When Computers Were Human (44 page)

Read When Computers Were Human Online

Authors: David Alan Grier

With the emergence of Archibald and MTAC, Comrie and the Scientific Computing Service, Davis and his books on mathematical functions, Blanch and Lowan and the Mathematical Tables Project, human computers began to claim that they had an independent discipline, that they commanded a body of knowledge that stood apart from astronomy, mathematics, and statistics. This was not a philosophical question but a practical issue with practical consequences. If computing was an independent body of knowledge, then it should have a standard way of training new computers, a publication to disseminate new ideas, and an organization that could coordinate research. “If it be proposed to advance some truth, or to foster some feeling by the encouragement of a great example,” wrote Alexis de Tocqueville, “[Americans] form a society.”

29

In 1939, MTAC appeared to be the germ of a new computing society, but before it could claim such a role, Archibald would have to gain the support and confidence of the major computing organizations. His work was complicated by the emergence of the new computing machines and by the start of a new world war, which promised far more work for human computers than had ever been found by Oswald Veblen and his friends in the summer of 1918.

September 1939 brought a new urgency to America's scientific and industrial research. On the third day of the month, Germany ended the armistice of 1918 by invading Poland. Great Britain rushed to the aid of the Poles, and France followed. In increasing numbers, Americans believed that they would be drawn into the war, but this time they were not rushing into the fray. They had seen enough of battle during those brief months in 1918, when the American Expeditionary Force had fought on the western front.

30

Following the invasion, President Franklin Roosevelt

had to remind the country that “though we may desire detachment, we are forced to realize that every word that comes through the air, every ship that sails the sea, every battle that is fought, does affect the American future.”

31

The scientific veterans of the First World War volunteered for a second round of military research. Having watched the army take control of the National Research Council in 1917, they formed a new coordinating committee that included the interests of both the army and the navy but kept the balance of power in the hands of civilian scientists. This organization, the National Defense Research Committee, divided its work among broad alphabetic classes of military needs. The committee had a Division A for armor and ordnance, B for bombs and explosives, C for communications, D for detection devices and controls. To these four sections was added a fifth, Division E, that dealt with the rights of the inventors. There was no division M for mathematics and computation, as such research did not seem to be a high priority, even though both military services moved to strengthen their existing computing laboratories. The army invested $800,000 in the Aberdeen Ballistics Research Laboratory, using part of those funds to expand the computing laboratory.

32

The navy, which had just retired the director of its Nautical Almanac Office, went in search of a leader who understood computing machinery.

The almanac had seen little change since the retirement of Simon Newcomb, some forty years before. In Simon Newcomb's last years, the navy had closed the almanac office in Foggy Bottom and moved the computers to the new Naval Observatory, which overlooked the monuments and government offices from atop St. Alban's Hill. Since that time, the group had been overseen by a sequence of dependable but unimaginative directors. A review by the naval officers remarked that almanac directors of the early twentieth century “did see to it that the Almanacs were produced on time,” but they had done nothing to advance the capabilities of the office.

33

Using blunter language, L. J. Comrie concluded that the computing laboratory was “stagnant.”

34

Under either judgment, the almanac was unprepared to handle the work that came with the start of hostilities. For nearly thirty years, the American almanac staff had shared the burden of ephemeris computations with the almanac offices of England, France, Germany, Russia, and Spain.

35

This collaboration had begun in 1912, when the United States had officially abandoned the prime meridian in Washington. It had been suspended for the First World War and been resumed in the 1920s. Now, for the second time in twenty years, the almanac staff found that they were computing the tables for the

Nautical Almanac

without the full assistance of its European collaborators. Germany withdrew from the agreement to share almanac computations, and France found itself unable to contribute its part. As the staff struggled

with additional work, naval officers were designing a new almanac for airplane navigators. This almanac would be exceptionally detailed, as airplane navigators needed astronomical positions at fifteen-minute intervals. Without this kind of detail, navigational computations would forever lag behind the actual position of the plane by a distance of 10 or 50 or even 200 miles.

36

There were many senior astronomers and mathematicians who were qualified to lead the almanac office and at least a few who were ambitious to fill the role, but the navy wanted only one individual, Wallace Eckert of the Thomas J. Watson Astronomical Computing Bureau, as the Columbia University computing facility was now called. Eckert was flattered by the initial overture but was not especially interested in the position. He was happy in New York and saw no reason to leave. The superintendent of the Naval Observatory, unwilling to accept Eckert's refusal, persisted in his efforts to entice the Columbia astronomer to Washington. He appealed to Eckert's patriotism, suggested that Eckert would have more influence in the national capital than in New York, and openly flattered Eckert with the notion that he “would go down in history as a second Newcomb.” In a moment of emotional vulnerability that seemed out of place for a naval officer, the superintendent confessed, “I have never wished for anything so hard in my life as that you will accept the position and come to Washington.”

37

Eckert finally accepted the position in the spring of 1940. He left the

Columbia Astronomical Computing Bureau in the hands of an assistant and moved to Washington. He arrived at the almanac intending to install IBM equipment in the office and teach the computers the methods that he had developed in New York, but as he settled into his new office, Eckert discovered that he would not have the same kind of resources Columbia University received from Thomas Watson and IBM. With dismay, he reported, “The funds available for punched card equipment were sufficient to form the nucleus of a scientific computing laboratory for part of the year only.” But Eckert was not a blind partisan of punched card technology, and he knew that there were other ways of producing an almanac, ways that might even prove to be less expensive than the leases for IBM equipment. Borrowing an idea from L. J. Comrie, Eckert adapted a Burroughs accounting machine to act as a difference engine. Once the staff had prepared the initial values for an astronomical table, the accounting machine could compute the rest. Though the Burroughs machine was not intended for scientific calculations, it proved sufficient to the task at hand. By the end of Eckert's first year in Washington, he could report that “the work of the office as a whole has been advanced two or three months,” even though he did not have the equipment or the staff that he desired.

38

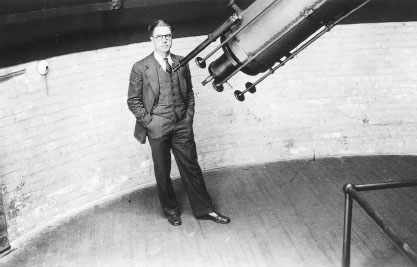

37. Wallace Eckert

In June 1940, the Mathematical Tables Project stood as the largest scientific computing organization in the United States, dwarfing the combined staff of the Aberdeen Proving Ground, the American

Nautical Almanac

, the Thomas J. Watson Astronomical Computing Bureau, and the mathematics division of Bell Telephone Laboratories. The WPA computing floor was home to three hundred computers. Half of this group still computed with paper and pencil; the remainder pulled the cranks of old adding machines.

39

Another hundred workers checked results, did preparatory calculations, and edited the finished numbers. The group had published six volumes of tables and an equal number of scholarly articles. The planning committee was working on ten volumes more.

40

Yet the project remained on the fringe of the scientific community. Arnold Lowan could not begin his day, could not open his mail, could not talk with his workers without being reminded that he was running a work relief effort. The WPA dictated the hours he worked, the problems he could undertake, and the laborers he could hire. The label of work relief stuck to him like the dirt of the streets, and no matter how hard he stamped his feet, he could not shake the dust from his boots. “The first requisite of a satisfactory organization of science for war is that it must attract first-rate scientists,” wrote the historian James Phinney Baxter. “One outstanding man will succeed where ten mediocrities will simply fumble.”

41

As the country prepared for war, as R. C. Archibald brought direction and discipline

to the Subcommittee on Bibliography of Mathematical Tables and Other Aids to Computation, and as Wallace Eckert acquired difference engines and punched card equipment for the

Nautical Almanac

staff, Lowan felt a constant pressure to show that his project held at least a few first-rate minds and was not a collection of three hundred unemployable mediocrities.

38. Mathematical Tables Project computers with adding machines

Nothing symbolized professionalism more than the presence of computing equipment, be that equipment punched card tabulators, electric desk calculators, or even the weary Sunstrands. WPA officials were unwilling to grant more machines to the project, even though Arnold Lowan argued that machine-driven calculators would allow him to hire more handicapped workers. A “one armed operator using the new Frieden calculator was able to produce 40% more work than an unimpaired worker using a calculator which is not fully automatic,” read one of his proposals.

42

WPA officials responded by asking, “Which important tables will have to be abandoned if it is impossible to secure machines?” and then summarily declining the request.

43

Lowan was more successful in raising money and acquiring machines when he discovered that he could look beyond the WPA office. Sometime in late 1940 or early 1941, he realized that the Mathematical Tables Project was legally an independent organization that could solicit contracts

from any institution, including the project sponsor, the National Bureau of Standards, and the other offices of the United States government. Sensing that there might be an opportunity to do some work for the military, Lowan offered the services of the Mathematical Tables Project to both the army and the navy. He was at first surprised, but ultimately pleased, to discover that both branches of the military employed large computing organizations to support surveyors and the construction of maps.

44

In the spring of 1941, the army offered Lowan a contract to handle the most repetitious of survey calculations, the preparation of map grids. Map grids reconciled the local geometry of left and right, north and south, with the curvature of the earth. They were particularly useful for field commanders when they looked for sites to place artillery batteries or sought ways to march troops across unmarked land. The army needed such grids for areas that were vulnerable to attackâAlaska, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and the Caribbean basinâand they were willing to make the Mathematical Tables Project a generous offer if it could do the work quickly. The contract included funds for the purchase of new electrical adding machines and the lease of IBM tabulators. “We greatly appreciate your cooperation in providing this equipment,” wrote Lyman Briggs, who had to approve the final contract. He added that the calculations for the map grids would be “undertaken as soon as the necessary IBM equipment can be obtained.”

45