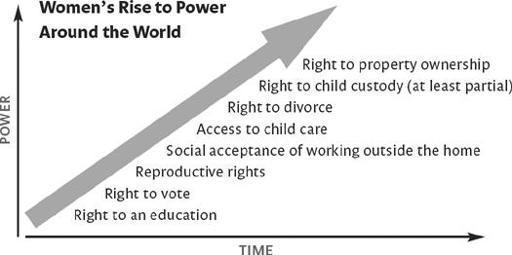

you think of the immense variety in the lives of women around the world, it’s helpful to view different countries as being on a continuum of progress. Industrialized nations are the most progressive when it comes to women’s participation in the public sphere, and this is reflected in the robustness of their economies. The emerging economies of India, China, Russia, and Brazil still lag behind the industrialized nations but are making headway. Unsurprisingly, most developing countries still have a long way to go when it comes to enabling women to become full contributors to their economies. History tells us that women’s participation in the commercial economy follows a pattern:

When it comes to global growth and expansion, many Western companies have India and China firmly in their crosshairs. It’s worth taking a moment to look at the lives of women in those nations from a top-line perspective. They are the power purchasers of the emerging economies.

60-

SECOND OVERVIEW

OVERVIEW

T

HE

W

OMEN OF

I

NDIA

H

aving made two trips to India to better understand the country’s women and its culture, I left with more questions than answers. If there is one country that defies generalizations, it’s India. With multitudes of languages, religions, traditions, cuisines, and forms of entertainment, it’s endlessly colorful and nearly impossible to pin down. There are, however, some broad themes impacting the women of India that are important to understand for any company entering the market. The crux of the matter is this: Indian women, especially those of the middle and upper classes, are caught squarely between modernity and tradition.

It’s true that women are slowly entering the paid workforce in India, but their participation lags that of other developing countries. Some still frown upon educated women working outside the home after marriage and childbirth, but more women continue to take jobs as opportunities pour into the country. Women’s employment participation outside the home grew to 31 percent in 2005 from 26 percent in 2000, the first rise seen in decades.

40

The growth of private airlines and call centers has thrust working women into public view as flight attendants and call-center employees. On the other end of the spectrum, the vast majority of rural women are self-employed, engaged in activities such as growing food, making handicrafts, and doing all manner of work to bring money into their families. Countless millions of women work at the subsistence level in rural India.

In this hierarchical society, wife and mother are still the most highly valued roles a woman can play, no matter

what her caste (hereditary social class). Women wield a tremendous amount of “informal” authority in the private sphere. They consider themselves to be the primary decision makers for their families in almost every consumer category. With nearly five hundred million women in the country, to say that Indian women are an economic force is kind of like saying Bollywood makes a lot of movies—it’s an understatement.

Culturally speaking, women are subject to an enormous amount of social control. There are implicit and explicit behavioral codes, social codes, and religious codes that they’re expected to follow. Women in their late thirties and forties in particular struggle with this. “Our mothers are living the traditional roles,” says Shefalee Vasudev, editor of

Marie Claire

magazine in India. “Some daughters rebel totally, some rebel partially, and some don’t rebel at all. There are curbs on personal freedom and codes for women. It won’t be resolved in one generation. The generations after us—the ones to come—will have it easier.”

The primary religion in India is Hinduism, but the country also has one of the most enormous Muslim populations in the world. Socially, India is conservative, especially when it comes to love and romance. Dating openly is rare, and public displays of affection are frowned upon, even between married couples. Indian movies have only started showing a chaste kiss between two characters within the past decade. Homosexuality is not discussed, and its existence is rarely acknowledged. Women are expected to be pure and chaste.

M

ARRIAGE

: T

HE

D

EFINITION OF

S

UCCESS FOR

Y

OUNG

W

OMEN

A young woman before marriage is considered “held in trust” by her parents. Most women (and men) live with

their parents until they get married. When women marry, it’s not uncommon for them to move in with their husband’s parents and become their caregivers. The average age of marriage is still just under twenty. In Indian society, marriage is the most important part of a person’s life, and from the time a baby is born, his or her parents worry about making a good match for the child. Even among the wealthiest classes, who may send their daughters to college abroad, a good marriage is often considered more important than a good career. However, new research shows that most housewives now want to be wage-earning women. This new attitude is combined with a slowdown in India’s birthrate (which makes it easier for women to work outside the home) as well as increasing social legitimacy for women’s education. Businesses, in the form of “office jobs,” provide a socially acceptable space for women to participate in the public sphere alongside men. However, working in retail or in restaurants and coffee shops is considered lower-class work that is inappropriate for well-raised young women.