Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College (26 page)

Read Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College Online

Authors: Sandra Aamodt,Sam Wang

Tags: #Pediatrics, #Science, #Medical, #General, #Child Development, #Family & Relationships

A basic principle of neuroscience is that brains become better at doing whatever they do frequently. Video game players are an excellent illustration of this point, as they typically invest hundreds or thousands of hours into practicing games that require the rapid detection of targets and their discrimination from nontarget distractors. Daphne Bavelier and her colleagues showed that this effort improves response speed (across a variety of tasks) and visual attention abilities of players’ brains. Although you might imagine that video games would train bottom-up attention, in fact the benefits seem to be mainly improvements in the effectiveness of the top-down attention system. Unfortunately, only shoot-’emup rapid action games, of the type that parents hate, seem to have these effects.

The changes appear to be a direct effect of video game playing. Alternately, you might imagine that people with better visual attention would find video games more rewarding and so be more likely to play them, which would be an example of reverse causation. But researchers ruled out that interpretation because, in some studies, college students who did not play regularly were randomly assigned to practice action video games (for example,

Grand Theft Auto

or

Call of Duty

). The control group spent an equal amount of time practicing nonaction video games (

Tetris

,

The Sims

). The training improved several aspects of visual attention, but only in the action video group. This group also improved in contrast sensitivity (the ability to see faint outlines, like cars in fog), an effect that lasts for years after training. Players react more quickly than nonplayers, with no difference in the number of errors they make in their reactions.

SPECULATION: DOES INTERNET USE REDUCE EMPATHY?

Who isn’t annoyed by the oblivious person in line who won’t get off his phone to talk to the cashier? Since 2000, there has been a sharp drop in empathy in the U.S., leading to experiences like the poor clerk’s. A meta-analysis found that today’s college students are 40 percent less likely than their counterparts two or three decades ago to agree with statements like “Before criticizing somebody, I try to imagine how I would feel if I were in their place.” In other surveys, many U.S. citizens report feeling that people have become less kind and considerate over the past decade.

This decline has only been identified recently, so its causes are not known for certain, but the rise of electronic media is a prime suspect. The most striking environmental change over this time period is that modern college students have grown up with electronic communications and video games as a constant presence in their lives. Texting has taken over from phone conversations, and many teens text even in situations where they could turn and speak to each other in person.

These changes could interfere with the development of empathy in a variety of ways. The culture of online interaction in communities like Facebook encourages people to ignore others who are perceived as overly demanding, which might reduce tolerance for people with problems in face-to-face interactions. Exposure to video game violence might desensitize children to the pain of others. Perhaps most important, children who learn about social interactions online are deprived of a variety of emotional cues, such as facial expressions, that could help them to appreciate the feelings of other people. Without such real-world experience, empathy may not develop correctly—and that could be very costly for all of us.

Similar randomized experiments cannot be done in children because it would be unethical to expose them to the violence in action games. We would guess

that if there is a difference between children and college students, it is likely to be that young brains are more plastic than adult brains. Researchers are looking for nonviolent games with similar beneficial effects, but they have not yet managed to find any.

Before age two, electronic entertainment has no benefit and clear costs.

Children who are already action video game players at home show most of the same advantages over nonplayers (or players of nonaction games) that are found in college students. Across all ages from seven to twenty-two years, players are better able to orient their attention to a cued location, compared to nonplayers of the same age (in the conflict cue task, see

p. 116

). Distractor arrows (in the incongruent condition) slow the responses of players proportionately more than those of nonplayers, suggesting that video game players pay attention to a broader field of view. Players are also better than nonplayers at detecting a target against a background of distractors, at rapidly processing a stream of visual inputs, and at tracking multiple targets simultaneously. Because video game players are mostly boys, these effects of practice may lead to gender differences in attentional processing, which have not existed in previous generations.

Another recent change in children’s sensory experiences is the rise of multitasking. In the U.S., children now fit 8.5 hours of media use into 6.5 hours per day, on average, by doing multiple things at once (text messaging while watching TV or listening to music while playing video games). Almost all of us believe that we can multitask. However, the brain cannot concentrate well on more than one thing at a time. A major source of interference between tasks seems to be the limited capacity of the prefrontal cortex, a key aspect of the brain’s executive control system.

Many aspects of brain function, such as walking or driving a familiar route, do not require direct conscious control. Planning your actions, though, does require attention, as you’ll notice the next time you get distracted and end up at a familiar destination when you meant to go somewhere else. People who claim to do multiple attention-demanding tasks at once are actually switching between the tasks repeatedly. Every transfer of attention from one task to another requires resources, as your brain must remember or reconstruct where you were on the abandoned task when you come back to it. The first task can also interfere with the representation of the second task in your memory. For these reasons, switching back and forth between tasks takes more time than completing the same tasks one by one in sequence. What cognitive psychologists call

costs of switching

reduce performance on individual tasks. If both tasks are highly practiced, this switching cost can be reduced or perhaps in rare cases eliminated. Under no circumstances, though, is it more efficient to do multiple attention-demanding tasks at once than to do them separately. In short, multitasking is a myth.

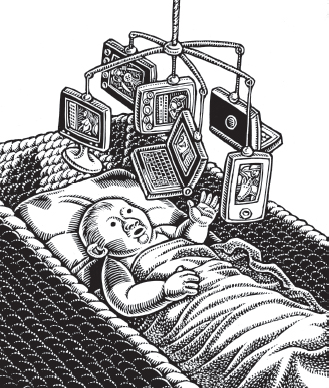

PRACTICAL TIP: BABY VIDEOS DO MORE HARM THAN GOOD

Almost all children today start watching TV before they are two years old. This is not good news for their future. Marketers claim that baby videos, such as those available from Baby Einstein and Brainy Baby, can give your child’s brain a head start, but research shows that the opposite is true.

As we have discussed, sensory experience is important for brain development, particularly the growth and retraction of synaptic connections, which is vigorous during the first three years of life. We would expect that children’s brains should be affected by watching TV for as much as a third of their waking hours during this developmental window. The key question is

how

are they affected?

Babies’ brains are optimized to learn from social interaction. For example, babies learn poorly from exposure to a second language on video (see

chapter 6

). The electronic babysitter reduces the time that infants spend interacting with other people, which can impair many aspects of their development. Even if you watch TV with your baby in the room, without intending for her to watch it, its presence interferes with her play and reduces the amount of social interaction between you.

Multiple studies have shown that infant TV watching is correlated with poor language development. U.S. babies of seven to sixteen months who spend more time in front of the screen know fewer words. Two or more hours per day of screen time before the first birthday is associated with a sixfold increase in the risk of language delay in Thai children. Even

Sesame Street

viewing by babies correlates with language delay, though this program has lasting beneficial effects on three- to five-year-olds. Exposure to baby videos is also associated with reduced cognitive ability at age three.

The quick cuts and bright colors that are typical of baby videos may also interfere with the normal development of attention. Before ten months of age, your infant cannot direct his attention voluntarily (see

chapter 13

). Exposure to attention-grabbing stimuli like fast-paced entertainment programs may make the transition to voluntary attention more difficult. In a longitudinal study, children who watched violent shows before age three were more than twice as likely to have ADHD at ages five to eight. It is easy to imagine that parents of ADHD children might be tempted to use TV to occupy their child, creating a vicious cycle (see

chapter 28

).

No reliable research shows that TV watching has any benefit for babies. France recently banned programming directed at infants, but it is unlikely that the U.S. will follow suit. Instead, parents need to protect their babies by keeping them away from the TV until they are at least two years old.

The cost of chronic multitasking may include diminished performance when single-tasking. One study found that college students who multitask more often performed worse than those who multitask less often at tests of distractibility and task-switching ability. Students who spent more hours using the Internet also tended to spend more time using multiple types of media simultaneously. The performance of high multitaskers was more severely impaired by distractors, compared to low multitaskers, though the two groups performed equally well when no distractors were present. In other tasks, high multitaskers also had more trouble ignoring irrelevant items in their memory and switching back and forth between two sets of rules. One thing we don’t know is whether naturally distractible people are more likely to multitask or whether multitasking actually increases distractibility. Either way, though, if your children spend a lot of time multitasking, it’s not likely to be good news for their ability to concentrate.

As we’ve discussed throughout this book, your children’s life experiences influence their brains in a variety of ways. Because the rise of electronic media is both so recent and so significant, scientists are working hard to determine its effects on child development. We do know that young children’s brains are strongly influenced by one-on-one interactions with caring adults, which cannot

be replaced by anything that appears on a video screen. Before age two, electronic entertainment has no benefit and clear costs (see

Practical tip: Baby videos do more harm than good

). For older preschoolers, educational TV can be beneficial, while certain programs are more likely to do harm. For example, children who watched

Dora the Explorer

or

Blue’s Clues

at age two and a half had better language skills, while those who watched

Teletubbies

had worse language skills than average. In school-age children, electronic media are a mixed blessing, improving some cognitive capacities, while perhaps impairing others.