UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY (41 page)

Read UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

From this, it was clear that Hébuterne was shrewder and more intelligent than his predecessor Lagrange. He was unable to say there and then how much the Grand Orient might be able to invest in such a venture, but his reply came a few days later: "One hundred thousand francs. But on condition that it is complete and utter rubbish."

Simonini therefore had 150,000 francs for buying rubbish. If he offered Taxil only 75,000 francs, with the promise of a large circulation, he would say yes immediately, considering the difficulty he was in. And 75,000 would be left for Simonini. A fifty percent commission wasn't bad.

On whose behalf could he make the offer to Taxil? On behalf of the Vatican? Maître Fournier, the notary, didn't have the appearance of a papal plenipotentiary. Perhaps he could arrange a visit from someone like Father Bergamaschi. After all, that's the whole point of priests, so that people can convert and confess their murky pasts to them.

But when it came to murky pasts, should Simonini trust Father Bergamaschi? Taxil mustn't be left in the hands of the Jesuits. There had been atheist writers who had sold a hundred copies of a book and then fallen to their knees before the altar and recounted the story of their experience as converts, boosting their sales to two or three thousand. After all, when it came down to it, the anticlericalists counted for something among the republicans in the city, but the reactionaries who dreamt of the good old days, of king and curate, lived in the countryside and, even excluding those who couldn't read (though the priest would read to them), were legion, like demons. By keeping Father Bergamaschi out of it, Taxil could be offered a deal on his new publications and invited to sign a contract whereby whoever was collaborating with him would be entitled to ten or twenty percent on his future works.

In 1884 Taxil had dealt the ultimate blow to the feelings of good Catholics by publishing

The Secret Loves of Pius IX,

defaming a pope now dead. In the same year the reigning pope, Leo XIII, published his encyclical

Humanum Genus,

which was a "condemnation of the philosophical and moral relativism of Freemasonry." And in the same way as he had railed against the monstrous errors of socialists and communists in his encyclical

Quod Apostolici Muneris,

this time he directed his attack at the doctrines of Freemasonry, exposing the secrets that made its followers captives and prone to every kind of crime, since "this continual pretense and desire to remain hidden, this binding of men, like vile slaves, to the arbitrary will of others, and to abuse them as blind instruments for any enterprise, however evil it be, and to arm their right hands for bloodshed after securing impunity for the crime, are excesses from which nature recoils." Not to mention the naturalism and relativism of Freemasonry's doctrines, which made human reason the sole judge of everything. And it was perfectly clear what the results would be: the pope stripped of his temporal power, the intention to annihilate the Church, marriage made into a simple civil contract, the education of children no longer carried out by priests but by lay teachers, and the teaching that "all men have the same rights, and are in every respect of equal and like condition; that every man is, by nature, independent; that no one has the right to command another; that it is tyranny to require men to obey any authority other than that which emanates from themselves." So for the Freemasons "the origin of all civil rights and duties is in the people, or in the state," and the state could only be godless.

It was obvious that "once the fear of God and reverence for divine laws is taken away, the authority of rulers trampled upon, sedition permitted and approved, and the popular passions urged on to lawlessness, with no restraint save that of punishment, revolution and universal subversion will necessarily follow . . . which is the deliberate plan and open purpose of many associations of communists and socialists: to such intentions the Masonic sect cannot properly describe itself as hostile."

News of Taxil's conversion had to break as soon as possible.

At this point Simonini's diary becomes confused. It seemed he could no longer remember how Taxil was converted, or by whom. It was as if his memory were leaping ahead, allowing him to remember only that Taxil, in just a few years, had become a Catholic voice against Freemasonry. After proclaiming,

urbi et orbi,

his return to the bosom of the Church, he published

Les frères troispoints

(the three points being those of the thirty-third Masonic degree),

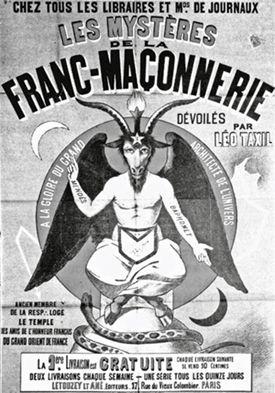

Les mystères de la Franc-Maçonnerie

(with dramatic illustrations of satanic invocations and hideous rites) and immediately afterward

Les soeurs Maçonnes,

which described the (hitherto unknown) female lodges — and a year later

La Franc-Maçonnerie dévoilée,

followed by

La France Maçonnique.

From these first books the description of an initiation was enough to make readers shudder. Taxil had been summoned to attend the Masonic lodge at eight o'clock one evening, and was met at the door by a brother. At eight-thirty he was shut inside the Chamber of Reflection, a small closet decorated with black walls, death's heads and crossbones and inscriptions such as, "If vain curiosity brings you here, depart now!" All of a sudden the gaslight flame dimmed, a false panel slid back along grooves hidden in the wall, and Taxil looked down into an underground chamber lit with grave lamps. A freshly cut human head lay on a block from which trickled blood, and as he recoiled in horror, a voice that seemed to come out of the wall cried: "Tremble, O profane one! You see before you the head of a false brother who revealed our secrets!"

It was, of course, a trick, observed Taxil, and the head must have been that of a stooge whose body was hidden in the empty cavity of the block. The wicks of the lamps had been soaked in camphorated alcohol mixed with coarse cooking salt, known by fairground conjurers as the "infernal blend," which emits a greenish light and gives a cadaverous appearance to the face of the person pretending to be beheaded. But he had heard of other initiations where walls were made with frosted mirrors onto which, as soon as the flame of the gas jet was lowered, a magic lantern made moving, ghost-like figures appear, and masked men who surrounded a figure in chains and rained dagger blows upon him. This all goes to show what shameful means were used by the lodge to exert control over impressionable aspirants.

He published

Les frères trois-points

(the three points being

those of the thirty-third Masonic degree),

Les mystères

de la Franc-Maçonnerie

(with dramatic illustrations

of satanic invocations and hideous rites) . . .

After this, a so-called Brother Terrible prepared the profane, removing his hat, coat and right shoe, rolling up his right trouser leg above his knee, exposing his arm and chest on the side of his heart, blindfolding him and turning him around several times. After making him climb up and down various steps, the Brother Terrible took him to the Hall of the Lost Steps. A door opened, and a Brother Expert, using an instrument consisting of large clashing springs, simulated the sound of enormous chains. The postulant was taken into a room where the Expert held the point of a sword to his bare chest and the Master asked, "Profane, what do you feel at your chest? What do you have on your eyes?" The aspiring Mason had to reply, "A thick blindfold covers my eyes, and I feel the point of a weapon at my chest." And the Master: "This metal, sir, always raised to punish disobedience, is the symbol of remorse that would strike your heart if, to your disgrace, you should become a traitor to the society you wish to enter; and the blindfold over your eyes is the symbol of the blindness of the man who was ruled by his passions and immersed in ignorance and superstition."

Then someone took hold of the aspiring Mason, turned him around several times until he began to feel dizzy, then pushed him in front of a large screen made of several layers of thick paper, similar to the hoops through which circus horses jump. At the command for him to enter the cavern, the poor fellow was shoved with great force against the screen, the paper broke, and he fell onto a mattress positioned on the other side.

Then there was the "everlasting staircase," which was actually a treadmill, where the blindfolded aspirant found there was always another step to climb, and each step lowered as he climbed it. Thus he continued to climb for half an hour without knowing what height he had reached, though he was still at the same level as when he started.

They also pretended to subject the apprentice to bloodletting and baptism by fire. For the blood, a Brother Surgeon bound his arm and pricked it fairly forcefully with the point of a toothpick, and another brother dripped a tiny amount of warm water over the postulant's arm so he thought it was his blood that was flowing. For the trial of the red-hot iron, one of the Experts rubbed a part of the aspirant's body with a dry cloth and then placed a piece of ice on it, or the hot part of a candle that had just been blown out, or the base of a liqueur glass heated with burning paper. Finally the Master told the aspirant about the secret signs and special mottoes used by the brothers to recognize each other.

Simonini now recalled these works of Taxil's, not as an instigator but as a reader. Nonetheless, he remembered that before each new work of Taxil's appeared, he would go (having therefore read it in advance) and describe its contents to Osman Bey as if they were extraordinary revelations. It was true that on the following occasion Osman Bey would point out that everything Simonini had told him on the previous occasion had then appeared in a book by Taxil. To this it was easy for Simonini to reply that, yes, Taxil was his informer, and it was hardly his fault that, after having revealed Masonic secrets to him, Taxil had sought financial gain by publishing them in a book. Otherwise Simonini would have had to pay to stop him from publishing his experiences — and in saying this, he fixed Osman Bey with an eloquent stare. But Osman replied that money spent on persuading a chatterbox to keep quiet was money wasted. Why should Taxil be made to hold his tongue about the very secrets he had just revealed? And, understandably suspicious, Osman offered Simonini no revelation in exchange concerning what he had learned about the Alliance Israélite.

At the command for him to enter the cavern, the poor fellow was shoved with great force against the screen, the paper broke, and he fell onto a mattress positioned on the other side.

At which point Simonini stopped passing information to him. But as he wrote in his diary, Simonini reflected on this problem: "Why do I remember giving Osman Bey information I'd received from Taxil, but nothing about my dealings with Taxil?"

Good question. If he remembered everything, he wouldn't be here writing down what he was gradually piecing together.

Quelle histoire!

With that sage comment, Simonini went to bed, reawakening on what he thought to be the following day, bathed in sweat as if after a night of bad dreams and indigestion. But returning to his desk, he discovered he had awoken, not the next day, but two days later. During not one but two nights of restless sleep, Abbé Dalla Piccola, not content to dump corpses in Simonini's own personal sewer, had made his inevitable appearance, describing events about which the captain clearly knew nothing.

22

THE DEVIL IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

14th April 1897

Dear Captain Simonini,

Once again, where your ideas are confused, my memories are much clearer.

I remember meeting Monsieur Hébuterne and then Father Bergamaschi as if it were today. I go on your behalf to receive the money I had to give (or should have given) to Léo Taxil. Then I visit Taxil, this time on behalf of Maître Fournier, the notary.

"Monsieur Taxil," I say, "I have no wish to use my clerical attire as a ploy to persuade you to recognize our Lord Jesus Christ, whom you deride. Whether or not you go to hell is a matter of supreme indifference to me. I am not here to offer you any promise of eternal life, but rather to inform you that a series of publications condemning the crimes of Freemasonry would find a readership of right-thinking people, which I have no hesitation in describing as vast. Perhaps you have no idea what it is worth for a book to have the support of every monastery, every parish church, every diocese, not just in France but far away throughout the world. As proof that I am not here to convert you but to help you make money, I will tell you right away what my modest proposals are. All you must do is sign papers assuring me (or rather, the religious congregation I represent) twenty percent of your future rights, and I'll introduce you to some one who knows more than you about the mysteries of Freemasonry."