Who Owns the Future? (30 page)

Read Who Owns the Future? Online

Authors: Jaron Lanier

Tags: #Future Studies, #Social Science, #Computers, #General, #E-Commerce, #Internet, #Business & Economics

We who are enthusiastic about the Internet love the fact that so many people contribute to it. It’s hard to believe that once upon a time people worried about whether anyone would have anything worthwhile to say online! I have not lost even a tiny bit of this aspect of our formative idealism from decades ago. I still find that when I put my trust in people, overall they come through. People at large always seem to be more creative, good-willed, and resourceful than one might have guessed.

The problem is that mainstream Internet idealism is still wedded to a failed melodrama that applies our enthusiasms perversely against us. A digital orthodoxy that I find to be overbearing can only see one narrow kind of potential failure of the Internet, and invests all its idealism toward avoiding that one bad outcome, thus practically laying out invitations to a host of other avoidable failures.

From the orthodox point of view, the Internet is a melodrama in which an eternal conflict is being played out. The bad guys in the melodrama are old-fashioned control freaks like government

intelligence agencies, third-world dictators, and Hollywood media moguls, who are often portrayed as if they were cartoon figures from the game Monopoly. The bad guys want to strengthen copyright law, for instance. Someone trying to sell a movie is put in the same category as some awful dictator.

The good guys are young meritorious crusaders for openness. They might promote open-source designs like Linux and Wikipedia. They populate the Pirate parties.

The melodrama is driven by an obsolete vision of an open Internet that is already corrupted beyond recognition, not by old governments or industries that hate openness, but by the new industries that oppose those old control freaks the most.

A personal example illustrates this. Up until around 2010, I enjoyed a certain kind of user-generated content very much. In my case it was forums in which musicians talked about musical instruments.

For years I was warned that old-fashioned control freaks like government censors or media moguls could separate me from my beloved forums. A scenario might be that a forum would be hosted on some server where another user happened to say something terrorist-related, or upload pirated content.

Under some potential legislation that’s been proposed in the United States, a server like that might be shut down. So my participation in and access to nonmogul content would be at risk in a mogul-friendly world. This possibility is constantly presented as the horrible fate we must all strive to avoid.

It’s the kind of thing that has happened under oppressive regimes around the world, so I’m not saying there is no potential problem. I must point out, however, that Facebook is

already

removing me from the participation I used to love, at least on terms I can accept.

Here is how: Along with all sorts of other contact between people, musical instrument conversations are moving more and more into Facebook. In order to continue to participate, I’d have to accept Facebook’s philosophy, which includes the idea that third parties would pay to be able to spy on me and my family in order to find the best way to manipulate what shows up on the screen in front of us.

You might view my access to musical instrument forums as an inconsequential matter, and perhaps it is, but then what is consequential about the Internet in that case? You can replace musical instruments with political, medical, or legal discussions. They’re all moving under the cloak of a spying service.

You might further object that it’s all based on individual choice, and that if Facebook wants to offer us a preferable free service, and the offer is accepted, that’s just the market making a decision. That argument ignores network effects. Once a critical mass of conversation is on Facebook, then it’s hard to get conversation going elsewhere. What might have started out as a choice is no longer a choice after a network effect causes a phase change. After that point we effectively have less choice. It’s no longer commerce, but soft blackmail.

And it’s not Facebook’s fault! We, the idealists, insisted that information be demonetized online, which meant that services about information, instead of the information itself, would be the main profit centers.

That inevitably meant that “advertising” would become the biggest business in the “open” information economy. But advertising has come to mean that third parties pay to manipulate the online options in front of people from moment to moment. Businesses that don’t rely on advertising must utilize a proprietary channel of some kind, as Apple does, forcing connections between people even more out of the commons, and into company stores. In either case, the commons is made less democratic, not more.

To my friends in the “open” Internet movement, I have to ask: What did you think would happen? We in Silicon Valley undermined copyright to make commerce become more about services instead of content: more about our code instead of their files.

The inevitable endgame was always that we would lose control of our own personal content, our own files.

We haven’t just weakened old-fashioned power mongers. We’ve weakened ourselves.

Emphasizing the Middle Class Is in the Interests of Everyone

Figuring out how advancing digital technology can encourage middle classes is not only an urgent task, but also a way out of the dismal competition between “liberal” and “conservative” economics.

To a libertarian or “austerian” I say: If we desire some form of markets or capitalism, we must live in a bell-shaped world, with a dominant middle class, for that is where customers come from. Neither a petro-fiefdom, a military dictatorship, nor a narco-state can support authentic internal market development, and neither does a winner-take-nearly-all network design.

Similarly, anyone interested in liberal democracy must realize that without a dominant middle class, democracy becomes vulnerable. The middle of the bell has to be able to outspend the rich tip. As the familiar quote usually attributed to Supreme Court justice Louis D. Brandeis goes, “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

*

*

I have been unable to find an original attribution for this quote, so am not certain it is authentic. Once I cited a quote of Einstein’s (“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler”) and was informed by an Einstein biographer that there was no evidence he had said it. Then I met a woman who had known Einstein and heard him say it! In this case, I have no idea, but it’s a super quote, whoever said it.

Even for those who might dispute the primacy of either markets or democracy, the same principle will hold. A strong middle class does more to make a country stable and successful than anything else. In this, the United States, China, and the rest of the world can agree.

Another basic function of the design of power must be to facilitate long-term thinking. Is it possible to invest in something that will pay off in thirty years or a hundred, or is everything about the next quarter, or even the next quarter of a millisecond?

These two functions of the design of power in a civilization will turn out to be deeply intertwined, but the middle class will be our immediate concern.

A Better Peak Waiting to Be Discovered

We’re used to getting Google and Facebook for free, and my advocating otherwise puts me in the position of having to sound like the Grinch stealing a present, which is a crummy role to have to take. But in the long term it’s better to be a full economic participant rather than a half participant. In the long term you and your descendants will be better off, much better off, if you are a true earner and customer rather than fodder for manipulation by digital networks.

Even if you think you really can’t get past this point, please just try a little longer. I think you’ll see that the benefits outweigh the costs.

One way to think about the third way I am proposing, the humanistic computing path, is that it is a “cyber-Keynesian” scenario of kicking cloud-computing schemes up onto a higher peak in an energy landscape.

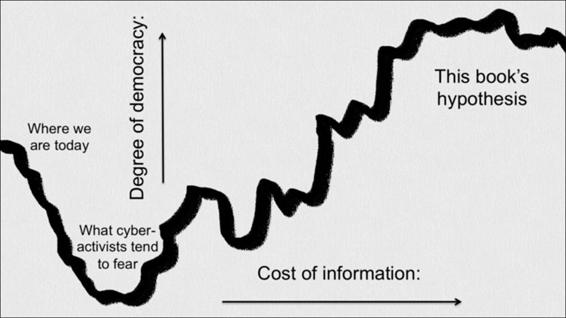

Recall the graphs of energy landscapes. We can draw various pictures of the central hypothesis of this book as such a landscape. In the picture below, I’ve labeled one of the axes vaguely as “degree of democracy,” since that’s one of the primary concerns that confuse discussions about monetizing information. (An illustration might have instead a Y-axis labeled “accessibility of material dignity.”)

At any rate, however one defines democracy, or if democracy is even a concern, the core hypothesis of this book is that there are higher peaks, meaning more intense, higher-energy digital economies to be found. Of course, if that is true, it also means there are more valleys, as yet undiscovered and unarticulated, to be avoided.

Cyber-Panglossian fallacies rule Silicon Valley conversations. The very idea that demonetized information might not mean the most possible freedom meets resistance in the current climate. I defy convention when I draw the vague “degree of democracy” as being only halfway up to its potential when the cost of information is zero.

This reminds me of the way some libertarians are convinced that lower taxes will

always

guarantee a wealthier society. The math is wrong; outcomes from complex systems are actually filled with peaks and valleys.

It’s an article of faith in cyber-democracy circles that making information more “free,” in the sense of making it copyable, will also lead to the most democratic, open world. I suspect this is not so. I have already pointed out some of the problems. A world that is open on the surface becomes more closed on a deeper level. You don’t get to know what correlations have been calculated about you by Google, Facebook, an insurance company, or a financial entity, and that’s the kind of data that influences your life the most in a networked world.

*

*

There are other problems that I explored more in my previous book. For instance, you also lose an ability to choose the context in which you express yourself, since more and more expression is channeled through Siren Servers, and that lessens your ability to express and explore unique perspectives.

A world in which more and more is monetized, instead of less and less, could lead to a middle-class-oriented information economy, in which information isn’t free, but is affordable. Instead of making information inaccessible, that would lead to a situation in which the most critical information becomes accessible for the first time. You’d own the raw information about you that can sway your life. There is no such thing as a perfect system, but the hypothesis on offer is that this could lead to a more democratic outcome than does the cheap illusion of “free” information.

We cannot hope to design an ideal network that will perfect politics; neither can we plan to replace politics with a perfect kind of commerce. Politics and commerce will both be flawed so long as people are free and experimenting with the future. The best we can aim for are network designs that focus politics and commerce to approximately balance each other’s flaws.

SIXTH INTERLUDE

The Pocket Protector in the Saffron Robe

THE MOST ANCIENT MARKETING

Are Siren Servers an inevitable, abstract effect that would consistently reappear in distant alien civilizations when they develop their own information networks? Or is the pattern mostly a function of distinctly human qualities? This is unknown, of course, but I suspect human nature plays a huge role. One piece of evidence is that those who are the most successful at the Siren Server game are also playing much older games at the same time.

Before Apple, for instance, Steve Jobs famously went to India with his college friend Dan Kottke. While I never had occasion to talk to Jobs about it, I did hear many a tale from Kottke, and I have a theory I wish I’d had a chance to try out on Jobs.

Jobs used to love the Beatles and bring them up fairly often, so I’ll use some Beatles references. When John Lennon was a boy, he once recalled, he saw Elvis in a movie and suddenly thought, “I want that job!” The theory is that Jobs saw gurus in India, focal points of love and respect, surrounded by devotees, and he similarly thought, “I want that job!”

This observation is not meant as a criticism, and certainly not as an insult. It simply provides an explanatory framework for what made Jobs a unique figure.

For instance, he liberally used the guru’s trick of treating certain devotees badly from time to time as a way of making them more devoted. This is something I heard members of the original Macintosh team confess, and they were tangibly stunned by it, over and over. They saw it being done to themselves in real time, and yet they consented. Jobs would scold and humiliate people and somehow elicit an ever more intense determination to win his approval, or more precisely, his pleasure.