UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY (9 page)

Read UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

"This," my grandfather concluded, "was what I told Barruel. Perhaps I exaggerated a little, saying that I had learned from all of them what, in fact, I had heard from one man alone, but I was and still am convinced the old man was telling the truth. And that is what I wrote, if you'll let me finish reading."

And my grandfather resumed:

"These, sir, are the perfidious plans of the Hebrew nation, which I heard with my own ears. It would therefore be most desirable that a persuasive and distinguished pen such as yours should open the eyes of the aforesaid governments, and direct them to return these people to the abjection that is properly theirs, and in which our more prudent and judicious forefathers had always endeavored to keep them. This, sir, I invite you to do on my behalf, asking you to forgive an Italian, a soldier, for any errors you may find in this letter. I wish you by God's hand the most bounteous reward for the illuminating writings you have bestowed on His Church, and that He may inspire, in those who read them, the highest and most profound esteem for you, to whom I am honored to be, sir, your most humble and obedient servant, Giovanni Battista Simonini."

At this point, on each occasion, my grandfather returned the letter to the chest and I asked, "And what did Abbé Barruel say?"

"He did not deign to reply. But I had some good friends in the Roman Curia, and so discovered that this coward was afraid that if such truths were to spread, it would trigger a massacre of the Jews, which he did not wish to provoke since he believed there were innocent people among them. What is more, when Napoleon decided to meet representatives of the Grand Sanhedrin to obtain their support for his ambitions, certain threats from the French Jews of the time must have had an effect — and someone must have informed the abbé that it was better not to stir up trouble. But at the same time Barruel felt unable to remain silent, and this is why he sent my original letter to the Supreme PontiffPius VII, and copies to a large number of bishops. Nor did the matter rest there, because he also conveyed the letter to Cardinal Fesch, then primate of the Gauls, so he could inform Napoleon. And he did the same with the chief of police in Paris. And the Paris police, I am told, carried out an investigation at the Roman Curia to find out whether I was a reliable witness. And, by the devil, I was — the cardinals could hardly deny it! In short, Barruel was attacking from undercover: he did not want to stir up any more trouble than his book had already caused, but while appearing silent he was sending my revelations halfway around the world. You should know that Barruel was educated by the Jesuits until Louis XV drove them out of France, and then took orders as a lay priest, except that he became a Jesuit once again when Pius VII restored full rights to the order. Now, as you know, I am a fervent Catholic and profess the highest respect for any man of the cloth, but a Jesuit is surely always a Jesuit — he says one thing and does another, does one thing and says another — and Barruel behaved no differently."

My grandfather chuckled, spluttering spit through his few remaining teeth, amused by that sulfurous impertinence of his. "So there it is, my dear Simonino. I am old, it is not for me to be the lone voice in the wilderness. If they didn't want to listen to me, they will answer for it before God Almighty, but I pass the flame of witness on to you young people, now that those most damnable Jews are becoming increasingly powerful and our cowardly sovereign Carlo Alberto is proving ever more indulgent toward them. But he will be overthrown by their conspiracy."

"Are they also plotting here in Turin?" I asked.

My grandfather looked around him, as if someone were listening to his words, while the shadows of dusk darkened the room. "Here and everywhere else," he said. "They are an accursed race, and their Talmud says — as anyone who can read it will confirm — that the Jews must curse the Christians three times a day and ask God that they be exterminated and destroyed, and if one of them meets a Christian on a precipice he must push him over. You know why you are called Simonino? I wanted your parents to baptize you in memory of Saint Simonino, a child martyr who, back in the fifteenth century near Trent, was kidnapped by Jews, who killed him and chopped him up to use his blood in their rituals."

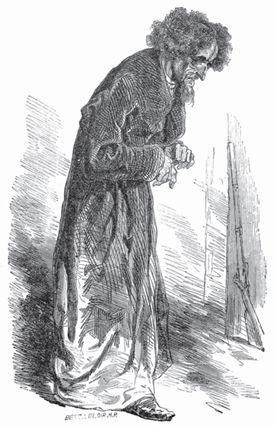

"If you don't behave yourself and go straight to sleep, the horrible Mordechai will come visit you tonight." That is how my grandfather threatens me. And it's hard to get to sleep in my small attic room, straining my ear each time the old house creaks, almost hearing the terrible old man's footsteps on the wooden staircase, coming to get me, to drag me offto his infernal den, to feed me unleavened bread made with the blood of infant martyrs. Confusing this with other stories I hear from Mamma Teresa, the old servant who had been my father's wet nurse and still shuffles about the house, I imagine Mordechai dribbling lubriciously, muttering, "Fee-fi-fo-fum, I smell the blood of a Christian boy."

I am almost fourteen, and several times I've been tempted to go into the ghetto, which now oozes out beyond its old confines, since many restrictions are to be removed in Piedmont. Perhaps I'll come across a few Jews while I wander almost to the frontier of that forbidden world, but I've heard it said that many have abandoned their centuries-old ways. "They disguise themselves," my grandfather says, "they disguise themselves, pass us in the street without us even realizing." While wandering its limits, I meet a girl with black hair who crosses piazza Carlina each morning carrying a basket covered with a cloth to a nearby shop. Fiery gaze, velvet eyes, dark complexion . . . Impossible that she's a Jewess, that those men my grandfather has described, with rapacious features and venomous eyes, could produce women like her. And yet she can only have come from the ghetto.

This is the first time I have looked at a woman other than Mamma Teresa. I go back and forth each morning and my heart begins to pound as soon as I see her in the distance. On those mornings when I do not see her, I wander around the square as if I'm trying to find an escape route, and I reject each one of them, and I'm still there when my grandfather expects me back home, sitting furious at the table, nibbling crumbs of bread.

One morning I dare to stop the girl and, eyes lowered, ask her if I can help carry her basket. She replies haughtily, in dialect, that she can manage perfectly well by herself. But she doesn't call me

monssü

, but

gagnu

, boy. I've stopped looking out for her. I haven't seen her since. I've been humiliated by a daughter of Zion. Is it perhaps because I'm fat? This, in fact, marks the beginning of my war against the daughters of Eve.

Throughout my childhood, my grandfather refused to send me to the government school because he said the teachers were all Carbonari and republicans. I spent all those years alone at home, watching resentfully for hours as the other children played by the river, as if they were taking something away from me that was mine. The rest of the time I spent shut up in a room studying with a Jesuit father whom my grandfather always chose, according to my age, from among the black crows who flocked about the area. I hated the teacher of the moment, not just because his way of teaching was by rapping my knuckles, but also because my father (the few times he spent distractedly with me) had instilled in me a hatred of priests.

"But my teachers are not priests, they are Jesuit fathers," I used to say.

"Even worse," retorted my father. "Never trust Jesuits. Do you know what one holy priest has written (a priest, I say, and not a Mason or a Carbonaro or one of Satan's Illuminati — as they think I am — but a priest of saintly kindness, Father Gioberti)? It is Jesuitism that undermines, torments, afflicts, vilifies, persecutes, destroys men of free spirit; it is Jesuitism that drives good and valiant men out of public positions and replaces them with others who are base and contemptible; it is Jesuitism that slackens, obstructs, torments, harasses, confuses, weakens, corrupts public and private education in a thousand ways, which sows bitterness, mistrust, animosity, hatred, unrest, open and covert discord among individuals, families, classes, states, governments and peoples; it is Jesuitism that weakens minds, tames hearts and desires, reducing them to a state of sloth, that debilitates young people through feeble discipline, that corrupts adults through acquiescent, hypocritical morality, that combats, weakens and stifles friendship, domestic relationships, filial piety and the sacred love most people feel for their country . . . No sect in the world is so gutless (he said), so hard and ruthless when its own interests are at stake, as the Company of Jesus. Behind that soothing and alluring face, those sweet and honeyed words, that kind and most affable manner, the Jesuit who responds worthily to the discipline of the order and the instructions of his superiors has a heart of iron, impenetrable to higher feelings and nobler sentiments. He firmly puts into practice Machiavelli's precept that where the well-being of the state is in question, no consideration should be given to right or wrong, to compassion or cruelty. And for this reason they are taught as young seminarians not to cultivate family affections, not to have friends, but to be ready to reveal to their superiors every slightest shortcoming in even their closest companion, to control every impulse of the heart and to offer absolute obedience,

perinde ac cadaver

. Gioberti said that whereas the Indian Phansigars, or stranglers, sacrifice the bodies of their enemies to their deity, killing them with a garrotte or a knife, the Jesuits of Italy kill the soul with their tongues, like reptiles, or with their pens.

. . . almost hearing the terrible old man's footsteps on the wooden staircase, coming to get me, to drag me offto his infernal den, to feed me unleavened bread made with the blood of infant martyrs.

"I have always been amused," my father concluded, "that Gioberti took some of these ideas secondhand from

The Wandering Jew

, a novel by Eugène Sue, published the year before. " My father. The black sheep of the family. My grandfather said he was mixed up with the Carbonari, but when I mentioned this to my father, he told me quietly not to listen to such ramblings. He avoided talking to me about his own ideals, perhaps out of shame, or respect for his father's views, or reticence toward me. But it was enough for me to overhear my grandfather in conversation with his Jesuit fathers, or to catch the gossip between Mamma Teresa and the caretaker, to realize my father was among those who not only approved of the Revolution and of Napoleon, but talked about an Italy that would shake off the power of the Austrian empire, the Bourbons and the pope, to become a nation (a word never to be uttered in my grandfather's presence).