When Do Fish Sleep? (12 page)

Richard A. Anthes, director of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, offers another reason why we see so many buildings, and especially so many roofs, blown away during a hurricane. “Buildings offer a surface which provides a large aerodynamic lift, much as an airplane wing. This lift is often what causes the roof to literally be lifted off the building.”

We don’t want to leave the impression that trees can laugh off a hurricane. Many get uprooted and are stripped of their leaves. Often we get the wrong impression because photojournalists love to capture ironic shots of buildings torn asunder while Mother Nature, in the form of a solitary, untouched, majestic tree, stands triumphant alongside the carnage.

Submitted by Daniel Marcus of Watertown, Massachusetts

.

Why

Are Downhill Ski Poles Bent?

Unlike the slalom skier’s poles, which must make cuts in the snow to negotiate the gates, the main purpose of the downhill ski poles is to get the skier moving, into a tuck position…and then not get in the way.

According to Tim Ross, director of Coaches’ Education for the United States Ski Coaches Association, the bends allow the racer “to get in the most aerodynamic position possible. This is extremely important at the higher speeds of downhill.” Savings of hundredths of a second are serious business for competitive downhill skiers, even when they are attaining speeds of 60-75 miles per hour.

If the bends in the pole are not symmetrical, they are designed with careful consideration. Dave Hamilton, of the Professional Ski Instructors of America, reports that top-level ski racers have poles individually designed to fit their dimensions. Recreational skiers are now starting to bend their poles out of shape. According to Ross, the custom-made downhill ski poles may have as many as three to four different bend angles.

Funny. We haven’t seen downhill skiers with three to four different bend angles in their bodies.

Submitted by Roy Welland of New York, New York

.

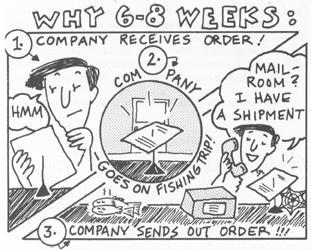

This is a mystery we have pondered over ourselves, especially since these same companies that warn us of six-to-eight-week delivery schedules usually send us our goods within a few weeks. We talked to several experts in the mail-order field who assured us that any reasonably efficient operation should be able to ship items to customers within two to three weeks.

Many manufacturers farm out much or all of the processing of mail orders to specialized companies, called fulfillment houses. Some fulfillment houses do everything from receiving the initial letters from customers and obtaining the proper goods from their own warehouses to producing address labels, maintaining inventory control, and shipping out the package back to the customer.

Dick Levinson, of the fulfillment company H.Y. Aids Group, told

Imponderables

that a fulfillment house should be able to gurarantee a client a turnaround of no more than five days from when a check is received until the package is shipped to the customer. A two-or three-day turnaround is the norm.

Do the mail order companies blame the post office? Why not? Everybody else does. But despite a few carpings, all agreed that even third-class packages tend to get delivered anywhere in the continental United States within a week.

Being paranoid types, we thought about a few nefarious reasons why mail-order companies might want to delay orders. Perhaps they want to create a little extra cash flow by holding on to checks for an extra month or so? No, insisted all of our sources.

How about advertising goods they don’t have in stock? As checks clear, companies could pay for their inventory out of customer money rather than their own. It’s possible but unlikely, said our panel. Stanley J. Fenvessey, founder of Fenvessey Consulting and perhaps the foremost expert on fulfillment, said that only a fly-by-night operation would try to get away with such shenanigans. He offered a few more benign explanations.

Sometimes a mail-order company, particularly one that specializes in imports or seasonal items, might run out of stock temporarily. By listing a delayed delivery date, the company forestalls complaints, even though it expects to deliver merchandise in half the stated time.

And in the magazine field, fledgling efforts sometimes try a “dry test,” in which prospective subscribers are solicited by mail even though no magazine yet exists. Only if there is a high enough response rate will the magazine ever be produced.

The most compelling reason is the Federal Trade Commission’s Mail Order Rule. The rule was established in 1974 after consumers complained in droves about late or nonexistent shipments of merchandise by mail-order operations. The President’s Office of Consumer Affairs reported that the number of complaints registered against mail-order firms was second only to complaints about automobiles and auto services.

The Mail Order Rule states that a buyer has the right to assume that goods will be shipped within the time specified in a solicitation and, “if no time period is clearly and conspicuously stated, within thirty days after receipt of a properly completed order from the buyer.” Furthermore, when a seller is unable to ship merchandise within the time provisions of the rule, the seller must not only notify the buyer of the delay but also offer the option to the buyer to cancel the order.

Refunding money is not exactly any company’s favorite thing to do, but the provisions about sending the notice of delay and option to cancel is perhaps more onerous to mail-order firms. Not only must the seller spend money on mailing these notices, but must somehow track the progress of each order to make sure it hasn’t exceeded the 30-day limit. The bookkeeping burden is enormous.

Finally, we have arrived at the answer: By putting a shipping deadline of much longer than they think they will ever need, mail-order firms avoid having to comply with the provisions of the thirty-day rule whenever they run out of stock temporarily.

But don’t these disclaimers discourage sales? After all, most items ordered by mail are available in retail stores as well. Dick Levinson suggests that most items ordered from magazines and newspapers are impulse items rather than necessities, and that most buyers are flexible about delivery schedules. Lynn Hamlin, book buyer for New York’s NSI Syndications Inc., commented that space customers (those who order from newspapers and magazines) are less demanding than those who order from catalogs with toll-free phone numbers and who have the ability to ask a company operator how long the delivery will take. NSI advertisements guarantee shipment within 60 days, but usually are filled in two or three weeks. Ms. Hamlin notes that she has not seen any detrimental effect of the sixty-day guarantee on her company’s sales, although she admits that around December 1, some potential customers might fear whether merchandise would arrive by Christmas.

Stanley Fenvessey informs us that about 75 to 90% of all catalog merchandise is delivered within two weeks, and insists that no large catalog house would ever print “six to eight weeks for delivery.” One of Fenvessey’s smaller clients, who owned a catalog company, printed “please allow four to five weeks for delivery” on his catalog. Fenvessey asked his client whether it really took this long to fulfill orders. The client replied that most orders were delivered in two weeks.

“So why put four to five weeks in the catalog?” asked Fenvessey.

“Because this way we avoid hassles when we are a few days late.”

Fenvessey was convinced that the client couldn’t see the forest for the trees. Fenvessey conducted a test in which two sets of catalogs were printed and shipped; the only difference between the two was that one announced that delivery would be between two to three weeks; the other, four to five weeks. The two to three week catalog drew 25% more orders, a huge difference.

Maybe many space advertisers are losing sales by scaring potential customers into thinking they’re going to have to wait longer than they really will to get merchandise.

Submitted by Susie T. Kowalski of Middlefield, Ohio

.

The poser of this Imponderable, Susan Diffenderffer, insisted she had the correct answer in hand: “In a square silo, grain could form an air pocket and cause spontaneous combustion. There are no corners in a round silo.”

Well, we think the spontaneous combustion theory is a tad apocalyptical, but you have the rest of the story right. Actually, at one time silos were square or rectangular. Fred Hatch, a farmer from Illinois, built a square wooden silo in 1873. But the square corners didn’t allow Hatch to pack the silo tightly enough. As a result, air got in the silo and spoiled much of the feed. To the rescue came Wisconsin agricultural scientist, Franklin H. King, who built a round silo ten years later. The rest is silage history.

Why is it so important to shut air out of a silo? The mold that spoils grain cannot survive without air. Without air, the grass and corn actually ferment while in the silo, inducing a chemical change in the silage that makes it palatable all through the winter season.

Before silos were invented, cows gave less milk during winter because they had no green grass to eat. Silos gave the cows the lavish opportunity to eat sorghums all year long.

Submitted by Susan C. Diffenderffer of Cockeysville, Maryland

.

For many years we’ve been looking at want ads in the newspaper and seeing positions open for PBX operators. We’ve always wondered what the heck they did. “PBX” sure sounds threateningly high-tech. Little did we know that we were already experts in the field.

PBX systems are simply telephone lines designed for communication within one building or business that are also capable of interfacing with the outside world. Most large hotels have a PBX system. When you lift your phone up in your room, you become a PBX station user whether you like it or not.

Most PBX systems reserve numbers one through seven for dial access to other internal PBX stations. In a hotel, this allows a guest in one room to call another room directly. Decades ago, one might have dialed for the operator to perform this function, but hotels found that patrons preferred the greater speed of direct access; and of course, direct dialing saved hotels the labor costs of operators.

There is no inherent reason why 4 or 2

couldn’t

be the access code for an outside line or long-distance access, but Victor J. Toth, representing the Multi-Tenant Telecommunications Association, explains how the current practice began:

The level “9” code is usually used by convention in all commercial PBX and Centrex as the dialing code for reaching an outside line. This number was chosen because it was usually high enough in the number sequence so as not to interfere with a set of assigned station numbers (or, in the case of a hotel, a room number).

Likewise, the 8 is sufficiently high in the number sequence to not interfere with other station numbers and has become the conventional way to gain access to long-distance services.

Toth adds that it is easy to deny level 9 class of service to a particular phone or set of phones if desired. Most hotels, for example, make it impossible for someone using a lobby phone to dial outside the hotel, let alone long distance.