Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College (29 page)

Read Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College Online

Authors: Sandra Aamodt,Sam Wang

Tags: #Pediatrics, #Science, #Medical, #General, #Child Development, #Family & Relationships

MYTH: THE RIGHT HEMISPHERE IS THE EMOTIONAL SIDE

You’ve probably heard people talk about being

left brained

when they mean logical and

right brained

when they mean emotional. This hypothesis was formulated several decades ago, before the invention of functional brain imaging. It is true that the emotional content of speech (its tone or prosody) is processed by language areas on the right side of the brain, but in general emotions are equally effective in activating regions on both sides of the brain. And the two halves of the brain are so heavily interconnected that it makes no sense to claim that an entire half is somehow left out of the mix.

The basic principle is not that the left/right brain is rational/emotional, but that specific functions are localized. Evolution has selected for brains that use the least axonal “wiring,” so related functions often sit near one another in the brain. In many cases, different aspects of a function get collected in one particular brain area, which can be on the left or on the right. This pattern is especially noticeable in big-brained apes like us.

For emotions, there may be an interesting division of function between the right and left lateral prefrontal cortex. Many patients who have damage to this region on the left side of the brain become depressed, while patients whose damage is on the right side may become inappropriately cheerful or manic (though this finding is not completely consistent across studies). These outcomes suggest that the left lateral prefrontal cortex may be specialized for positive emotions and the right for negative emotions. A related version of this idea holds that the left side carries signals for approach (getting closer to the situation), and the right side for avoidance (staying away from the situation). The only practical difference between the two ideas is the characterization of anger, a negative emotion that makes you want to approach the person causing it (in order to punch his lights out).

Brain activity recorded via electrical signals from the scalp supports this hypothesis. The difference between hemispheres shows up very early in development. Some researchers have suggested that the balance between the right and left prefrontal cortex may be the source of temperamental differences in emotionality, determining whether a particular child has a stronger tendency to respond to the world by approaching or withdrawing.

As the cortex develops, around the middle of the second year of life, children begin to display the secondary emotions: pride, shame, guilt, jealousy, and embarrassment. These social emotions become more situation-specific as children come to appreciate the importance of their own behavior in causing particular outcomes. For example, at six, children feel guilty whenever something goes wrong, but by nine, they understand that guilt is only appropriate when their actions were responsible for what happened.

DID YOU KNOW? SELF-CONTROL PROMOTES EMPATHY

Babies often cry when they hear another baby crying, in the contagious form of empathy (see

chapter 19

). True empathy, the ability to appreciate other people’s feelings, develops by age five. Children show great gains in self-control during that same period, and individual children who have better self-control also show more empathy and a more developed conscience. Similarly, children who are better at inhibiting an automatic behavioral response (for example, by saying “day” when shown a picture of the moon, instead of “night”) tend to have a more sophisticated ability to imagine what other people are thinking and feeling, even when age, intelligence, and working memory are taken into account.

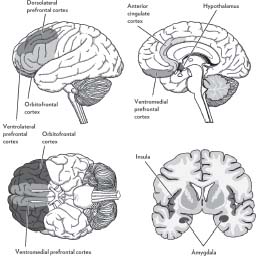

What’s the connection? To develop empathy, children need to have a certain ability to entertain alternatives and hypothetical possibilities, which is part of self-control. The prefrontal and anterior cingulate regions of the cortex are involved in both self-control and empathy, so cortical development may limit children’s ability to understand other people’s feelings and their ability to control themselves. As part of the brain’s attention-regulation system, the anterior cingulate is active when children concentrate on their own behavior or on other people’s feelings. Such concentration may be a necessary first step in the development of both these important functions. The prefrontal cortex is important for behavioral inhibition, and it is active during theory-of-mind tasks, which require people to concentrate on what someone else could know.

As we pointed out in

chapter 10

, the neocortex actively interprets external experiences, for instance, turning raw sensory information into a coherent sense of vision. As emotion-related cortical areas mature, they also gain the ability to shape how emotions are experienced. The anterior cingulate, insular, and orbitofrontal regions of the cortex combine numerous brain signals to construct the conscious experience of emotion. The anterior cingulate may be involved in

seeking understanding or control over emotions. The orbitofrontal cortex is important for evaluating the social context of your choices, while the anterior insula represents your internal state, receiving signals from a wide range of brain areas about everything from thirst to cigarette craving to love.

The conscious perception of an emotional state is influenced by memories, by inferences about causality, by ideas about how to respond to the situation, and by the social context. For this reason, in addition to lacking control over their emotions, young children probably do not experience emotional states as richly as adults do until the cortex matures.

Parents who are more sensitive to their infant’s needs and respond quickly to emotional cues tend to raise children who are better at regulating their own emotions.

When babies first start to direct their own attention, by eight to ten months of age, they start to use distraction to manage their emotions, for instance, by turning to a new activity when a toy is taken away. Indeed, infants who can direct their attention to one particular thing for long durations express more positive emotions as babies and show better self-control later in life. As children’s brains develop more self-control in general, their ability to regulate their emotions grows as well, as the same brain circuits are involved in all forms of self-control (see

chapter 13

). Children’s brains apparently have to work harder than adults’ when trying to inhibit an ongoing behavior. Older children gradually learn to use more sophisticated strategies, such as reinterpreting the meaning of an event to manage their emotional reactions (“That teacher doesn’t hate me; she’s just in a bad mood because Justin’s been talking back to her all day”). As they get better at managing their emotions, children also improve their ability to hide emotions, allowing them to smile at Grandma for giving them a sweater—no matter what it looks like.

Until their own regulatory capacity is fully developed, your children rely on you to moderate their emotions, by soothing or distracting them, and to help them learn how it’s done. Parents who are more sensitive to their infant’s needs

and respond quickly to emotional cues tend to raise children who are better at regulating their own emotions. Maternal warmth and the strength of the bond between mother and child (see

chapter 20

) are also correlated with children’s self-control ability. In other words, a good relationship with Mom may be a long-term source of willpower. Finally, parents who explicitly coach their children on the experience of emotions, by labeling and validating feelings and suggesting constructive ways to deal with them, tend to have children who are better at regulating their emotions later in life. Since children with poor self-control ability are prone to aggression and are at risk of developing conduct disorders and ADHD (see

chapter 28

), helping them self-regulate can do them a great service.

The prefrontal cortex, the newest part of our brains in evolutionary terms, is very slow to mature, developing last in the back-to-front progression of the neo-cortex (see

chapter 9

), but its capacities are worth waiting for. During the first two years, its neurons increase their complexity and add many synapses. After that, this part of the cortex enters the stage of experience-dependent synapse elimination (see

chapter 5

). Its connections do not become completely adultlike until late adolescence, and long-distance connections through white matter develop even more slowly. So your child’s ability to regulate his emotions and to recognize and respond appropriately to the emotions of others continues to improve throughout childhood. That promise should give parents something to look forward to on those days when life with a toddler is just plain exhausting.

Chapter 19

EMPATHY AND THEORY OF MIND

AGES: ONE YEAR TO FIVE YEARS

The first time your child tries to pull the wool over your eyes, take a minute to appreciate the achievement. Although we want children to tell the truth, gaining the ability to lie convincingly is a notable step in mental development. Even to attempt it means the child thinks she can manipulate an adult’s knowledge. It also means that she knows that others have thoughts, some of which contradict reality. Understanding that others can have false beliefs is part of normal development—and appears to be unique to people.

People are intensely social animals. We form alliances, jockey for position, comfort one another, and play games. When we’re not doing that, we talk about each other, speculating on one another’s motives. All these activities require a capacity to think about other people’s state of mind. Here we will describe how these brain systems come online—as well as give you some tips on watching these qualities grow in your son or daughter.