When Do Fish Sleep? (27 page)

Sunbeam has long produced the 20030 toaster, an elegant two-slicer that selects the proper brownness of the bread by a radiant control that “reads” the surface of the bread to determine the degree of doneness. As far as we know, the Sunbeam 20030 is the only toaster that doesn’t work on a time principle. The 20030 actually measures the surface temperature of the bread by determining its moisture level and can accurately measure the time needed to toast any type of bread. Wayne R. Smith, of Sunbeam Public Relations, told

Imponderables

, “There’s no point in having radiant controls in both slots when having a control in one slot works just as well.”

Submitted by Lisa M. Giordano of Tenafly, New Jersey. Thanks also to Muriel S. Marschke of Katonah, New York; and Jim Francis of Seattle, Washington

.

Why

Are Almost All Cameras Black?

Black isn’t the most obvious color we would pick for cameras. Not only is black an austere and a threateningly high-tech color to amateurs, it would seem to have a practical disadvantage. As Jim Zuckerman, of Associated Photographers International, explained, black tends to absorb heat more than lighter colors, and heat is the enemy of film.

Of course, there was and is no reason why the exteriors of cameras need to be black. For a while, chromium finishes were popular on 35 millimeter cameras, but professional photographers put black tape over the finish to kill any possible reflections. Sure, some companies now market inexpensive cameras with decorator colors on the exterior. Truth be told, the persistence of black exteriors on cameras has more to do with marketing than anything else. As Tom Dufficy, of the National Association of Photographic Manufacturers, told us: “To the public, black equals professional.”

Submitted by Herbert Kraut of Forest Hills, New York

.

Why

Is There a Permanent Press Setting on Irons?

We buy a permanent press shirt so that we won’t have to iron it. Then after we wash the shirt for the first time, it comes out of the dryer with wrinkles. Disgusted, we pull out our iron only to find that it has a permanent-press setting. Are iron manufacturers bribing clothiers to renege on their promises? Is this a Communist plot?

The appliance industry is evidently willing to acknowledge what the clothing industry is reluctant to admit: A garment is usually permanently pressed only until you’ve worn it—once. Wayne R.Smith, consultant in Public Relations to the Sunbeam Appliance Company, suggested that “permanent press” was chosen to describe the benefits of some synthetic materials because “it has a far more attractive sound to consumers than ‘wrinkle-resistant.’”

We know what Mr. Smith means. We’ve always felt that the difference between a water-resistant watch and a waterproof watch was that the waterproof one would die the moment

after

it hit H

2

O.

What

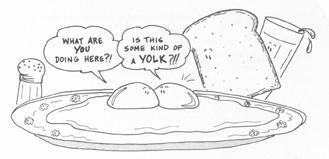

Causes Double-Yolk Eggs? Why Do Egg Yolks Sometimes Have Red Spots on Them?

Female chicks are born with a fully formed ovary containing several thousand tiny ova, which form in a cluster like grapes. A follicle-stimulating hormone in the bloodstream develops these ova, which will eventually become egg yolks. When the ova are ripe, the follicle ruptures and an ovum is released. Usually when a chicken ovulates, one yolk at a time is released and travels down the oviduct, where it will acquire a surrounding white membrane and shell.

But occasionally two yolks are released at the same time. Double-yolk eggs are no more planned than human twins. But some chickens are more likely to lay double-yolk eggs. Very young and very old chickens are most likely to lay double yolks; young ones because they don’t have their laying cycles synchronized, and old ones because, generally speaking, the older the chicken, the larger the egg she will lay. And for some reason, extra-large and jumbo eggs are most subject to double yolks.

If a chicken is startled during egg formation, small blood vessels in the wall may rupture, producing in the yolk blood spots—tiny flecks of blood. Most eggs with blood spots are removed when eggs are graded, although they are perfectly safe to eat.

Submitted by Lewis Conn of San Jose, California. Thanks also to Melody L. Love of Denver, North Carolina

.

We first encountered this Imponderable when a listener of Jim Eason’s marvelous KGO-San Francisco radio show posed it. “Ummmmm,” we stuttered.

Soon we were bombarded with theories. One caller insisted that red absorbed heat well, certainly an advantage when barns had no heating system. Talk-show host and guest agreed it made some sense, but didn’t quite buy it. Wouldn’t other colors absorb more heat? Why didn’t they paint barns black instead?

Then letters from the Bay area started coming in. Donna Nadimi theorized that cows had trouble discriminating between different colors and just as a bull notices the matador’s cape, so a red barn attracts the notice of cows. She added: “I come from West Virginia and once asked a farmer this question. He told me that cows aren’t very smart, and because the color red stands out to them, it helps them find their way home.” The problem with this theory is that bulls are color-blind. It is the movement of the cape, not the color, that provokes them.

Another writer suggested that red would be more visible to owners, as well as animals, in a snowstorm. Plausible, but a stretch.

Another Jim Eason fan, Kemper “K.C.” Stone, had some “suspicions” about an answer. Actually, he was right on the mark:

The fact is that red pigment is cheap and readily available from natural sources. Iron oxide—rust—is what makes brick clay the color that it is. That’s the shade of red that we westerners are accustomed to—the rusty red we use to stain our redwood decks. It’s obviously fairly stable too, since rust can’t rust and ain’t likely to fade.

The combination of cheapness and easy availability made red an almost inevitable choice. Shari Hiller, a color specialist at the Sherwin-Williams Company, says that many modern barns are painted a brighter red than in earlier times for aesthetic reasons. But aesthetics was not the first thing on the mind of farmers painting barns, as Ms. Hiller explains:

You may have noticed that older barns are the true “barn red.” It is a very earthy brownish-red color. Unlike some of the more vibrant reds of today that are chosen for their decorative value, true barn red was selected for cost and protection. When a barn was built, it was built to last. The time and expense of it was monumental to a farmer. This huge wooden structure needed to be protected as economically as possible. The least expensive paint pigments were those that came from the earth.

Farmers mixed their own paint from ingredients that were readily available, combining iron oxide with skim milk—did they call the shade “2% red”?—linseed oil and lime. Jerry Rafats, reference librarian at the National Agricultural Library, adds that white and colored hiding pigments are usually the most costly ingredients in paints.

K.C. speculated that white, the most popular color for buildings in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (see

Why Do Clocks Run Clockwise? and Other Imponderables

for more than you want to know about why most homes are and always have been painted white), was unacceptable to farmers because it required constant cleaning and touching up to retain its charm. And we’d like to think that just maybe the farmers got a kick out of having a red barn. As K.C. said, “Red is eye-catching and looks good, whether it’s on a barn, a fire truck, or a Corvette.”

Submitted by Kemper “K.C.” Stone of Sacramento, California. Thanks also to Donna Nadimi of El Sobrante, California; Jim Eason of San Francisco, California; Raymond Gohring of Pepper Pike, Ohio; Stephanie Snow of Webster, New York; and Bettina Nyman of Winnipeg, Manitoba.

On one momentous day we were sitting at home, pondering the imponderable, when the phone rang.

“Hello,” we said wittily.

“Hi. Are you the guy who answers stupid questions for a living?” asked the penetrating voice of a woman who later introduced herself as Helen Schwager, a friend of a friend.

“That’s our business, all right.”

“Then I have a stupid question for you. Why are manhole covers round?”

Much to Helen’s surprise, the issue of round manhole covers had never been important to us.

“Dunno.”

“Guess!” she challenged.

So we guessed. Our first theory was that a round shape roughly approximated the human form. And a circle big enough to allow a worker would take up less space than a rectangle.

“Nope,” said Helen, friend of our soon-to-be ex-friend. “Try again.”

Brainstorming, a second brilliant speculation passed our lips. “It’s round so they can roll the manhole cover. Try rolling a heavy rectangular or trapezoidal manhole cover on the street.”

“Be serious,” Helen insisted.

“O.K., we give up. Tell us, O brilliant Helen.

Why are manhole covers round?

”

“It’s obvious, isn’t it?” gloated Helen, virtually flooding with condescension. “If a manhole were a square or a rectangle, the cover could fall into the hole when turned diagonally on its edge.”

Helen, who was starting to get on our nerves just a tad, went on to regale us with the story of how she was presented with this Imponderable at a business meeting and came up with the answer on the spot. With tail between our legs, we got off the phone, mumbling something about maybe this Imponderable getting in the next book. First we get humiliated by this woman; then we have to give her a free book. Isn’t there any justice?

Of course, after disconnecting with Helen we did what any self-respecting American would do: We tortured our friends with this Imponderable, making them feel like pieces of dogmeat if they didn’t get the correct answer. And very few did.

Of course, we can’t rely on an answer provided by the supplier of an Imponderable, even one so intelligent as Helen, so we contacted many manufacturers of manhole covers, as well as city sewer departments.

Guess what? The manufacturers of manhole covers can’t agree on why manhole covers are round. Some, such as the Vulcan Foundry of Denham Springs, Louisiana, immediately confirmed Helen’s answer but couldn’t resist throwing a plug in as well (“Then, again, maybe manhole covers are round to facilitate the use of the Vulcan Classic Cover Collection”).

But the majority of the companies we spoke to said not only do manhole covers not have to be round but many aren’t. Manhole covers sit inside a frame or a ring that is laid into the concrete. Many of these frames cover the hole completely and are not hollow, so there is no way that a cover any shape could fall into the hole.

Most important, as Eric Butterfield, of Emhart Corporation, told

Imponderables

, manhole covers have a lip. Usually the man hole cover is at least one inch longer in diameter for each foot of the diameter of the hole.

Round manholes are more convenient in other ways. Lathe workers find circular products easier to manufacture. Seals tend to be tighter on round covers. And Lois Hertzman, of OPW, a division of Dover Corporation, adds that round manholes are easier to install because there are no edges to square off.

Everyone we spoke to mentioned that many manholes are not round. Many older manhole covers are rectangular. The American Petroleum Institute wants oil covers to be the shape of equilateral triangles (impractical on roadways, where this shape could lead to covers flipping over like tiddlywinks).