UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY (14 page)

Read UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

Working for the notary, Simone discovered that Rebaudengo not only conducted confidential transactions for private clients but also provided services for those involved in public policing, perhaps to cover himself in the event the authorities found out about his not entirely lawful activities. Sometimes, he explained, in order properly to convict a suspect, some documentary proof had to be presented to the judges so as to persuade them that the police allegations were not without substance. In this way, Simone encountered mysterious characters who visited the office from time to time, and were what the notary described as "gentlemen from the Department." What this Department and its representatives did was hardly difficult to guess: they were concerned with secret government business.

One of these gentlemen was Cavalier Bianco, who declared one day that he was most satisfied by the way Simone had produced a certain incontestable document. His responsibilities must have included gathering reliable information on people before they were approached, because, drawing Simone aside one day, Bianco asked whether he still went to Caffè al Bicerin and suggested meeting there for what he described as a private chat.

"My dear Avvocato Simonini," he said, "we are well aware that you were the grandson of one of His Majesty's most devoted subjects, and were therefore soundly educated. We also know that your father paid with his life for things we too consider to be just, even though he did it, shall we say, with excessive haste. We therefore confide in your loyalty and your willingness to collaborate, considering also that we have been most indulgent toward you. We could have incriminated you and Notaio Rebaudengo some time ago for your not wholly commendable activities. We know you have friends, associates, comrades in spirit, shall we say — Mazzinians, Garibaldians, Carbonari. That is natural. It would seem to be the fashion among the younger generation. But our problem is this: we do not want these young people to lose their heads, at least not until it is reasonable and helpful to do so. Our government has been concerned about the mad antics of that man Pisacane, who landed by boat on the island of Ponza several months ago waving the tricolor flag, along with another twenty-four subversives, then liberated three hundred prisoners and sailed for Sapri, thinking that the local people would be waiting to support him with arms. The more charitable say that Pisacane was a generous soul, the skeptical say he was a fool, but the truth is he was deluded. He and his supporters ended up being massacred by the scoundrels he wanted to liberate, and so you see where good intentions can lead when they take no account of the facts."

"I understand," Simone said. "But what do you want from me?"

"Well, if we need to stop these young men making mistakes, the best way is to put them behind bars for a while, accusing them of attacking the authorities, and release them when there's a real need for zealous spirits. We must therefore surprise them in some clear act of conspiracy. You surely know who their trusted leaders are. All you have to do is send a message to someone in charge, get him to call a meeting in a particular place, everyone armed from head to foot, with cockades and flags and other bits and pieces, to make them look like Carbonari bearing arms. The police arrive, arrest them, and that'll be that."

"But if I'm with them, I'll be arrested too. And if I'm not, they'd immediately realize it was I who'd betrayed them."

"Of course, my good sir. We are not so naive as not to have thought of that."

As we shall see, Bianco had planned it well. But our Simone was also an excellent strategist, and having listened carefully to the plan that was being proposed to him, he devised an extraordinary form of payment, and told Bianco what he expected from His Majesty's munificence.

"My employer, you see, committed many crimes before I became his assistant. It would be enough for me to point out two or three of these cases where sufficient documentary evidence exists, involving no one of any real importance — perhaps someone who has died in the meantime — and for me to present the evidence anonymously, through your kind mediation, to the public prosecutor. You would have enough to convict Notaio Rebaudengo for forgery of public deeds and to put him behind bars for a sufficient number of years, enough to let nature run its course — certainly not very long, given the old man's present state."

"And then?"

"And then, as soon as Notaio Rebaudengo is in prison, I will produce a contract, dated just a few days before his arrest, showing that I have completed the payment of a series of installments on the purchase of his office and am therefore the owner. As for the money, it will appear that I have paid him in full. Everyone thinks I ought to have inherited a considerable estate from my grandfather, and the only person who knows the truth is Rebaudengo himself."

"Interesting," said Bianco, "but the judge will want to know what happened to the money you are supposed to have paid him."

"Rebaudengo doesn't trust banks and keeps everything in a safe in his office. I know how to open it, of course, because he imagines that all he has to do is turn his back and, as he can't see me, he's convinced I can't see what he's doing. The police will surely open the safe somehow or other, and they'll find it empty. I could testify that Rebaudengo's offer was quite unexpected and that I myself was so astonished by the smallness of the sum he was asking that I suspected he had some reason for abandoning his business affairs. In fact, they'll find, along with the empty safe, the ashes of some mysterious documents in the fireplace, and in the drawer of his desk a letter from a hotel in Naples confirming his booking for a room. It will then be clear that Rebaudengo thought he was already being watched by the law and had decided to flee the nest, going off to enjoy his riches under Bourbon rule, where perhaps he had already sent his money."

"But if he's told about your contract in front of the judge, he'll deny it."

"Who knows what other things he'll be denying. The judge is hardly likely to believe him."

"A shrewd plan. I like you, Avvocato Simonini. You are brighter, more motivated, more decisive than Rebaudengo and, shall we say, more versatile. Very well then. You hand that group of Carbonari over to us, and then we'll deal with Rebaudengo."

The arrest of the Carbonari seemed like child's play, not least because those enthusiasts really were little more than children, and Carbonari only in their most fervent dreams. Simone, at first out of pure vanity, had been feeding the Carbonari for some time with certain bits of nonsense he had been told by Father Bergamaschi, knowing that they would take each revelation to be news he had received from his heroic father. The Jesuit had continually warned him against the plots of the Carbonari — Freemasons, Mazzinians, republicans and Jews, disguised as patriots, who hid from the police around the world by pretending to be charcoal traders, and met secretly on the pretext of carrying out their business dealings.

"All Carbonari owe allegiance to the Alta Vendita, which has forty members, most of whom, dreadful to say, are the cream of the Roman aristocracy — plus, of course, several Jews. Their leader was Nubius, a fine gentleman, as corrupt as the day is long, but who had created a position for himself in Rome that was beyond suspicion, thanks to his name and wealth. From Paris, Buonarroti, General Lafayette and Saint-Simon consulted him as if he were the oracle of Delphi. From Munich, Dresden, Berlin, Vienna and St. Petersburg, the heads of the main lodges — Tscharner, Heymann, Jacobi, Chodzko, Lieven, Mouravieff, Strauss, Pallavicini, Driesten, Bem, Bathyani, Oppenheim, Klauss and Carolus — sought his advice. Nubius remained at the helm of the highest Vendita until 1844, when someone poisoned him with Aqua Tofana. Don't imagine it was we Jesuits who did it. The author of the killing is thought to have been Mazzini, who sought, and still seeks, to become head of the Carbonari, with the help of the Jews. Nubius's successor is now Little Tiger, a Jew who, like Nubius, never stops running around stirring up enemies of Calvary. But the members and meeting place of the Alta Vendita are secret. Everything must remain unknown to the lodges that receive their direction and impetus from it. Even the forty members of the Alta Vendita have no knowledge of the origin of the orders to be given or carried out. And they say that the Jesuits are slaves to their superiors. It is the Carbonari who are slaves to a master who keeps himself well hidden, perhaps a Great Old Man who directs this underground Europe."

"All Carbonari owe allegiance to the Alta Vendita, which has forty members, most of whom, dreadful to say, are the cream of the Roman aristocracy — plus, of course, several Jews."

Simone had transformed Nubius into a personal hero, almost a male counterpart of Babette of Interlaken. And he mesmerized his companions by turning into an epic poem what Father Bergamaschi had told him in the form of a gothic tale — though concealing the small detail that Nubius was now dead.

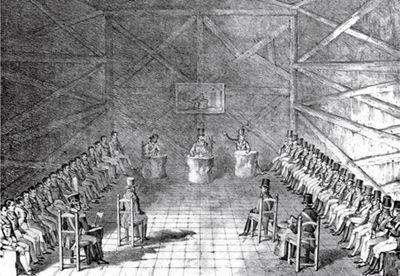

Until one day he produced a letter, which had not been difficult to fabricate, in which Nubius proclaimed an imminent insurrection across Piedmont, town by town. The group, led by Simone, would play a dangerous and exciting part. They were to meet on a particular morning in the courtyard of the Osteria del Gambero d'Oro, where they would find sabers and rifles and four cartloads of old furniture and mattresses. Thus armed, they were to make their way to the junction of via Barbaroux and build a barricade to block entry from piazza Castello. And there they should await orders.

That was more than enough to stir the hearts of the twenty or so students who met on that fateful morning in the innkeeper's courtyard and found the weapons they had been promised in several barrels. While they were looking around for the carts of furniture, without thinking to load their rifles, the courtyard was invaded by fifty or so policemen with their guns drawn. Powerless to resist, the boys surrendered and were disarmed, taken out and lined up facing the wall on either side of the entrance gate. "Come on, you rabble, hands up, silence!" an officer in plain clothes shouted with a scowl.

Although the rebels appeared to have been rounded up more or less at random, two policemen had positioned Simone at the very end of the line, right by the corner of an alleyway. At the agreedupon moment, they were called away by their sergeant and went off toward the courtyard entrance. Simone turned to his nearest companion and whispered something. Seeing that the police were a fair distance away, the two darted off around the corner and began running.

"To arms, they're escaping!" someone shouted. The two heard footsteps as they fled, and the shouts of policemen who had pursued them around the corner. Simone heard two shots. One hit his friend, though Simone was hardly concerned whether it was fatal or not. It was enough for him that the second shot was fired into the air, as agreed.

He turned into another street, then yet another. Far off, he could hear the shouts of his pursuers, who, following their orders, had taken the wrong route. Before long he was crossing piazza Castello on his way home, like any other citizen. His companions — who in the meantime had been taken away — all assumed he had escaped, and since they had been arrested together and immediately lined up facing the wall, none of the police officers could remember his face. So there was no need for him to leave Turin; he could return to work, and could even go to comfort the families of his arrested friends.

All that remained was to deal with Notaio Rebaudengo. The old man went to prison, as planned, and died of a broken heart a year later in prison, but Simonini felt no guilt about that. The score had been settled. The notary had given him a job, and Simone had been his slave for several years; the notary had ruined his grandfather, and Simone had ruined him.

This, then, was what Abbé Dalla Piccola had been describing to Simonini. And that he too felt exhausted after all these recollections was proven by the fact that his contribution to the diary stopped halfway through a sentence, as if, while he was writing, he had fallen into a state of slumber.

6