When Do Fish Sleep? (9 page)

For those having similar problems with twisted lines connecting their phones to the modular jacks in the wall, simply unplug the line from the phone. If the line is sufficiently coiled, it will untwist like an untethered garden hose.

Submitted by Alan B. Heppel of West Hollywood, California

.

Why

Do Golf Balls Have Dimples?

Because dimples are cute?

No. We should have known better than to think that golfers, who freely wear orange pants in public, would worry about cosmetic appearances.

Golf balls have dimples because in 1908 a man named Taylor patented this cover design. Dimples provide greater aerodynamic lift and consistency of flight than a smooth ball. Jacque Hetric, director of Public Relations at Spalding, notes that the dimple pattern, regardless of where the ball is hit, provides a consistent rotation of the ball after it is struck.

Janet Seagle, librarian and museum curator of the United States Golf Association, says that other types of patterned covers were also used at one time. One was called a “mesh,” another the “bramble.” Although all three were once commercially available, “the superiority of the dimpled cover in flight made it the dominant cover design.”

Although golfers love to feign that they are interested in accuracy, they lust after power: Dimpled golf balls travel farther as well as straighter than smooth balls. So those cute little dimples will stay in place until somebody builds a better mousetrap.

Submitted by Kathy Cripe of South Bend, Indiana

.

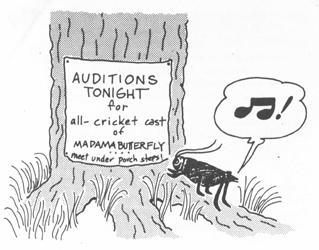

If we rubbed our legs together for five minutes as vigorously as crickets do all the time, our legs would turn beet red and we would hobble into the bathroom searching for the talcum powder. How do crickets survive?

Quite well, it turns out. For it turns out that we can’t believe everything we learned in school. Crickets don’t chirp by rubbing their legs together. Entomologist Clifford Dennis explains:

Crickets do not produce chirps by rubbing their legs together. They have on each front wing a sharp edge, the scraper, and a file-like ridge, the file. They chirp by elevating the front wings and moving them so that the scraper of one wing rubs on the file of the other wing, giving a pulse, the chirp, generally on the closing stroke.

On a big male cricket, the scraper and the file can often be seen by the naked eye. You can take the wings of a cricket in your fingers and make the chirp sound yourself.

No thanks. We’ll take your word for it on faith.

Submitted by Sandra Baxter of Ada, Oklahoma

.

Why

Is a Navy Captain a Much Higher Rank than an Army Captain? Has This Always Been So?

When one looks at the ranks of the officers of the four branches of the American military, one is struck by how the Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps use the identical ranks, while the Navy uses different names for the equivalents. But there is one striking disparity: the Navy elevates the rank of captain.

Army, Air Force, | Navy |

Warrant Officer | Warrant Officer |

Chief Warrant Officer | Chief Warrant Officer |

Second Lieutenant | Ensign |

First Lieutenant | Lieutenant Junior Grade |

CAPTAIN | Lieutenant |

Major | Lieutenant Commander |

Lieutenant Colonel | Commander |

Colonel | CAPTAIN |

Brigadier General | Commodore |

Major General | Rear Admiral |

Lieutenant General | Vice Admiral |

General | Admiral |

General of the Army or General of the Air Force | Fleet Admiral |

The word “captain” comes from the Latin word

caput

, meaning “head.” In the tenth century, captains led groups of Italian foot soldiers. By the eleventh century, British captains commanded warships. So the European tradition has been to name the head of a military unit of any size, on land or sea, a captain.

Our elevation of the English captain stems from English naval practice. In the eleventh century, British captains were not the heads of ships

per se

. Although captains were in charge of leading soldiers in combat aboard ship, the actual responsibility for the navigation and maintenance of ships fell upon the ranks of master. By the fifteenth century, captains bristled at deferring to the masters they outranked, and captains began to assume the responsibility for the ships heretofore claimed by masters. By 1747 any commander of a ship was officially given the rank of captain.

Meanwhile, on land most European countries named the commander of a company—of any size—captain. By the sixteenth century, military strategists felt that one hundred to two hundred men were the maximum size for a land unit in battle to be effectively led by one person. That leader was known as a captain.

From the inception of the United States military we borrowed from the European tradition. A captain was a company commander and indeed is so today. In the Air Force, a captain commands a squadron, the airborne equivalent of a company. But the Navy captain, because he has domain over such a big and complicated piece of equipment, has a legitimate claim to a higher rank than his compatriots in the other branches. As Dr. Regis A. Courtemanche, of the Scipio Society of Naval and Military History, put it,

Navy captain isn’t only a rank. The senior officer of a ship is always called “Captain” even though his rank may only be lieutenant. So a naval captain may have more responsibility than a military captain who usually commands only a small detachment in battle.

In 1862, the Navy realized that it was no longer practical to make captain its highest rank. They needed a way not only to differentiate among commanders of variously sized and equipped vessels but to reward those who were supervising the captains of warships. For this reason, the Navy split the rank of captain into three different categories. The commodore (and later, the rear admiral) became the highest grade, the commander the lowest, and the captain, once ruler of the seas, stuck in the middle of the ranks.

Submitted by Barrie Creedon of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

.

Merry Wooten, of the Astronomical League, informs us that most early telescopes didn’t yield upside-down images. Galileo’s original spyglass used a negative lens as an eyepiece, just as cheap field glasses made with plastic lenses do now. So why do unsophisticated binoculars yield the “proper” image and expensive astronomical telescopes render an “incorrect” one?

Astronomy

editor Jeff Kanipe explains:

The curved light-gathering lens of a telescope bends, or refracts, the light to focus so that light rays that pass through the top of the lens are bent toward the bottom and rays that pass through the bottom of the lens are bent toward the top. The image thus forms upside down and reversed at the focal point, where an eyepiece enlarges the inverted and reversed image.

Alan MacRobert, of

Sky

&

Telescope

magazine, adds that some telescopes turn the image upside down, and others also mirror-reverse it: “An upside-down ‘correct’ image can be viewed correctly just by inverting your head. But a mirror image does not become correct no matter how you may twist and turn to look at it.”

O.K. Fine. We could understand why astronomers live with inverted and upside-down images if they had to, but they don’t. Terrestrial telescopes do rearrange their image. Merry Wooten says that terrestrial telescopes can correct their image by using porro prisms, roof prisms, or most frequently, an erector lens assembly, which is placed in front of the eyepiece to create an erect image.

Why don’t astronomical telescopes use erector lenses? For the answer, we return to Jeff Kanipe:

Most astronomical objects are very faint, which is why telescopes with larger apertures are constantly being proposed: Large lenses and mirrors gather more light than small ones. Astronomers need every scrap of light they can get, and it is for this reason that the image orientation of astronomical telescopes are not corrected. Each glass surface the light ray encounters reflects or absorbs about four percent of the total incoming light. Thus if the light ray encounters four glass components, about sixteen percent of the light is lost. This is a significant amount when you’re talking about gathering the precious photons of objects that are thousands of times fainter than the human eye can detect. Introducing an erector into the optical system, though it would terrestrially orient the image, would waste light. We can afford to be wasteful when looking at bright objects on the earth but not at distant, faint galaxies in the universe.

And even if the lost light and added expense of erector prisms weren’t a factor, every astronomer we contacted was quick to mention an important point: There IS no up or down in outer space.

Submitted by William Debuvitz of Bernardsville, New Jersey

.

We won’t even comment on the

taste

of airline food (this is a family book). But if McDonald’s can separate the cold from the hot on a McDLT sandwich, why can’t the airlines get their rolls within about 50 degrees of the right temperature?

The answer lies in how airline meals are prepared aloft. The salad, bread, and dessert are placed on trays that are usually refrigerated or packed in ice. Entrees are loaded onto separate baking sheets. When it is time to start the meal service, the flight attendant who prepares the meals simply sticks the trays of entrees into ovens (not, by the way, microwaves).

The rolls are cold because they have been sitting all along with the salad and cake. Most airlines offer customers a choice of entrees. The flight attendant who is serving the meal simply selects the entree from the sheets they were cooked in and places it alongside the rest of the meal. Except for the entree choice, every flier’s tray will look identical. Note that although most airlines vary the vegetable according to the entree, the vegetable is always cooked on the same plate as the main course because the entree plate will be the only heated element on the tray.

If the bread and salad taste cold, why doesn’t the dessert? Airlines, almost without exception, serve cake for dessert. Michael Marchant, vice president of Ogden Allied Aviation Services and the president of the Inflight Food Service Association, told

Imponderables

that the softness of cake fools us into thinking it is being served at room temperature. The gustatory illusion is maintained because in contrast to the roll’s hard crust, which locks in the coldness, the soft frosting of a cake dissipates the cold.