Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College (40 page)

Read Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College Online

Authors: Sandra Aamodt,Sam Wang

Tags: #Pediatrics, #Science, #Medical, #General, #Child Development, #Family & Relationships

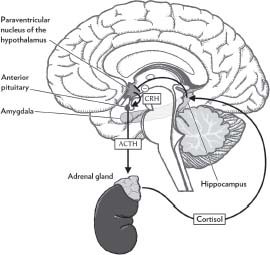

An effective stress response starts quickly and ends quickly. Binding of glucocorticoids to receptors in the hippocampus activates a negative feedback loop that shuts down CRH release and thus halts glucocorticoid production. This is important because if glucocorticoid levels stay high for a long time, you can end up with a number of ailments, including high blood pressure, damaged immune system function, osteoporosis, insulin resistance, or heart disease.

Chronically elevated glucocorticoids can also lead to brain problems. They may inhibit the birth of new neurons, disrupt neural plasticity, kill neurons in the hippocampus, or cause structural changes in the amygdala. Chronic stress makes fear conditioning easier and its extinction more difficult. Over time, the hippocampal damage not only impairs learning but also reduces the brain’s ability to terminate the stress response, initiating a cycle of problems that lead to more hippocampal damage. Finally, stress causes dendrites in the prefrontal cortex to atrophy and disrupts executive function (see

chapter 13

).

These two systems interact extensively with each other. Neurons that produce CRH and influence stress responses are also found in the amygdala, the prefrontal, insular, and cingulate cortex, and other brain regions. The amygdala

neurons, for example, project to the

locus coeruleus

, which regulates the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. In turn, neurons in the locus coeruleus can increase production of CRH in the hypothalamus.

As parents help their young children to cope with stress, the quality of their support regulates the children’s HPA responses. Physiological stress responsiveness declines over the first year of life in normally developing children. They still cry to get help from their parents, but this type of crying is not accompanied by an HPA response. Toddlers and older children in secure attachment relationships show less elevation of cortisol in response to stress than children with insecure attachment relationships, those who do not see their parents as a reliable source of comfort (see

chapter 20

).

The strongest stress responses are found in children with disorganized attachment relationships, in which the parent often makes the child afraid, either through aggression toward the child or by being extremely anxious. Such children also have the highest risk of behavioral or emotional difficulties.

In all cases, as children become adolescents, they transition to adult patterns of stress responsiveness, becoming more vulnerable to stressful events. This may be related to the increased risk of psychopathology during those years (see

chapter 9

).

In most toddlers, crying is not accompanied by a stress hormone response.

The stressors that you can expect to encounter in life depend on the characteristics of your particular environment. In many mammalian species, babies’ brains prepare themselves for the type of world they’ll find when they grow up by tuning their stress-response systems based on their experiences during early life. This process is one of the best-understood examples of epigenetic modification, in which the environment permanently influences the way our genes are expressed and, ultimately, our long-term behavior (see

Did you know? Footprints on the genome

).

Stress profoundly affects the developing brain. In

chapter 2

(see

Practical tip: Less stress, fewer problems

), we wrote about the effects of prenatal stress, as studied in the pregnant Louisiana women who escaped from hurricane strike zones, as well as pregnant women who experienced other forms of severe stress

such as the death of a close relative. Babies born to these stressed mothers had a substantially increased risk of problems, including autism, schizophrenia, decreased IQ, and depression.

Broadly speaking, the effects of early life stress seem to be similar in people, rodents, and monkeys. Babies whose mothers were stressed or depressed during pregnancy show increased responsiveness (HPA activity) to stress later in life. Adults who were abused as children also respond to stress with stronger and more prolonged HPA and sympathetic nervous system activity than those who weren’t. Probably as a consequence, previously abused adults have smaller hippocampal volumes and an increased risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression and anxiety, schizophrenia, and drug abuse. Other brain structures are likely to be affected as well, though this is less well studied.

How does early experience tune the stress response? The relationships of rats and their pups can shed some light on the subject. In rat pups, maternal licking and grooming reduce physiological stress responses. Mother rats vary naturally in how much time they spend licking and grooming their pups during the first week of life, and there is evidence that rats are able to develop normally either way. But mothers who groom a lot raise pups that are less fearful as adults and whose HPA stress responses are smaller and don’t last as long, compared to animals raised by low-grooming mothers. Experiments where rat pups in one group were “adopted” by mothers from the other group confirm that this effect is due to environment, rather than genetics.

It’s tempting to think of high-grooming mothers as the “good” mothers, but that would be a misconception. Instead, both types of mothers are matching their pups’ adult behavior to local conditions, one of the key aims of neural development. Remember that not all stress responses are bad. Pups born into difficult circumstances may survive better if they are vigilant and their HPA system is reactive. If mothers who were high-grooming with their first litter of pups are stressed during their second pregnancy, they become low-grooming mothers for those pups and also for their third litter, meaning that their future offspring will have more reactive HPA systems.

Other indicators of a tough environment during gestation, such as protein deprivation or exposure to bacterial infection, also increase adult HPA responsiveness in rats. Not only that; pups who receive low levels of licking and grooming reach sexual maturity earlier and are more likely to become pregnant after a

single mating session than pups raised by high-grooming mothers. In a tough environment (see

chapter 30

), these benefits for survival and early reproduction may constitute a worthwhile trade-off for a higher risk of chronic diseases late in life.

Canadian researcher Michael Meaney and his colleagues traced the molecular and neural consequences of early licking and grooming in rats. These maternal behaviors trigger the release of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the pup’s hippocampus, where it initiates a series of intracellular signals that reduce the epigenetic silencing of glucocorticoid receptor genes (see

Did you know? Footprints on the genome

). Because this DNA modification is permanent, pups that receive a lot of grooming grow up to have high levels of glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus and thus can terminate stress responses effectively throughout life. They also grow up to be mothers who lick and groom their own pups a lot, thereby passing the epigenetic modification to the next generation. In rats reared by low-grooming mothers, treatment with a drug that removes methyl groups from DNA can reverse the heightened HPA stress responsiveness.

The HPA stress response in monkeys is also tuned by early experience. To mature normally, young rhesus monkeys (like children) need to form an attachment to at least one reliable adult, usually the mother. Monkeys who are raised in a peer group instead of by mothers (a situation that, in humans, would constitute criminal child neglect) show a variety of unusual behaviors. As young animals, they explore little and play less. As adults, they are fearful and aggressive in response to threats and have a strong HPA response to separation from their peer group.

This phenomenon is especially severe in monkeys that carry a particular variant of the serotonin transporter gene, also called 5-HTT, which is also reported to increase vulnerability in people. The serotonin transporter removes serotonin from the synapse after its release by neurons, terminating the neurotransmitter’s activity. Among primates, only people and rhesus monkeys show variation in this gene. Any given gene comes in different versions called

alleles

, which are part of normal genetic variation. Monkeys carrying the short allele of the serotonin transporter show higher HPA reactivity than animals with two copies of the long allele, but only when raised in a peer group. When raised by mothers, both types of monkeys have similar adult outcomes. Researchers conclude that variation in this gene contributes to behavioral flexibility in the population, which in turn allows rhesus monkeys—and people—to thrive in many different environments.

What determines individual stress responses in people? Recall from

chapter 4

that specific combinations of genetic and environmental factors can lead to certain outcomes when neither factor alone has an effect. These interactions are challenging to tease out because so many combinations are possible.

Children seem to develop their coping skills most effectively if they are exposed to a moderate amount of stress: high enough that they notice it, but low enough that they can handle it.

One major contributor to our understanding has been a longitudinal study that followed over one thousand children born between April 1972 and March 1973 in Dunedin, New Zealand, from age three into adulthood. In this study, Avshalom Caspi, Terrie Moffitt, and their colleagues identified several psychiatric examples of gene-environment interactions, in which an experience increases the risk of a certain outcome only in people who carry a particular gene variant.

The best-known finding of the Dunedin study is that the risk of depression following childhood maltreatment or stressful life events is higher in people with the short allele of the serotonin transporter gene (and higher still in people with two copies of the short allele). People with two copies of the long allele are most resilient, with a low risk of depression regardless of their childhood experience. In contrast, people with two copies of the short allele have a risk of depression that increases in proportion to the childhood abuse they’ve suffered. Severe maltreatment doubles the risk of depression in this group.

The Dunedin study uncovered two other dangerous gene-environment combinations. Childhood maltreatment is more likely to lead to antisocial behavior in people who carry an allele that leads to low activity of a variant of the enzyme

monoamine oxidase

. This enzyme degrades serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, all neurotransmitters involved in stress responding and mood regulation.

Also, heavy marijuana use during adolescence increases the risk of schizophrenia in people with a particular variant of the gene for

catechol-Omethyltransferase

. This enzyme breaks down the neurotransmitters dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. People who start using marijuana as adults do not have an increased risk of schizophrenia, regardless of genotype.

PRACTICAL TIP: DANDELION AND ORCHID CHILDREN

If certain genes make children more vulnerable to damage under stressful conditions, why do they persist in the population? Some researchers think it’s because children who are more sensitive to the environment may fare better in stable, supportive conditions—though conversely, difficult environments are harder on them. That is to say, we might replace the label

difficult children

with

orchid children

: they’re sensitive, but if raised well, the results can be great.

As we already mentioned, most children are dandelions; they flourish in any reasonable circumstances. In contrast, orchid children with difficult temperaments (quick to anger or fear) benefit measurably from supportive parenting (see

chapter 17

). The combination of difficult temperament and harsh or unreliable parenting is a strong predictor of delinquency and psychiatric problems in many studies.