Vaccinated (2 page)

Authors: Paul A. Offit

Maurice Hilleman, 1925.

When he was eight years old, Hilleman almost died of suffocation caused by diphtheria: “I was proclaimed near dead so many times as a kid. They always said I wouldn't last till morning.”

Although legally adopted and raised by his aunt and uncle, Hilleman lived within a hundred yards of his natural father, a strict Lutheran. He railed against his father's conservative fundamentalism: “People in Montana were good people. It gets below zero. They helped each other out. They were a community. The church maintained law and order and provided a social structure and adhesiveness that was very important on the western front. It was a decent, ordered society. But I just couldn't buy all of the mythology. And I didn't want to be strapped down by the church's dogma.” As a boy, Hilleman found solace in the pages of Charles Darwin's

The Origin of Species

, which he read and reread. “I was enthralled by Darwin because the church was so opposed to him,” he recalled. “I figured that anybody who could be so universally hated had to have something good about him.” Hilleman read everything he could find about science and the great men of science. His heroâand the hero of many Montana schoolchildrenâwas Howard Taylor Ricketts.

In the early 1900s, a mysterious disease attacked residents of the Bitterroot Valley in western Montana, causing high fever, intense headaches, muscle pain, low blood pressure, shock, and death. Montana's governor, Joseph Toole, called on Howard Ricketts to find the cause. A Midwesterner and a graduate of Northwestern University, Ricketts immediately recruited students from Montana State University in nearby Bozeman to help. Many of them later died of the disease. Much to his surprise, Ricketts found that the deadly infection was caused by a bacterium found in ticks. “He was a god out there,” recalled Hilleman. Today the bacterium is called

Rickettsia rickettsii

, and the disease is called Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Custer County High School, 1937

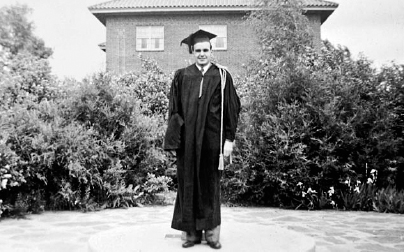

Maurice Hilleman, graduation day, Montana State University, 1941.

As a teenager attending Custer County High School in Miles City, Hilleman landed a job as assistant manager at the J. C. Penney store, helping “cowpokes pick out chenille bathrobes for their girlfriends.” In Depression-era Montana, this was a highly sought after position, and it ensured Hilleman's future. But one of Hilleman's brothers suggested that Maurice forget about J. C. Penney and go to college. “If you lived in Miles City and you were smart, you went to Concordia College and then to the seminary to be ordained as a Lutheran preacher. But I wasn't going to do that.” So Hilleman applied for and won a full scholarship from Montana State University. In 1941 he graduated first in his class, having majored in chemistry and microbiology.

After graduation, Hilleman wanted to go to medical school but again couldn't afford it. “I couldn't see any possibility of doing that,” he said. “You had to put yourself through residency. Where was I going to get the money?” So Hilleman applied to ten graduate schools, hoping to eventually get a doctorate in microbiology. “I came from Montana State University, this small agricultural school. These people would see a letter from some cowboy in Montana, [and] I assumed that it would be in the wastebasket pretty quick.” On the top of Hilleman's list was the University of Chicago. “To a westerner the United States ended in Chicago,” recalled Hilleman. “Chicago was the mecca. The great university there was the intellectual center at the time.” Hilleman was accepted by all ten schools, each offering a full scholarship: “I got into Chicago. I got into them all. Do you believe that? I was on top of the mountain.”

Life in Chicago wasn't much easier than life on the farm. “He weighed 138 pounds,” recalled Hilleman's wife, Lorraine. “He ate one meal a day; that was all he could afford. And I know that he slept with bedbugs, too. He would put bars of soap around to catch [them].” Chicago's academic style was also challenging. Hilleman recalled, “The Chicago system, as far as the professor was concerned, was âDon't bother me and let me know when you discover something.'” Hilleman struggled to find a research project, eventually settling on chlamydia, a sexually transmitted pathogen that scientists thought was a virus. (Chlamydia infects about three million people in the United States every year, and, because it scars the fallopian tubes, causes infertility in tens of thousands of women.) Within a year, Hilleman found that chlamydia wasn't a virus at all; it was a small, unusual bacterium that, unlike other bacteria, grew only inside of cells. Hilleman's finding eventually led to a treatment for the disease. For his efforts, he received an award for “the student presenting the best results of research in pathology and bacteriology.” Myra Tubbs Ricketts, the widow of Hilleman's childhood hero, had endowed the award. Hilleman remembered, “You see how things tie together in your life: Howard Taylor Ricketts!”

In 1944 Maurice Hilleman came to a crossroads. He had just finished his graduate studies in Chicago. Now he was expected to take his place among the academic elite as a teacher and researcher. But Hilleman wanted to work for the pharmaceutical company E. R. Squibb in New Brunswick, New Jersey. His mentors made it clear to him that working for a pharmaceutical company wasn't an option. “I left Chicago under significant duress,” recalled Hilleman. “Because Chicago at that time was such an intellectual center of biology, no one went into industry. When you graduated from the University of Chicago, you would be announced [into the field of science]. I was not allowed to look for a job in industry.” But Hilleman had tired of academia. “What am I supposed to do? I was told that you could teach or you could do research. I said I wanted to go into industry because I'd learned enough about academia. I wanted to learn something about industrial management. I came off a farm. We had to do marketing. We had to do sales. I wanted to do something. I wanted to make things!” Hilleman's decision irked his professors. So they added one more hurdle before allowing him to graduate: a French exam. “I spent six months learning French,” he recalled. “Every day I learned ten pages of philosophic French and a hundred idioms and analogies. I passed the test.” Reluctantly, Hilleman's mentors abandoned their protests. “Now you can go into industry,” they said. At Squibb, Hilleman learned how to mass-produce influenza vaccine.

Four years later, in the late spring of 1948, he arrived at the Walter Reed Institute in Washington, D.C. His assignment at Walter Reed was to learn everything he could about influenza and to prevent the next pandemic. Confident, tall, and handsome, Hilleman commanded the respect of his research team with intellect, profanity, and humor.

Â

E

STABLISHED ON

M

AY

1, 1909,

THE

W

ALTER

R

EED

A

RMY

M

EDICAL

Research Institute supported research on any infection that could influence the outcome of wars. History supported its mission.

During Britain's occupation of India in the early 1800s, one third of its troops died of cholera. During the Crimean and Boer Wars, in the mid-and late 1800s, more British troops died of dysentery than in battle. During the First World War, typhus, a bacterial infection spread by lice, infected hundreds of thousands of Serbs and Russians. And during the Second World War, influenza killed thousands of American soldiers.

But for demonstrating how infections can change the outcome of wars, no war matched the Spanish conquest of Mexico in the sixteenth century. With an army of only four hundred men, Hernando Cortez conquered an Aztec civilization of four million. Cortez didn't defeat the Aztecs because his men were braver (the Aztecs were fierce, noble fighters) or because he was more adept at recruiting other Indian tribes to join him (allies joined Cortez only after they were sure he would win) or because he had more guns and horses (the guns were crude and the horses were of limited value). So what was it? What caused an Aztec civilization of millions to lay down its arms and wholly, unequivocally surrender to a few hundred Spanish invaders? The answer was an infection that had been circulating in Europe for centuries but had never crossed the Atlantic Ocean: smallpox. Within one year of the Spanish invasion, the smallpox plague had killed millions. The Aztecs interpreted the plague as punishment, convinced that their invaders enjoyed divine favor. “The religions, priesthoods, and way of life built around the old Indian gods could not survive such a demonstration of the superior power of the God the Spaniards worshipped,” wrote William McNeill, author of

Plagues and Peoples

. “Little wonder, then, that the Indians accepted Christianity and submitted to Spanish control so meekly. God had shown Himself on their side, and each new outbreak of infectious disease imported from Europe, and soon from Africa as well, renewed the lesson.”

Â

I

N THE LATE

1940

S TWO INSTITUTIONS MONITORED STRAINS OF

influenza virus that circulated in the world: the Walter Reed Institute and the newly formed World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland. “I was in charge of the central laboratory for the military worldwide surveillance for early detection of [pandemic] viruses,” recalled Hilleman. “And in 1957 we all [initially] missed it. The military missed it and the World Health Organization missed it.”

On April 17, 1957, while sitting in his office, Hilleman read an article in the

New York Times

titled “Hong Kong Battling Influenza Epidemic.” “I saw an article that said that there were twenty thousand people lined up being taken to the dispensaries. And children with glassy-eyed stares, tied to their mother's backs, were waiting to be seen.” Public health officials estimated that the virus had infected two hundred fifty thousand people, 10 percent of Hong Kong's population. Hilleman put down the paper: “My God,” he said, “This is the pandemic. It's here!”

The next day Hilleman cabled the army's 406th Medical General Laboratory in Zama, Japan. He asked the staff to find out what was going on in Hong Kong. A medical officer sent to investigate eventually found a navy serviceman who had been exposed to the virus in Hong Kong, gotten back on his ship, returned to Japan, and become ill. The officer asked the young man to gargle with salt water and spit into a cup, hoping to capture the virus.

The specimen reached Hilleman on May 17, 1957. For five days and nights he worked to determine whether the influenza virus circulating in Hong Kong could be a pandemic strain. Hilleman took an incubating hen's egg, cut a small window in the shell, and injected the egg with throat washings from the navy serviceman. Influenza virus grew readily in the membrane surrounding the chick embryo. He harvested the virus-containing fluid, purified it, and added sera from members of the American military, hundreds in all. No one had antibodies to the new virus. (Serum [plural ”sera”] is the fraction of blood that contains antibodies. Antibodies are proteins made by the immune system to neutralize invading viruses and bacteria.) Hilleman then tested sera from hundreds of civilians in the United Statesâagain no antibodies. He couldn't find one person whose immune system had ever confronted this particular strain of influenza virus before.

To confirm his findings, Hilleman sent the virus to the WHO, the U. S. Public Health Service, and the Commission on Influenza of the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board. Each of these organizations tested sera from adults throughout the world. Only a handful of peopleâin the Netherlands and the United Statesâhad antibodies to the virus. All were elderly men and women in their seventies and eighties who had survived the influenza pandemic of 1889â1890 that had killed six million people. The virus that had caused the 1889 pandemic had disappeared quickly and mysteriously. Now it was back. And no one had antibodies to stop it.