Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (47 page)

Authors: Michael Shermer

Tags: #Creative Ability, #Parapsychology, #Psychology, #Epistemology, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #Philosophy, #Creative ability in science, #Skepticism, #Truthfulness and falsehood, #Pseudoscience, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Belief and doubt, #General, #Parapsychology and science

Whereas most scientists do not dare publish such controversial notions until late in their careers, by the time he began studying physics at MIT Tipler was already entertaining ideas in the borderlands between science and science fiction:

I became aware of time travel in the dorm when a bunch of us physics students discussed it. We would talk about the real far-out ideas in physics, such as the many-histories interpretation of physics. I read Godel's paper on closed time-like curves. I was fascinated by that and went and got a copy of the second volume of

Albert Einstein, Philosopher/Scientist.

I read that Einstein became aware of this possibility when he was generating the general theory of relativity, and he even discussed the Godel paper. That gave me confidence because the majority of the community of physicists may not believe in the possibility of time travel, but Kurt Godel and Albert Einstein did, and those were not lightweight scientists. (1995)

Tipler's first published paper appeared in the prestigious

Physical Review.

Written while he was a graduate student, it proposed that a time machine might actually be possible. "Rotating Cylinders and the Possibility of Global Causality Violation" was revolutionary for its time; it was even adapted for a short story by science fiction author Larry Niven.

While earning his Ph.D. in physics, working with the general relativity group at the University of Maryland, Tipler was laying the groundwork for his later books. In 1976, Tipler began postdoctoral work at the University of California, Berkeley, where he met British cosmologist John Barrow, also a postdoc. Tipler and Barrow discussed a manuscript by Brandon Carter which described the Anthropic Principle. "We thought it would be a good idea to take the idea and expand it out. And that became the

Anthropic Cosmological Principle.

In our last chapter we combined the idea from Freeman Dyson [1979] of life going on forever, with physical reductionism and global general relativity; the Omega Point Theory then follows." Tipler's steps in reasoning sound logical, but his conclusions push the limits of science:

I wanted our book to be completely general, so I said to myself, well, what about the flat universe and the closed universe [instead of an open universe]? One of the problems in the closed universe is communication because we have event horizons everywhere. So I said to myself, that wouldn't be a problem if there were no event horizons. If there were no event horizons, what would the c-boundary be like?

Aha,

it would be a single point, and a single-point end of time reminded me of Teilhard's Omega Point, which he identified with God. So I thought maybe there is a religious connection here. (1995)

Barrow and Tipler's work is an attack on the Copernican Principle, which states that man has no special place or purpose in the cosmos. According to the Copernican Principle, our sun is merely one of a hundred billion stars on the outskirts of an average galaxy, itself one of a hundred billion (or more) galaxies in the known universe that cares not one iota for humanity. By contrast, Carter, Barrow, and Tipler's Anthropic Principle insists that humans do have a significant role in the cosmos, both in its observation and its existence. Carter (1974) takes the part of Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle that says that the observation of an object changes it and extrapolates this part from the atomic level (where Heisenberg was operating) to the cosmological level: "What we can expect to observe must be restricted by the conditions necessary for our presence as observers." In its weak form—the Weak Anthropic Principle—Barrow and Tipler contend quite reasonably that for the cosmos to be observed, it must be structured in such a way as to give rise to observers: "The basic features of the Universe, including such properties as its shape, size, age and laws of change, must be observed to be of a type that allows the evolution of observers, for if intelligent life did not evolve in an otherwise possible universe, it is obvious that no one would be asking the reason for the observed shape, size, age and so forth of the Universe" (1986, p. 2). The principle is tautological: in order for the universe to be observed, there must be observers. Obviously. Who would disagree? The controversy generated by Carter, Barrow, and Tipler lies not with the Weak Anthropic Principle but with the Strong Anthropic Principle, the Final Anthropic Principle, and the Participatory Anthropic Principle. Barrow and Tipler define the Strong Anthropic Principle as "The Universe must have those properties which allow life to develop within it at some stage in its history" and the Final Anthropic Principle as "Intelligent information-processing must come into existence in the Universe, and, once it comes into existence, it will never die out" (pp. 21-23).

That is, the universe must be exactly like it is or there would be no life; therefore, if there were no life, there could be no universe. Further, the Participatory Anthropic Principle states that once life is created (which is inevitable), it will change the universe in such a way that it assures its, and all life's, immortality: "The instant the Omega Point is reached life will have gained control of all matter and forces not only in a single universe, but in all universes whose existence is logically possible; life will have spread into all spatial regions in all universes which could logically exist, and will have stored an infinite amount of information, including all bits of knowledge which it is logically possible to know. And this is the end" (p. 677). This Omega Point, or what Tipler calls a "singularity" of space and time, corresponds to "eternity" in traditional religion. Singularity is also the term used by cosmologists to describe the theoretical starting point of the Big Bang, the center point of a black hole, and the possible ending point of the Big Crunch. Everything and everyone in the universe will converge at this final end point.

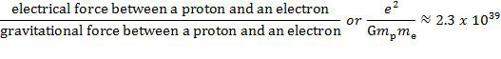

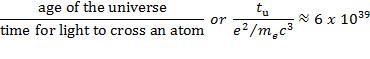

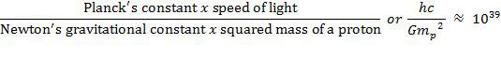

Like Dr. Pangloss, Barrow and Tipler relate their incredible claims to a number of seemingly coincidental conditions, events, and physical constants that

must

be a certain way or else there could be no life. For example, they find great meaning in the fact that

approximately equals the

They also think it significant that

approximately equals the square root of the number of protons in the observable universe

or

Change these relationships significantly and our universe and life as we know it could not exist; thus, they conclude, this is not just the best of all possible worlds, it is the

only

possible world. Barrow and Tipler assume that this relationship, known as Dirac's Large Numbers Hypothesis, is no coincidence. Change any of the constants and the universe would be different enough that life as we know it could not exist, and neither could the universe. There are two problems with this argument.

1.

The Lottery Problem.

Our universe may only be one bubble among many bubble universes (with the whole thing being a multiverse), each one of which has slightly different laws of physics. According to this controversial theory recently pioneered by Lee Smolin (1992) and Andrei Linde (1991), each time a black hole collapses, it collapses into a singularity like the entity out of which our universe was created. But as each collapsing black hole creates a new baby universe, it alters the laws of physics slightly within that baby universe. Since there have probably been billions of collapsed black holes, there are billions of bubbles with slightly different laws of physics. Only those bubbles with laws of physics like ours can give rise to our types of life. Whoever happens to be in one of these bubbles will think that theirs is the only bubble and thus that they are unique and specially designed. It's like the lottery—it is extremely unlikely that any one person will win, but someone

will

win! Astrophysicist and science writer John Gribbin even suggests an analogy with evolution, where each new bubble is mutated to be slightly different from its parent, and the bubbles are competing with one another, "jostling for spacetime elbow room within superspace" (1993, p. 252). Caltech scientist Tom McDonough and science writer David Brin (1992) wrote melodramatically, "Perhaps we owe our existence, and the convenient perfection of our physical laws, to the trial-and-error evolution of untold generations of prior universes, a chain of mother-and-child cosmoses, each of them spawned in the nurturing depths of black holes."

Much is explained by this model. Our particular bubble universe is unique, but it is not the only bubble nor is it in itself unique in any designed sense. The set of conditions that came together to create life is merely contingent—a conjuncture of events without design. There is no need to posit a higher intelligence. In the long term, this model makes historical sense. From the time of Copernicus, our perspective on the cosmos has been expanding: solar system, galaxy, universe, multiverse. The bubble universe is the next logical step, and it is the best explanation yet for the apparent design of the laws of physics.

2.

The Design Problem.

As David Hume argued in his brilliant analysis of causality in

An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

(1758), an orderly world with everything in its rightful place only seems that way because of our experience of it as such. We have perceived nature as it is, so for us this is how the world

must

be designed. Alter the universe and the world, and you alter life in such a way that

its

universe and world would appear as it must be for that observer, and no other. The Weak Anthropic Principle says the universe must be as it is to be observed, but it should include the modifier "by its

particular

observers." As Richard Hardison noted, "Aquinas considered two eyes to be the ideal number and this was evidence of God's existence and benevolence. However, is it not likely that two seems the proper number of eyes simply because that is the pattern to which we have become accustomed?" (1988, p. 123). The so-called coincidental relationships between the physical constants and large numbers of the universe can be found just about anywhere by someone with patience and a turn for numbers. For example, John Taylor, in his book

The Great Pyramid

(1859), observed that if you divide the height of the pyramid into twice the side of its base, you get a number close to TC; he also thought he had discovered the length of the ancient cubit as the division of the Earth's axis by 400,000—both of which Taylor found to be too incredible to be coincidental. Others discovered that the base of the Great Pyramid divided by the width of a casing stone equals the number of days in the year and that the height of the Great Pyramid multiplied by 10

9

approximately equals the distance from the Earth to the Sun. And so on. Mathematician Martin Gardner analyzed the Washington Monument, "just for fun," and "discovered" the property of fiveness to it: "Its height is 555 feet and 5 inches. The base is 55 feet square, and the windows are set at 500 feet from the base. If the base is multiplied by sixty (or five times the number of months in a year) it gives 3,300, which is the exact weight of the capstone in pounds. Also, the word 'Washington' has exactly ten letters (two times five). And if the weight of the capstone is multiplied by the base, the result is 181,500—a fairly close approximation of the speed of light in miles per second" (1952, p. 179). After musing that "it should take an average mathematician about 55 minutes to discover the above 'truths,'" Gardner notes "how easy it is to work over an undigested mass of data and emerge with a pattern, which at first glance, is so intricately put together that it is difficult to believe it is nothing more than the product of a man's brain" (p. 184). The skeptics' skeptic, Gardner leaves "it to readers to decide whether they should opt for OPT [the Omega Point Theory] as a new scientific religion superior to Scientology ... or opt for the view that OPT is a wild fantasy generated by too much reading of science fiction" (1991b, p. 132).