Vaccinated (23 page)

Authors: Paul A. Offit

Hilleman's lack of recognition didn't end with the mumps vaccine. After Wolf Szmuness completed the trial of Hilleman's blood-derived hepatitis B vaccine, he published his findings in one of medicine's most prestigious journals, the

New England Journal of Medicine

. Newspapers and magazines declared the importance of Szmuness's work. Radio stations interviewed him about his findings. Television stations showed video clips of Szmuness inoculating men who had volunteered for the trialâfootage provided by Merck. When professional societies held meetings to discuss the hepatitis B vaccine, they called Wolf Szmuness. When advisory bodies wanted to determine exactly how the hepatitis B vaccine should be used in the United States, they called on Szmuness for answers. As far as the press, the public, and public health agencies were concerned, Wolf Szmuness had developed the hepatitis B vaccine.

But Szmuness hadn't developed the hepatitis B vaccine. Maurice Hilleman had. Szmuness's seminal publication in the

New England Journal of Medicine

contained the names of nine authors; Hilleman's wasn't among them. As a consequence, the press didn't seek Hilleman out, and doctors, nurses, and public health officials had no idea that he was the inventor. “I wanted to stand back and let Wolf determine whether the vaccine worked or not,” recalled Hilleman. “I thought that if my name appeared on the paper, or if I was the one put in front of the television cameras or radio microphones, people would think that I was selling something. Because I was in industry and it was an evaluation of my work, ethically I felt that I had to stand back.” Because of his own reticence and his company's discomfort about promoting him, few people recognized Maurice Hilleman for what he considered to be his greatest accomplishment.

Hilleman's work on the measles vaccine has also been largely ignored. Between 1989 and 1991 measles virus reemerged in the United States; about ten thousand people were hospitalized, and more than one hundred were killed by the virus. In response to the epidemic, the CDC recommended that all children receive a second dose of measles vaccine during childhood. The recommendation worked. In 2005, federal advisors, vaccine makers, the media, and the public gathered in Atlanta to hear the results of the new recommendation. The CDC reported that during the previous year only thirty-seven new cases of measles had occurred; no one had been hospitalized, and no one had been killed by the virus. Public health officials were excited about the possibility of finally eliminating measles from the United States. During the meeting, the chairman of the federal advisory committee recognized Sam Katz as the developer of the measles vaccine. Katz was a liaison member of the committee. “I'd just like to take a moment to recognize the contributions of Sam Katz,” said the chairman. “He is the man who gave us the measles vaccine.” Katz received an ovation. A humble, honest man, Katz held his hands up and tried to quiet the audience. “That's enough,” he said.

Sam Katz and the Boston team made an important contribution by isolating measles virus and weakening it in their laboratory. They deserved an ovation. But their vaccine wasn't weak enough; it caused high fever and rash in as many as four of every ten children who received it. A better vaccine was made by Maurice Hilleman, who, unfortunately, never received a standing ovation for his achievement.

Â

F

OR ALL OF HIS ACCOMPLISHMENTS,

M

AURICE

H

ILLEMAN NEVER WON

the Nobel Prize. Because the prize cannot be awarded posthumously, he never will win it.

Alfred Nobel decided to create his prize after reading his own obituary. Born on October 21, 1833, in Stockholm, Sweden, Nobel was interested in explosivesâspecifically those that could be used in coal mines. At the time, miners used black powder, a form of gunpowder. But Nobel was interested in a much more powerful, volatile explosive: nitroglycerin. In 1862 he built a small factory to make it. One year later, Nobel invented a practical detonator that consisted of a wooden plug inserted into a metal tube; the plug contained black powder, and the tube contained nitroglycerin. Two years later Nobel improved his detonator by replacing the wooden plug with a small metal cap and replacing the black powder with mercury fulminate. This second invention, called a blasting cap, ushered in the modern age of explosives.

Nitroglycerin, however, remained difficult to handle. In 1864 Nobel's nitroglycerin factory blew up, killing Nobel's younger brother Emil as well as several others. Undaunted, Nobel continued to work with the volatile chemical. By 1867 he had found that he was able to stabilize nitroglycerin by adding dirt containing large quantities of silica. He called his third invention dynamite, from the Greek

dynamis

, meaning “power.” Dynamite provided armies with a new deadly weapon and made Alfred Nobel a very rich man.

In 1888 Alfred's brother Ludvig died in Cannes. French newspapersâconfusing Ludvig with Alfredâprinted Alfred's obituary under the headline “Le marchand de la mort est mort” (The merchant of death is dead). Nobel had always believed that his explosives, apart from their practical value, would be used as weapons of peace, not war. “My dynamite will sooner lead to peace,” he said “than a thousand world conventions. As soon as men find that in one instant whole armies can be utterly destroyed, they surely will abide by golden peace.” (Where have we heard this before?) After reading “his” obituary, Nobel realized that he was wrong; he would be remembered as a war maker, not a peacemaker. So on November 27, 1895, Nobel revised his will. “The whole of my remaining real estate shall be dealt with in the following way: the capital shall be annually distributed in the form of prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to mankind [and it will be] divided into five equal parts: physics, chemical discovery or improvement, physiology or medicine; the field of literature; and the best work for fraternity between nations and promotion of peace.” One year after revising his will, on December 10, 1896, Alfred Nobel died of a stroke in San Remo, Italy. Five years later, the king of Sweden awarded the first Nobel Prize. Today, no award is more coveted.

In accordance with Nobel's will, scientists working at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm determine the winner of the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. But scientists are often more enamored with technological innovations than with public health achievements. As a consequence, the most important discoveries in the field of medicine have not been given to those who have saved the most lives.

Hilleman's accomplishments in the field of vaccines weren't the only ones snubbed by the Nobel Prize committee. Jonas Salk's polio vaccine caused a dramatic decrease in the incidence of polio in the United States and eliminated polio from several other countries. Within days of the announcement that his vaccine worked, Salk was honored at the White House. During a ceremony in the Rose Garden, in a voice trembling with emotion, President Dwight Eisenhower said, “I have no words to thank you. I am very, very happy.” But Jonas Salk never won the Nobel Prize. Months after Salk's death, Renato Dulbecco, winner of the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1975 for his work on viruses that cause cancer, wrote Salk's obituary for the scientific journal

Nature

. “For his work on polio vaccine, Salk received every major recognition available in the world from the public and governments. But he received no recognition from the scientific worldâhe was not awarded the Nobel Prize, nor did he become a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. The reason is that he did not make any innovative scientific discovery.” Although Salk's vaccine was one of the greatest and most anticipated public health achievements of the twentieth century, the Nobel Prize would never be his.

A few years later, Albert Sabin developed his polio vaccine. By 1991 Sabin's polio vaccine had eliminated polio from the Western Hemisphere and much of the world. By 2015, if Sabin's vaccine continues to be given in India, Africa, Indonesia, and Asia, it will likely eliminate polio from the face of the earth. Sabin was a genius. Recognized by his colleagues, he won many awards and honors, including induction into the National Academy of Sciences. The Sabin Vaccine Institute in Washington, D.C., stands as a permanent shrine to honor the man. But Albert Sabin, like Jonas Salk, never won the Nobel Prize. The only Nobel Prize for the development of a polio vaccine was given to the Boston research team of John Enders, Fred Robbins, and Tom Weller. And that's because it was the Enders team that figured out how to grow polio virus in cell culture, allowing both Salk and Sabin to make their vaccines.

Maurice Hilleman made his measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines by weakening viruses in laboratory cells. His efforts led to the virtual elimination of those diseases in the United States. But Hilleman wasn't the first person to figure out how to grow viruses in cell culture, and he wasn't the first person to find that human viruses could be weakened in animal cells. That person was Max Theiler. So it was Theiler, in 1951, who won the Nobel Prize.

Hilleman considered his hepatitis B vaccine to be his greatest single achievement. His blood-derived vaccine, made by purifying Australia antigen from the blood of homosexual men in the late 1970s, was a technological tour de force. But Hilleman didn't discover Australia antigen; Baruch Blumberg did. And it was Blumberg who won the Nobel Prize for his finding. (Many scientists believe that the prize should have been awarded to Alfred Prince, the first to realize that Australia antigen was part of hepatitis B virus.)

Hilleman did, however, perform one series of studies worthy of the prize: his interferon research. Hilleman had been the first to purify interferon, determine its biological properties, and propose a mechanism for its action. Months before his death, knowing that this was Hilleman's last chance, several scientists lobbied members of the Nobel Prize committee, holding up Hilleman's interferon work as worthy of the prize. But one key member of the committee pointed out that the Nobel Prize in medicine would not be given to anyone who worked for a company.

Adding to the frustration of failed attempts to gain for Hilleman the recognition he deserved, the Nobel Prize committee has occasionally honored research that was far from deserving. For example, in 1926 the committee awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine to Johannes Fibiger for his discovery of a worm that caused stomach cancer in rats, figuring that this was an important breakthrough in what causes human cancer. But worms don't cause cancer in people. Julius Wagner-Jauregg won the prize in 1927 for discovering that malaria parasites could be used to treat syphilis; apart from being useless, the therapy was dangerous. Finally, in 1949 the committee awarded the prize to Egas Moniz of Portugal for discovering the value of lobotomyâthe removal of a lobe of the brainâin treating certain psychoses. In the middle of the twentieth century, lobotomies were popular. Doctors performed a lobotomy on John F. Kennedy's sister Rosemary; Ken Kesey had one performed on the fictional Randle P. McMurphy in his book

One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest

(Jack Nicholson played McMurphy in the 1975 movie); and the

New England Journal of Medicine

hailed this therapy as the birth of “a new psychiatry.” But the procedure proved worthless and cruel.

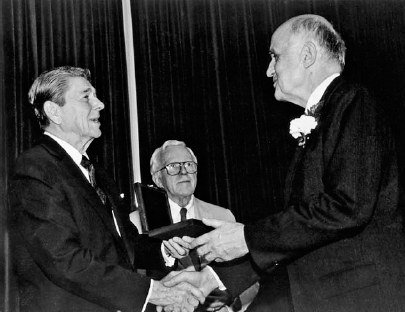

Maurice Hilleman receives the National Medal of Science from President Ronald Reagan, 1988.

Â

A

LTHOUGH NOT RECOGNIZED BY THE PUBLIC, THE PRESS, OR THE

Nobel Prize committee, Hilleman was honored by his colleagues. In 1983 he received the Albert Lasker Medical Research Award; in 1985 he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences; in 1988 he received the National Medal of Science from President Ronald Reagan; in 1989 he received the Robert Koch Gold Medal; in 1996 he received a Special Lifetime Achievement Award by the WHO; and in 1997 he received the Albert B. Sabin Lifetime Achievement Award. “Every once in a while you come across a scientist whose list of accomplishments shine so brightly that you're almost blinded by them,” recalled the NIH's Tony Fauci. “Most scientists would have been thrilled to have achieved just one of the scores and scores of Maurice's accomplishments.”

Although he never received the Nobel Prize, because of Maurice Hilleman, hundreds of millions of children get to live their lives free from infections that at one time might have permanently harmed or killed them. In the final accounting, no prize is greater than that.

We remember the tale of the wonderful one-hoss shay

That was built in such a marvelous way

It lasted for a hundred years to the day

Then collapsed, all at once, in total decay

OLIVER

W

ENDELL

H

OLMES

(M

AURICE

H

ILLEMAN INCLUDED THIS POEM AT THE BEGINNING OF AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY THAT WAS FORTY PAGES LONG AT THE TIME OF HIS DEATH)

I

n 1984, when Maurice Hilleman was sixty-five years old, Merck, in accordance with company policy, asked him to retire. He refused. After months of negotiation, Merck, for the first time in its history, relented, allowing Hilleman to direct the newly created Merck Institute for Vaccinology. For the next twenty years Hilleman came to work every day, often staying late. There, he pored through recent scientific publications and wrote seminal review articles and opinion pieces about bioterrorism, the history of biowarfare, pandemic influenza, the vaccine enterprise, the history of vaccines, and the constant war waged between human beings and microbes. Not many scientists publish into their mid-eighties, but Hilleman's publications after his retirement continued to shape the way that scientists thought about vaccines and the diseases they prevented. During his last twenty years, Maurice welcomed scientists from his company and the world, all seeking the wisdom of his experience.

Â

O

N JANUARY

26, 2005,

THREE MONTHS BEFORE HIS DEATH, MEMBERS

of the scientific and medical community came to Philadelphia to honor Maurice Hilleman and to celebrate his life and work. They gathered at the American Philosophical Society.

Founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1743 and housed behind the white marble façade of the old Farmers and Mechanics Bank, the American Philosophical Society is the oldest surviving scholarly society in the United States. (In the eighteenth century “natural philosophy” meant the study of nature. If founded today, it would have been called the American Scientific Society.) Members of the society included founding fathers such as George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Benjamin Rush, James Madison, and John Marshall as well as scientists such as John Audubon, Robert Fulton, Thomas Edison, Louis Pasteur, Albert Einstein, Linus Pauling, Margaret Mead, Marie Curie, and Charles Darwin; the society's library houses a first edition of Hilleman's beloved

The Origin of Species

.

Maurice Hilleman with daughters Kirsten (far left) and Jeryl and wife Lorraine, Vail, Colorado, December 1982. Maurice is the only one not wearing skis.

Some of the best scientists of the twentieth century came to honor Hilleman that day. Robert Gallo (co-discoverer of HIV), Anthony Fauci (director of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases), Erling Norrby (a member of the Nobel Prize Committee), Hilary Koprowski (the co-developer of the modern rabies vaccine), Thomas Starzl (pioneer of liver transplantation), Roy Vagelos (developer of cholesterol-lowering agents), and Margaret Liu (an early pioneer of DNA vaccines) all stood up to talk about how Hilleman's accomplishments had instructed or dwarfed their own. At the end of the evening Hilleman thanked those in attendance. In a quiet, tired voice, he spoke of his friends, his family, and his good fortune. But Hilleman never forgot where he came from, recalling at the end of the symposium that although it was a wintry night on the streets of Philadelphia, “it was forty below in Montana.”

Some in the audience cried, lamenting the end of a phenomenon.

Â

D

URING THE SYMPOSIUM,

H

ILLEMAN, WHO LIKED TO THINK OF HIMSELF

as tough and unmovable, said, “The most apt description of me was by Roy Vagelos, who said that on the outside I appeared to be a bastard but that if you looked deeper, inside, you still saw a bastard.” But Hilleman's rough exterior hid a generous, softer side; he chose a career that benefited people because he loved people. When a friend at the CDC Foundation was diagnosed with breast cancer, he devoted himself to making sure that she got the care she needed. When neighborhood children asked to interview him for their science projects, he always complied; often spending hours carefully explaining his work. He was “the warmest family-oriented person that I've ever met,” said Vagelos. “As tough as he was on people,” recalled Fauci, “he did it in a way that was clear that he was trying to get a message to people and not to put anybody down. He just wanted straight talking. And when people veered from straight talking, he did not hesitate to get up and say, âYou're full of crap.' He was an adorable grump.” His daughter Kirsten agreed. “People asked me what it was like to have Maurice as a father,” she said. “It was wonderful. When we were little, our father traveled for weeks at a time and was a workaholic, but, strangely, I have almost no recollection of those long absences. What I remember best are those great stories he told about growing up in Montana; him singing me to sleep every night [with

The Sound of Music

song] âEdelweiss.' And the many long hours we spent together in the basement conducting scientific experiments and building models. We built hearts, feet, hands, eyeballs, skeletons, transistor radios, and even a Model T Ford. My dad prided himself most on being a cynic, and yet he has accomplished so much in his life. His vaccines have saved so many lives that I believe that deep down under all of that crusty humor, he is an eternal optimist.” “[He] taught me virtually everything that I knew,” said Jeryl. “I learned to trust in logic and science while still leaving room for the mystical. My father gave me the greatest gift anyone can give another person. He believed in me.”

Maurice Hilleman shows grandson Dashiell a laboratory plate containing bacteria grown from Dashiell's diaper, 2004.

At the symposium to honor her husband, Lorraine recalled their forty-two-year marriage. “Many of you know how we met,” she said. “He was interviewing me [to coordinate] studies being done at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia for clinical trials of the measles and mumps vaccines. The interview was going very well, and he was pleasant enough. And suddenly he said, âHow old are you?' I told him I was twenty-nine. And he said, âOh, I thought you were thirty-five.' In spite of that we were married a short time later. And now for almost forty-two years he truly is a marvel of a man. And I am his lady.”

Â

D

URING THE FEW MONTHS BEFORE HIS DEATH,

H

ILLEMAN TALKED A

great deal about the two men who had influenced his choices: his father, Gustave, and the man who raised him: his father's brother, Robert. “Gustave was not a bad man,” recalled Hilleman. “But he was changed at the time of [my mother's] death and the shock it brought and the new responsibilities it entailed. He became newly charged with religious zeal and his need to get his family to heaven, best accomplished by having all his boys become ministers and his daughter marrying one. He sang loudly and prayed from his pew in the eighth row and continuously proclaimed that âthe Lord would provide,' no matter what adversity would befall him. To provide medical care for his family, he decided that he should enroll in a correspondence school to become a chiropractor. In chiropractic belief at that time it was claimed that all disease is caused by an impingement on the spine. Automatically, this threw out the infectious germ theory for disease and, above all, prohibited prevention by vaccination. I was [not allowed] to have any vaccines.” (Perhaps this is one of medicine's greatest ironies.)

Hilleman's adoptive father, Robert, was different. “Bob was the antipathy and opposite of Gustave: freethinking, liberal, considerate, and, above all, highly intelligent. Bob's religion was practiced in good deeds. He would order up and deliver goods from out of stateâmargarine and other products not allowed by the dairy lobby. Everything was at cost, no profit. He sold affordable Lutheran life insurance to cover minimal family needs. And he provided informed legal assistance and wrote wills for those who couldn't pay for lawyers.”

Faced with his imminent death, Hilleman thought a lot about these two men. At the end, he didn't turn to the religion of his father. Rather, as he had throughout his life, he sought solace in the reason and freethinking of his uncle. The ultimate experimentalist, Hilleman wanted to see whether one particular theory about cancer vaccines worked. So he tried it on himself.

In the 1940s researchers showed that if malignant tumor cells were taken from one mouse and injected into another, they caused cancer in the second mouse. But if the malignant tumor cells were weakened and injected into mice and then the same mice were injected with virulent cancer cells, they wouldn't get cancer. Mice could be vaccinated against cancer. For a long time it wasn't clear why this happened. Then a graduate student named Pramod Srivastava, now a professor of immunology at the University of Connecticut, figured it out. He took tumor cells, broke them open, separated different parts of the cells, and found that one particular group of proteins, called heat-shock proteins, protected mice against cancer. Heat-shock proteins are usually found in cells under stress caused by heat, cold, lack of oxygen, or cancer. Srivastava found that heat-shock proteinsâwith small fragments of cancer proteins in towâwere trying to warn the immune system that a cancer was growing. Srivastava reasoned that if he could take the cancer, purify the heat-shock proteins containing cancer proteins, and inject large quantities of this combination back into mice, then he could eliminate the cancer. Researchers working with many different cancers found that this worked in mice and rats. But they didn't know if it worked in people. When Hilleman wanted to see if heat-shock proteins could eliminate his own cancer, studies in people were under way, but none had been completed.

Hilleman sent his cancer cells, taken from the space between his lungs and his chest wall, to a company that specialized in purifying heat-shock proteins. He was hoping that he would live long enough to inject himself with 25 micrograms of these proteins once a week for four weeks. But Hilleman's cancer overwhelmed him before he could complete his final experiment.

Â

O

N

A

PRIL

14, 2005, M

AURICE

H

ILLEMAN WAS FINALLY LAID TO REST

near his home in Chestnut Hill, Pennsylvania. “In Montana, when there was something to celebrate,” recalled Hilleman, “everybody would get together, sit on a log, get a fresh bucket of water, and pass around a cup.” Hilleman had watched this scene many times. But Maurice Hilleman never rested, never celebrated, never stood back to enjoy what he had done. He was always driven to make the next discovery. “We got another license [for a vaccine],” he recalled. “So what. We're not going to sit around and celebrate. We've got new vaccines to make. You've got a bunch of mountains. When you climb one, then you've got another one to climb and another one. When you get to the top of one mountain, interest declines. There's more work to be done.”

One hundred years from now we'll open the National Millennium Time Capsule commissioned by Bill and Hillary Clinton. We'll find the clear plastic block containing Maurice Hilleman's vaccines. We'll also find an artifact from Peggy Prenshaw, winner of the National Humanities Medal. Prenshaw submitted the words of author William Faulkner when he accepted the Nobel Prize for literature in 1950: “I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.” Maurice Hilleman represented that spirit: a man whose work was unprecedented and whose gifts will remain forever, unmatched.