Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (29 page)

Authors: Michael Shermer

Tags: #Creative Ability, #Parapsychology, #Psychology, #Epistemology, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #Philosophy, #Creative ability in science, #Skepticism, #Truthfulness and falsehood, #Pseudoscience, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Belief and doubt, #General, #Parapsychology and science

The existence of living fossils (organisms that have not changed for millions of years) simply means that they evolved a structure adequate for their relatively static and unchanging environment, so they stopped once they could maintain their ecological niche. Sharks and many other sea creatures are relatively unchanged over millions of years, while other sea creatures, such as marine mammals, have obviously changed rapidly and dramatically. Evolutionary change or lack of change, as the case may be, all depends on how and when a species' immediate environment changes.

23. The incipient structure problem refutes natural selection. A new structure that evolves slowly over tune would not provide an advantage to the organism in its beginning or intermediate stages, only when it is completely developed, which can only happen by special creation. What good is 5 percent of a wing, or 55 percent? You need all or nothing.

A poorly developed wing may have been a well-developed something else, like a thermoregulator for ectothermic reptiles (who depend on external sources of heat). And it is not true that incipient stages are completely useless. As Richard Dawkins argues in

The Blind Watchmaker

(1986) and

Climbing Mount Improbable

(1996), 5 percent vision is significantly better than none and being able to get airborne for any length of time can provide an adaptive advantage.

24. Homologous structures (the wing of a bat, the flipper of a whale, the arm of a human) are proof of intelligent design.

By invoking miracles and special providence, the creationist can pick and choose anything in nature as proof of God's work and then ignore the rest. Homologous structures actually make no sense in a special creation paradigm. Why should a whale have the same bones in its flipper as a human has in its arm and a bat has in its wing? God has a limited imagination? God was testing out the possibilities of His designs? God just wanted to do things that way? Surely an omnipotent intelligent designer could have done better. Homologous structures are indicative of descent with modification, not divine creation.

25. The whole history of evolutionary theory in particular and science in general is the history of mistaken theories and overthrown ideas. Nebraska Man, Piltdown Man, Calaveras Man, and

Hesperopithecus

are just a few of the blunders scientists have made. Clearly science cannot be trusted and modern theories are no better than past ones.

Again, it is paradoxical for creationists to simultaneously draw on the authority of science and attack the basic workings of science. Furthermore, this argument reveals a gross misunderstanding of the nature of science. Science does not just change. It constantly builds upon the ideas of the past, and it

is

cumulative toward the future. Scientists do make mistakes aplenty and, in fact, this is how science progresses. The self-correcting feature of the scientific method is one of its most beautiful features. Hoaxes like Piltdown Man and honest mistakes like

Hesperopithecus

are, in time, exposed. Science picks itself up, shakes itself off, and moves on.

Debates and Truth

These twenty-five answers only scratch the surface of the science and philosophy supporting evolutionary theory. If confronted by a creationist, we would be wise to heed the words of Stephen Jay Gould, who has encountered creationists on many an occasion:

Debate is an art form. It is about the winning of arguments. It is not about the discovery of truth. There are certain rules and procedures to debate that really have nothing to do with establishing fact—which they are very good at. Some of those rules are: never say anything positive about your own position because it can be attacked, but chip away at what appear to be the weaknesses in your opponent's position. They are good at that. I don't think I could beat the creationists at debate. I can tie them. But in courtrooms they are terrible, because in courtrooms you cannot give speeches. In a courtroom you have to answer direct questions about the positive status of your belief. We destroyed them in Arkansas. On the second day of the two-week trial, we had our victory party! (Caltech lecture, 1985)

11

Science Defended, Science Defined

Evolution and Creationism at the Supreme Court

On August 18, 1986, a press conference was held at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., to announce the filing of an

amicus curiae

brief on behalf of seventy-two Nobel laureates, seventeen state academies of science, and seven other scientific organizations. This brief supported the appellees in

Edwards v. Aguillard,

the Supreme Court case testing the constitutionality of Louisiana's Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science Act, an equal-time law passed in 1982 requiring, essentially, that the Genesis version of creation be taught side-by-side with the theory of evolution in public school classrooms in Louisiana. Attorneys Jeffrey Lehman and Beth Shapiro Kaufman from the firm of Caplin and Drysdale, Nobel laureate Christian Anfinsen, biologist Francisco Ayala from the University of California, Davis, and paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould from Harvard University faced a room filled with television, radio, and newspaper reporters from across the country.

Gould and Ayala made opening statements, and a statement by Nobel laureate Murray Gell-Mann was read in absentia. The emotional commitment of these representatives from the scientific community was clear from the outset and baldly disclosed in their statements. Gould noted, "As a term, creation-science is an oxymoron—a self-contradictory and meaningless phrase—a whitewash for a specific, particular, and minority religious view in America—Biblical literalism." Ayala added, "To claim that the statements of Genesis are scientific truths is to deny all the evidence. To teach such statements in the schools as if they were science would do untold harm to the education of American students, who need scientific literacy to prosper in a nation that depends on scientific progress for national security and for individual health and economic gain." Gell-Mann concurred with Ayala on the broad, national scope of the problem but went further, saying, in no uncertain terms, that this was an assault on all science:

I should like to emphasize that the portion of science that is attacked by the statute is far more extensive than many people realize, embracing very important parts of physics, chemistry, astronomy, and geology as well as many of the central ideas of biology and anthropology. In particular, the notion of reducing the age of the earth by a factor of nearly a million, and that of the visible expanding universe by an even larger factor, conflicts in the most basic way with numerous robust conclusions of physical science. For example, fundamental and well-established principles of nuclear physics are challenged, for no sound reason, when "creation-scientists" attack the validity of the radioactive clocks that provide the most reliable methods used to date the earth.

Reviews of the brief appeared in a broad range of publications, including

Scientific American, Nature, Science, Omni, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Science Teacher,

and

California Science Teacher's Journal.

The

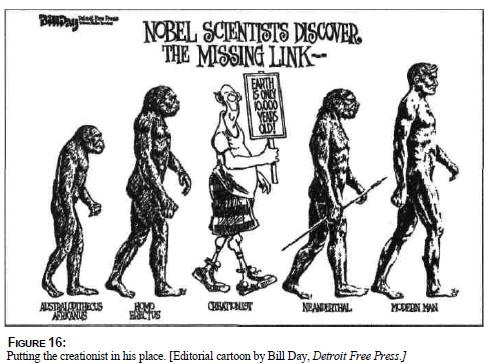

Detroit Free Press

even published an editorial cartoon in which a creationist joins the famous evolutionary "march of human progress" (figure 16).

Equal Time or All the Time?

In general, creationists are Christian fundamentalists who read the Bible literally—when Genesis speaks of the six days of creation, for example, it means six 24-hour days. In particular, of course, there are many different types of creationists, including young-Earth creationists, who hold to the 24-hour-day interpretation; old-Earth creationists, who are willing to take the biblical days as figurative speech representing geological epochs; and gap-creationists, who allow for a gap of time between the initial creation and the rise of humans and civilization (thus adapting to scientific notions of deep time, dating back billions of years).

Card-carrying creationists are small in number. But what they lack in numbers they make up in volume. And they have been able to touch the nerve that somewhere deep in the national psyche connects many Americans to our country's religious roots. We may be a pluralistic society—melting pots, salad bowls, and all that—but Genesis remains at our beginning. A 1991 Gallup poll found that 47 percent of Americans believed that "God created man pretty much in his present form at one time within the last ten thousand years." A centrist view, that "Man has developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life, but God guided this process, including man's creation," was held by 40 percent of Americans. Only 9 percent believed that "Man has developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life. God had no part in this process." The remaining 4 percent answered, "I don't know" (Gallop and Newport 1991, p. 140).

Why, then, is there a controversy? Because 99 percent of scientists take the strict naturalist view shared by only 9 percent of Americans. This is a startling difference. It would be hard to imagine any other belief for which there is such a wide disparity between the person on the street and the expert in the ivory tower. Yet science is the dominant force in our culture, so in order to gain respectability and, what is more important for creationists, access to public school science classrooms, creationists have been forced to deal with this powerful minority. Over the past eighty years, creationists have used three basic strategies to press their religious beliefs. The Louisiana case was the culmination of a series of legal battles that began in the 1920s and may be grouped into the following three approaches.

Banning Evolution

In the 1920s, a perceived degeneration in the moral fiber of America was linked to Darwin's theory of evolution. For example, a supporter of fundamentalist orator William Jennings Bryan commented in 1923, "Ramming poison down the throats of our children is nothing compared with damning their souls with the teaching of evolution" (in Cowen 1986, p. 8). Fundamentalists rallied to check the moral decline by removing evolution from the public schools. In 1923, Oklahoma passed a bill offering free textbooks to public schools on the condition that neither the teachers nor the textbooks mentioned evolution, and Florida went even further by passing an antievolution law. In 1925, the Butler Act, which made it "unlawful for any teacher in any of the Universities, Normals and all other public schools of the state ... to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals" (in Gould 1983a, p. 264), was passed by the Tennessee legislature. This act was viewed as an obvious violation of civil liberties and resulted in the famous 1925 Scopes "Monkey Trial," which has been well documented by Douglas Futuyma (1983), Gould (1983a), Dorothy Nelkin (1982), and Michael Ruse (1982).

John T Scopes was a substitute teacher who volunteered to provide the test case by which the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) could challenge Tennessee's antievolution law. The ACLU intended to take the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, if necessary. Clarence Darrow, the most famous defense attorney of the day, provided legal counsel for Scopes, and William Jennings Bryan, three-time presidential candidate and known voice of biblical fundamentalism, served as defender of the faith for the prosecution. The trial was labeled the "trial of the century," and the hoopla surrounding it was intense; it was, for example, the first trial in history for which daily updates were broadcast by radio. The two giants pontificated for days, but in the end Scopes was found guilty and fined $100 by Judge Raulston (Scopes did, indeed, break the law). Because of a little-known catch in Tennessee law, which required all fines above $50 to be set by a jury, not a judge, the court overturned Scopes's conviction, leaving the defense nothing to appeal. It never was taken to the U.S. Supreme Court, and the law stood on the books until 1967.

Most people think that Scopes, Darrow, and the scientific community scored a great victory in Tennessee. H. L. Mencken, covering the trial for the

Baltimore Sun,

summarized it and Bryan this way: "Once he had one leg in the White House and the nation trembled under his roars. Now he is a tinpot pope in the Coca-Cola belt and a brother to the forlorn pastors who belabor half-wits in galvanized iron tabernacles behind the railroad yards. ... It is a tragedy, indeed, to begin life as a hero and to end it as a buffoon" (in Gould 1983a, p. 277). But, in fact, there was no victory for evolution. Bryan died a few days after the trial ended, but he had the last laugh, as the controversy stirred by the trial made others, particularly textbook publishers and state boards of education, reluctant to deal with the theory of evolution in any manner. Judith Grabiner and Peter Miller (1974) compared high school textbooks before and after the trial: "Believing that they had won in the forum of public opinion, the evolutionists of the late 1920s in fact lost on their original battleground— teaching of evolution in the high schools—as judged by the content of the average high school biology textbooks [which] declined after the Scopes trial." A trial that seems comical in retrospect was really a tragedy, as Mencken concluded: "Let no one mistake it for comedy, farcical though it may be in all its details. It serves notice on the country that Neanderthal man is organizing in these forlorn backwaters of the land, led by a fanatic, rid of sense and devoid of conscience. Tennessee, challenging him too timorously and too late, now sees its courts converted into camp meetings and its Bill of Rights made a mock of by its sworn officers of the law" (in Gould 1983a, pp. 277-278).